The fleeting pulse of reality

Pla called Life Embitters 'narrative literature', a book combining a youth's passion to understand the world and a revised mature take on the follies of human behaviour

This new translation of Josep Pla is an unclassifiable, happy mix of stories, memoir, essays, anecdotes and travel pieces, all brought together by Pla's wonderfully direct, ironic style. The basis of his writing is observation of detail. As he wrote in The Gray Notebook: “The drama of literature never changes. It is much more difficult to describe than to opine. In view of which, everyone prefers to opine.”

Boarding-houses

Most of these pieces take place in boarding-houses: in Barcelona, Madrid, Paris, Leeds (wet and depressing, but the narrator loves it), Florence, Rome, Estoril, London, Berlin (home to three dark, long stories of illness and death), Marseille, Ostend and Calais (a spy story); and three on trains, which is presented as a sort of boarding-house on wheels, where you may get to know someone closely for a short time, then never see them ever again.

In the different corridors of lodgings and dining-rooms, Pla gets to meet his lonely, single and poor fellow-residents, their lives concealed behind the locked doors of their rooms. They are sordid rooms that are seething with passion and intrigue. Pla reports the anecdotes and gossip (walls are thin and morals are low). He also befriends some residents and tells us their stories. He sits apart: the man in the café with a cigarette and glass of wine who watches everyone else.

“We would feel very happy if we succeeded in capturing the fleeting pulse of the reality of things,” Pla writes in the chapter, 'Memories of Florence'. This he achieves time and again, often with memorable descriptions. Here's an example: note his luxuriant yet precise use of adjectives, a usage knocked out of so many English-language writers by the emphasis of Pla's contemporary Hemingway on understatement: “Maria Souza… was an extraordinarily fine brunette, with large ecstatic pale-blue eyes, moist lips, and pink luminous skin. She was tall and buxom” (p.371).

Often Pla's descriptions are similar to what another contemporary, Christopher Isherwood, achieved as a 'camera', the fly on the wall observing acutely. Pla, though, does more. He is never a neutral camera: always present is his witty voice. The sentence about Maria Souza quoted above continues: “However, what most surprised me about that woman was…” Pla expresses opinions, a point of view.

Boundless vanity

And he generalises, too. The lodgers are divided into payers and non-payers... A man who enters a casino ages 10 years...the English are more open-minded than the French. And, what's more, these general thoughts are not just individual sentences, but often long riffs: on the character of cats, on gambling, on Catalans abroad, on Italian painting and, inevitably, on the nature of boarding-houses and their landladies. These opinions fill out the observed detail, so that readers are moved between the capture of the 'fleeting pulse' and a wider view of the world.

Pla's portraits are sharp, but not cruel: in part, because he does not except himself. He (the narrator, often but not always to be confused with Pla) tells us that he himself is ugly and myopic. He discovers the “preposterous airs people gave themselves”. He starts “to become aware of the significance and boundless range of human vanity.” And, despite the melancholy Pla expresses in his title and the sad unrooted lives he describes, the book's portraits are often very funny.

In his piece on Italian painting, Pla urges his readers to throw away the “pamphlets that only distort your vision – however handy or abstruse they might be… Set out to see things firsthand, be curious: that's the way to travel.” This is what he did. Combining general comment and the immediacy of close observation, he helps us see the world afresh.

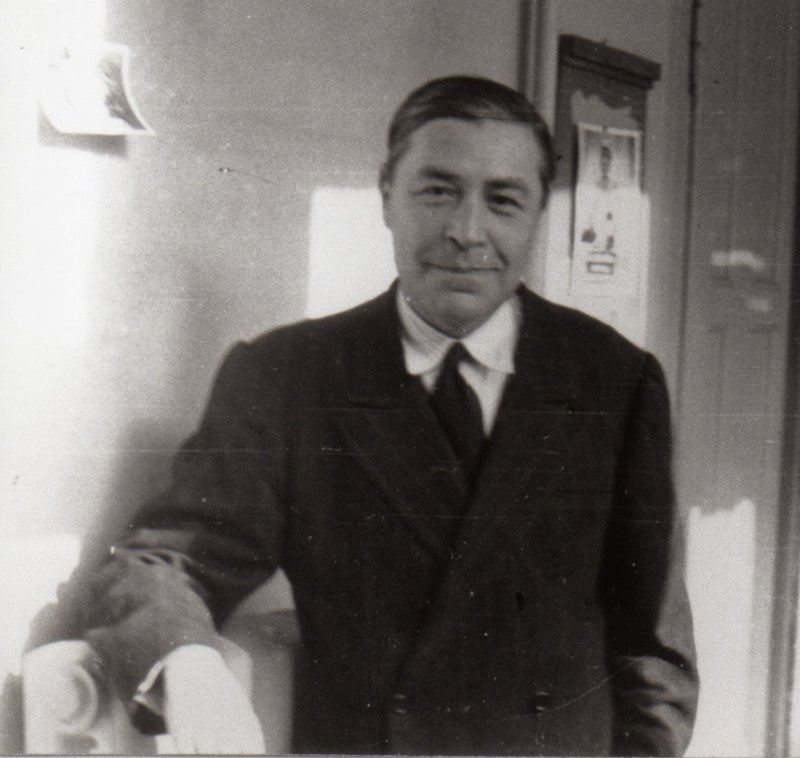

Josep Pla (1897-1981)

Josep Pla is one of Europe's major twentieth-century writers. A liberal journalist in the 1920s and '30s, he reported from all over the continent for Catalan newspapers. This career was halted by the 1936 revolution. After the victory of Franco in 1939, the Catalan language was banned in the dictator's murderous attempt to create a uniform, centralised Catholic Spain. By the 1960s it began to be possible to publish in Catalan again. In 1966 and 1967 Pla published his two masterpieces, The Gray Notebook (El quadern gris) and Life Embitters (La vida amarga).

Pla and other Catalan-language writers were effectively lost to translation during the Franco years. Lamentably, after the dictatorship ended in the late '70s, foreign publishers were not democratic enough to notice this fine literature and compensate for the years of suppression. Only in the last few years have English-language readers been able to read translations from Catalan - many through the enthusiasm of Peter Bush, who does another fine job of translating the long and complex Life Embitters.

A quibble: Pla was a much more interesting person than this publisher makes out. The blurb glosses over the less seemly aspects of his character, but these contribute to his being so contradictory and profound a writer. In 1936 he left Catalonia: he came from a family of minor landowners and, hostile to the anarchist revolution, fled. He had connections with Falangists and the leader of the Catalan right, Francesc Cambó, who supported and financed the military revolt. In exile, he spied for Franco on shipping out of Marseille (city featured brilliantly in Life Embitters) and re-entered Barcelona with Franco's victorious army in January 1939.

Rapidly disappointed by Franco's anti-Catalan crusade, Pla became an 'internal exile' at his family's Mas Llofriu near Palafrugell. During World War II, he on occasion spied on shipping for the allies. Denied a passport until the mid-50s, he resorted to writing travel books in Spanish. Travel books ran less risk with the censors. Copious author of dozens of books and articles, in old age he sank into alcoholism and depression.

After Pla's death, the Pujol governments of the 1980s and '90s exalted him as the archetypal Catalan writer (doubtless, Mercè Rodoreda was too feminist for them). They created an image of Pla as the canny old peasant, surviving by stealth and stamina the dictatorship in his Empordà farmhouse. Pla was indeed conservative and cunning, but this picture of the writer distorts the breadth of his literary achievement. He is a complex modern master, not to be assimilated to one perspective. Forget about Pujol and make sure you read him.