The danger of microplastics

Growing scientific evidence shows how microplastics are harming not only the environment but also human health. A recent study shows how they alter our gut microbiota

P plastics have colonised the planet thanks to their resilience and ability to disperse. Environmentalists have long warned about the impact of plastics on the environment, but they also affect human health, in the form of microscopic particles that get into our bodies.

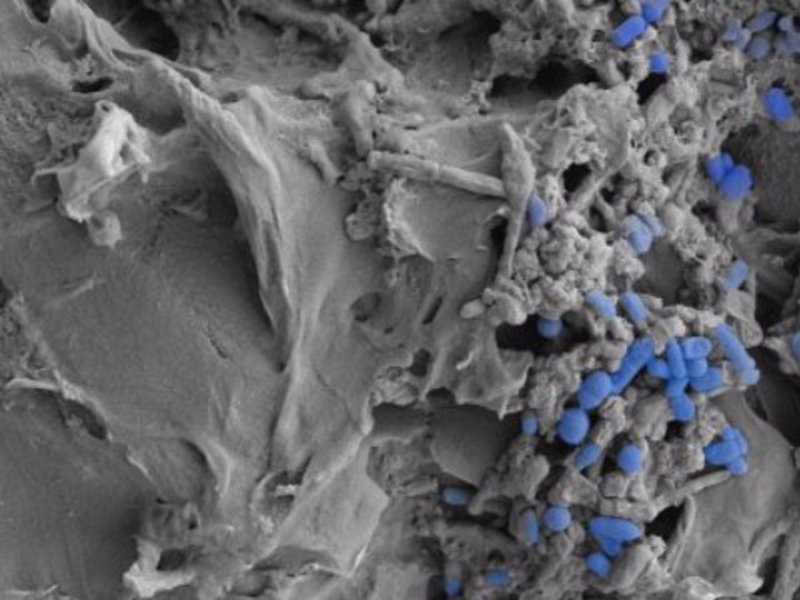

Researchers from Spain’s National Research Council (CSIC), have recently discovered that taking in microplastics through food reduces and alters the bacterial diversity of the gut microbiota. Also called intestinal flora, the gut microbiota is made up of various bacteria and microorganisms that are beneficial for our health. Some experts even consider gut microbiota to be another organ because of its importance for our immune systems.

The study published in Scientific Reports shows that ingesting PET (polyethylene terephthalate) microplastics – mainly used to make water bottles – decreases the abundance of beneficial bacteria in the intestines while causing microbial groups related to the appearance of diseases to increase. Alterations in the human microbiota have been linked to conditions as diverse as asthma, chronic inflammatory diseases and liver problems.

“Given the possible chronic exposure to these microplastic particles through our diet, the results obtained suggest that their continued intake could alter the intestinal balance and, therefore, health,” says Victoria Moreno, a researcher at CSIC’s Institute of Research in Food Sciences (CIAL).

The researchers responsible for the study insist that knowing where these microplastic materials end up within the body and the consequences they may have in the short, medium and long term is vital. It is estimated that an average person could ingest between 0.1 and 5 grams of microplastics a week through their food and drink. In addition, the study showed for the first time that these microplastics can undergo transformations along the gastrointestinal tract and reach the colon in a structurally different form than when they were ingested.

Research in this field is still new and it is not known exactly in which tissues and organs these microplastics are accumulating. The assumption is that if the particles are large enough the body will expel them, but those that are smaller – the smallest are nanoplastics – may pass into the bloodstream and thus reach different organs. Although there are still no large-scale studies, traces of plastic have been found in samples of human placenta, as well as lungs, kidneys, liver and spleen. Experts agree that more research is needed on what effects these traces may have and also on how exactly they get into our digestive system. It seems clear that many microplastics are ingested through the consumption of fish and shellfish, as the oceans are heavily polluted by plastic products.

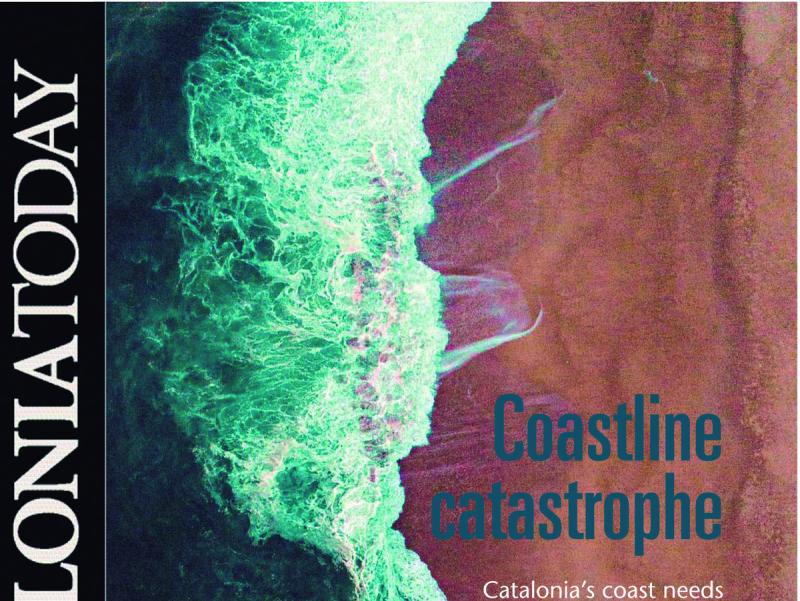

Despite efforts to recycle plastic, the amount of plastic that ends up in the ocean is huge. According to the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature), the total amount is at least 14 million tonnes a year, making plastic the main waste material to be found in the oceans. Plastic has even been found at a depth of 10,000 metres and trapped in Arctic ice.

There is talk of the planet’s oceans turning into “plastic soup”, and we know of five huge islands of plastic that have been created due to the convergence of sea currents and winds. Two of them are in the Atlantic (North and South), two more are in the Pacific (also North and South) and one is in the Indian Ocean.

With the Mediterranean Sea being a largely enclosed body of water with a lot of tourist activity on its shores, the presence of microplastics here is especially worrying. According to Greenpeace, between 21% and 54% of all plastic particles scattered in the planet’s seas and oceans are to be found in the Mediterranean.

It is estimated that the plastic floating or deposited on shores accounts for only 15% of all the plastic in the oceans. Much more plastic is in suspension. Over time, the action of water and the sun break the plastics down into ever smaller pieces that are then scattered throughout the marine ecosystems. It is when they reach a size of less than 5 millimetres that they are considered microplastics and this is when it becomes easy for them to enter the food chain, via fish, birds and marine mammals.

In 2020, scientists from the University of Hull in the UK published a review of 50 studies done over the previous six years on levels of microplastic contamination in fish and shellfish in different parts of the world. The researchers found that mollusks (such as clams, mussels, oysters and scallops) contained the highest levels. They also found that the most polluted animals were collected off the coast of Asia.

As for definitions, there is a distinction between microplastics generated from the fragmentation of larger pieces, those that from the wear and tear of fabric – microfibers – and those that are called primary, which get into the environment in the form in which they were originally synthesised. These are microspheres, spherical particles so small they pass through filters and purifiers. These tiny particles are used in exfoliating gels or detergents, for example. Greenpeace has launched a campaign to raise awareness of microspheres and countries such as the US and the UK have enacted restrictions.

feature health

How long do they take to degrade?

There are many types of plastic materials but all of them are derived from petroleum. Another thing that all plastics have in common is that they are extremely resilient and they take a very long time to degrade. To give some examples: a balloon takes more than 6 months; a typical plastic bag from the supermarket takes about 55 years; a disposable plastic cup can take up to 75 years; a cigarette lighter, some 100 years; plastic cutlery can take 400 years; a typical water bottle, up to 500 years. As for a fishing line, that can last as much as 600 years. What’s more, plastic degrades more slowly in water than on land. According to Greenpeace, more than a million birds and over 100,000 marine mammals die each year from plastic materials in the seas and oceans.