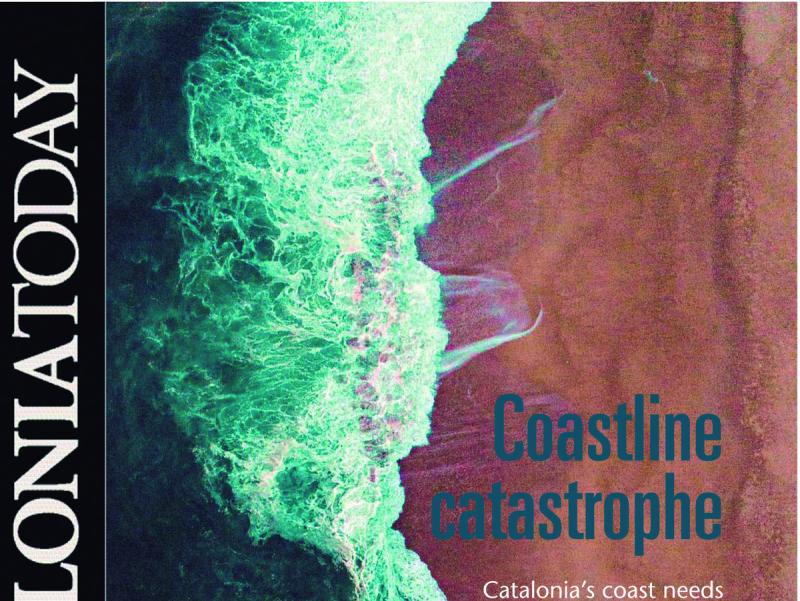

Coastline at the limit

The Catalan coast is overbuilt and densely populated, while the long-term effects of human intervention have altered the dynamics of its beaches. Action is no longer merely advisable, but a necessity

70 kilometres:

the approximate length of the Catalan coast, from Portbou to Cases d’Alcanar.43% of the population

is concentrated in coastal municipalities, although they represent only 6.7% of the country’s surface area.70 towns have coastlines.

They are located in the counties of Alt and Baix Empordà, La Selva, Maresme, Barcelonès, Baix Llobregat, Garraf, Baix Penedès, Tarragonès, Baix Camp, Baix Ebre and Montsià.From Portbou to Cases d’Alcanar, Catalonia’s coastline is some 580 km long, or 6.7% of the country’s total surface area. It is also home to 12 of Catalonia’s 42 counties and almost half of the country’s population (43.3%). These are figures from the report ’Un litoral al límit’ (Coastline at the limit),compiled by the Advisory Council for the Sustainable Development of Catalonia (CADS). The document concludes that pressure on the Catalan coast is unsustainable and that immediate action is needed.

The diagnosis

Apart from the temporary wounds inflicted by storms like Glòria (January 2020) or rises in sea levels that cyclically affect vulnerable coastal areas such as the Ebre Delta, recent figures show that beaches have regressed significantly in the coast’s more urbanised areas. In Montgat, for example, the average beach regression rate is 7.5 m per year, a figure that reaches 9.8 m in Badalona.

The Mediterranean sea is rising at a rate of 4 mm per year, says CADS, and in Estartit, for example, it has risen almost 10 centimetres over the past 30 years. Only 20% of the Catalan coast has enough space to accommodate this retreat in the face of rising sea levels, which global projections indicate could be as much as a metre by the end of the century. There is a lack of data on deltas, but they are also regressing due to erosion and subsidence. The Ebre Delta coast is receding more than 10 metres per year, and the Llobregat Delta has retreated almost a kilometre in the past century. The picture is not rosy, but what makes the figures even more alarming is that 59% of the first 100 metres of the coast is urbanised, with 120,000 new planned homes on hold while the Catalan government conducts a review of unsustainable land.

On its list of critical points, CADS warns about the survival of coastal habitats: 70% of species and 50% of the coastal and marine system habitats catalogued by the EU-sponsored Habitats Directive are in a poor state of conservation, with only 17% in a favourable state.

The report stresses that the impact of climate change on the coast will also have an effect on coastal infrastructure, whether transport (such as the R1 Rodalies railway line), energy, sanitation or communications. Ports are also located in areas vulnerable to climate change. Storm Glòria, for example, caused damage with an estimated cost of more than 75 million euros in repairs to ports, beaches and promenades.

The solutions

There is no magic solution and the study argues that what is needed most is a complete rethink of how to make the coast more resistant. The report’s authors applaud the passing of Law 8/2020 on the protection and management of the coast and the land review being carried out by the Catalan authorities. Yet they also point to other tools that they argue would aid the climatic adaptation of the Catalan coast. They talk about the creation of a Coastal Conservatory as an instrument to allow the acquisition and protection of coastal areas, and the promotion of specific plans to restore and conserve the coast or manage its tourism. They also propose a programme of urgent action to adapt the current infrastructure to climate change and plans for the transformation of urban areas, which they argue should be renaturalised.

Current regulation

While the state continues to have the say over issues of general interest on the Catalan coast, the Catalan government extended its own powers with the passing of the Coastal Protection and Management Act in July 2020. Known as Law 8/2020, the new regulations require activities on the coast to be planned, aim to preserve and recover coastal areas, including their ecosystems and landscapes, prevent and reduce the effects of climate change, regulate access to beaches and ensure coherence between public and private initiatives.

Xavier Berga, head of Coordination of Coastal, Rural Environment and Mountain Actions, stresses that it is a very ambitious law that “has to become the road map for what must happen on the Catalan coast in the coming years.” The hope is that local authorities will use general parameters to manage their own plans for the use of beaches and the coast: “Apart from the plans for the Maresme and the Ebre Delta, there is no coherent planning from the state and we want to fill this gap,” Berga says, who adds that the document is not binding.

The law also provides for the creation of the Coastal Conservatory. Berga admits there are delays but says it is inevitable. “We want the creation and operation of this body to be very participatory, both when choosing which properties to acquire and when deciding who should manage them,” he says. Movements like SOS Costa Brava have complained about the delays. “It’s not what we want,” says Sergi Nuss, who chairs the federation of over 20 organisations fighting to defend the Costa Brava’s landscape and stop urban speculation. If the conservatory were already operational, then a private individual’s purchase of the land of the former US military base Loran in the Montgrí Natural Park could have been prevented, Nuss says.

Land review

There is also the task of reviewing urban planning in Catalonia, which in January 2021 led to the approval of the urban master plan (PDU) for the review of unsustainable coastal lands in Girona. Known as the Costa Brava Protection Plan, the review served to declassify land and prevent the construction of 15,000 homes. Agustí Serra of the General Directorate of Spatial Planning and Urbanism talks about an unprecedented task that began in 2015, when it was decided to review the legacy of a very expansive urban planning model. First a review was carried out in the High Pyrenees, preventing the building of 8,500 homes, and then came the Girona coastline: “We’re not eliminating any buildings. Although it’s a very efficient and very ambitious review, there are some limitations, and what has been done is a task of fine surgery,” says Serra.

SOS Costa Brava celebrates the approval of the PDU, although they consider it insufficient, because it still foresees the potential building of 30,000 homes. “Now is the time for local authorities to act, and the sooner they review their urban plans the better. We hope they will be brave and revise conservatively,” says Nuss, who regrets cases such as the one in Cadaqués, where the local council’s review of its urban plans to bring them into line with the PDU led them to keep plans to build up to 800 new homes, which Nuss says does nothing more than “disfigure the pearl of the Costa Brava”.

With the exception of the Barcelona coastline, a separate case, the same review of unsustainable land is underway in the 41 coastal municipalities. The advance draft was approved in September and the document is now being drawn up to review 335 specific areas in 30 municipalities where, under current planning laws, 110,000 homes could be built. While waiting for the document to be published, building licences have been suspended in 236 undeveloped areas that have already been found to be unsustainable.

Raw material of tourism

To preserve the coast, huge amounts of sand are needed, known as the raw material of tourism. There are no beaches without sand, and regularly trucking it in is no long-term solution. The CADS report says that between 2002 and 2010, in an attempt to stop the effects of coastal degradation of beaches, approximately 775,000 m³ of sand per year were brought in, mostly to the beaches of Barcelona. Despite the money spent, the problem persists and the authors argue for a change in the management of beaches to make them more resilient without having to rely on these contributions of extra sand. Xisco Roig is an expert in the field. A doctor of geography and geology, he is a senior voice in beach management and especially in the recovery and management of dune systems. “Beaches will never go away,” he says, adding that this does not mean that we can continue doing what we have thus far - “which is nothing since the 1950s” - and continue using them as just leisure areas.

“The beach is the most dynamic and mobile system on the planet, even more than a river, which is a confined channel. The problem is that beaches have been designated as a summer service and not as a dynamic all-year-round system,” explains Roig, who is in charge of beach management reports, applying sustainability criteria, and, where possible, dune recovery. “I propose nature-based measures with minimal intervention. Soft measures that help natural regeneration,” he says.

The measures he proposes take more time than artificial regeneration, but are about reversing the interventionist actions that have broken the natural dynamics of the beach system over the years. “We’re treating beaches like public squares, mechanically cleaning them, which is absurd and very harmful,” says Roig, who has worked in the Balearic Islands, the Caribbean, Valencia and here in Catalonia. “My goal is to manage beaches properly and make them more resilient,” he says.

There is plenty of work to be done by everyone. But there is also work to undo what has gone wrong in the past. The head of the Montgrí, Medes Islands and Baix Ter Natural Park, Ramon Alturo, is clear about the need for action to preserve the coastline: “It is necessary to remove certain elements of human action, because if nothing is done, in 15 or 20 years it will be flooded.”

feature Environment

feature environment

Advising the government Unstoppable regression

In 1998, a parliamentary request led to a new environmental advisory council in Catalonia. CADS (the Advisory Council for Sustainable Development) is a strategic advisory body to the Catalan government in the area of sustainability based on consultation with renowned experts. The body, which reports to the Department of Climate Action, Food and Rural Agenda, prepared a first report on the state of the marine environment in 2019: A sea of change, which recommended sustainable management of the marine and coastal environment. The continuation of this work is the Coastline at the limit report, which was presented to the government in September and recommends integrated management of the Catalan coast.

In the Maresme area north of Barcelona, the problem is endemic. The beaches are in decline and the fact that they are confined by port structures and railway tracks limits any room for manoeuvre. The only action currently being taken is spending millions of euros on extra sand, which just ends up being washed away by the sea. Xisco Roig says that 1,800,000 m³ of sand were dumped on Catalan beaches In the 1990s. “Artificial regeneration has a maximum shelf life of 30 years, and then it starts to decline,” he explains. In 2015, the state authorities approved a strategic plan for Maresme that provided for 30 projects based on the artificial regeneration of the beaches. The first one, in the Maresme town of Premià, is still pending.

La Pletera: the de-urbanised urban development

It was supposed to become a kind of garden city on the Costa Brava seafront between Estartit and Pals, with a capacity for 12,700 inhabitants. The revision of the original general plan carried out by the first democratic local authorities downsized the proposal to 655 homes on the seafront for 3,000 people. The first residential block was built and the promenade and streets were redeveloped for future development. But that is far as the project ever went.

Today, far from what was originally planned, La Pletera has become a seven-kilometre-long natural beach with dunes that help protect wetland areas home to endangered fish and bird species, such as the Spanish toothcarp and the Kentish plover.

This re-naturalisation of this urban area only came about thanks to the economic crisis that followed the 1992 Olympic Games and the subsequent halt to building work. It is also down to the courage shown by the Torroella de Montgrí town council, which stopped the project and promoted de-urbanisation of the area under the European Union’s LIFE environmental programme, which ran between 2014 and 2018. Since then, the area has become integrated into the Montgrí, Medes Islands and Baix Ter Natural Park, which has continued to work on the restoration and recovery of the dunes.

“With the restoration of the dunes and the habitats that go with them, we have gained more than a metre of height on the beach in just five years,” explains Ramon Alturo, director of the natural park. Although there has been a 12-centimetre rise in the sea level since the 1970s, drone surveys conducted since 2016 show that the beach is recovering, while the work done to restore the dune system has earned the park the Climate Change Award from EUROPARC, the European network of natural parks.

Apart from the La Pletera urban development, in the southern part of the natural park, in the municipality of Pals, is still to be found what is left of Radio Liberty. The facilities that used to host the United States government’s anti-communist propaganda radio station that broadcast during the Cold War are in a dilapidated condition. The facilities are state-owned and a demolition order for them already exists, but the park authorities are concerned about preserving the natural environment that surrounds them. “Because it has been closed off, a very unique dune habitat has developed around it that should be preserved,” says Alturo.