Land of Chopin

An American writer and socialite captures the beauty and grandeur of Mallorca’s Valldemossa

Travellers in Catalan Lands

So early next morning, in a light open carriage, we set out across the vega for Valldemosa. The dusty white road that ran between low walls over which clambered hedges of prickly pear and cactus; the houses, with their walls shaded by deep colonnades and marked in almost every case by one or two tall palm trees; the olive groves; the acacias and fig-trees and sycamores that bordered the road, combined to make a truly African landscape; while the acequias, or water-courses, hollowed in the tops of the walls to irrigate the thirsty fields, as well as the primitive water-wheels turned by blindfolded donkeys, made me think of the country round Tunis or Tangier.

Gradually the mountains drew nearer, and as we approached them looked gray and bald and dry. But when we came closer we could see little gardens hiding among the rocks, hedged in with myrtle, carpeted with moss and bright with wild flowers. Higher and higher we climbed through the foot-hills, steeper and steeper grew the deserted road, until, at an altitude of about fourteen hundred feet, we descried far above us a village with a church tower and a great pile of ancient buildings, long and irregular in form, set upon terraces and marked by venerable towers: the old Carthusian monastery of Valldemosa. […]

We had come to Valldemosa with the prospect of a double pleasure, for beside our enjoyment of the natural beauties of the place, we knew that a welcome awaited us from the family who occupied the oldest portion of the monastery, the part that had been the palace of King Sancho. Many well-known people—Ruben Dario, Sargent, Sorolla—had been their guests, and their library, in an old tower that Jovellanos had occupied during his exile, was filled with rare books and manuscripts, so we hoped that we should be plunged at once into the romantic atmosphere of the valley. This hope indeed came true, for no sooner had we arrived than an evening was planned in our honor. A score of young men from the village, with their mandolins and guitars, sang songs for us, especially an ancient type of bolero called El Parado […]

Among the guests were several who occupied cells in the monastery. When I say “cells,” you must not imagine the anchoretic abodes, four by seven feet in size, in which certain hermits used to pass their lowly lives. For, when Don Sancho’s palace was given over to the Carthusians, the monks began the construction of a great monastery (never quite completed) planned upon so vast a scale that a stately church, two cemeteries and several cloister courts were enclosed within it. Each “cell” consisted of three vaulted chambers of goodly dimensions, one of which was the monk’s kitchen and work-room, the second his place for meditation and prayer, and the third his bedroom. [...]

All three of his rooms opened upon his garden, placed on top of a long terrace and separated from those of his neighbors by high stone walls but commanding a vast view of the valley, so that when he stepped from his cell he looked into unlimited space upon a prospect that any poet might envy, filled with infinite variety and multitudinous detail: monticles topped with pilgrim-chapels, rocks of strange and varied forms, and terraces of almond, peach, and lemon trees that descended like giant steps to the narrow opening in the mountains through which Palma and the curve of its shore could be seen. [...]

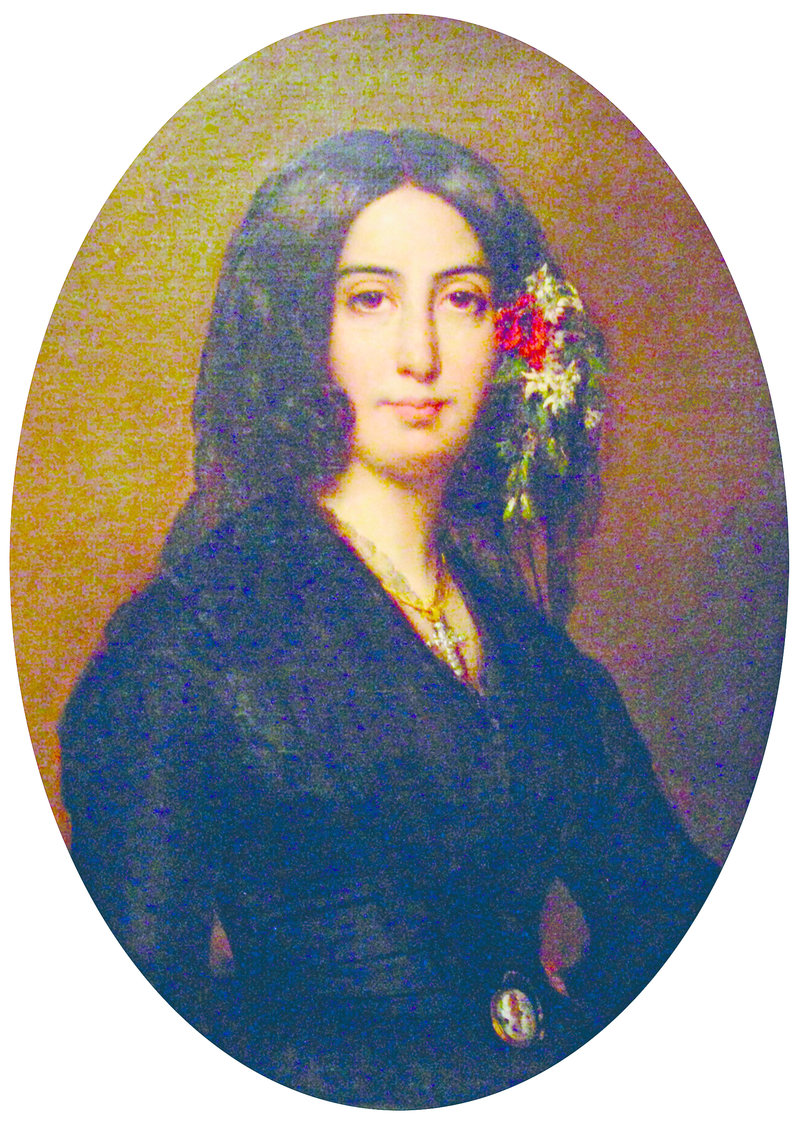

And so it is that these comfortable cells are now occupied as country houses by certain Mallorcan families who appreciate the charm of Valldemosa. To one of them attaches a particularly romantic history, for in it, strange to relate, Frederick Chopin spent a winter with George Sand, who, accompanied by her two children, made a voyage to Mallorca in 1838 in search of new sensations. As de Musset had accompanied her a few years before to Venice, so, on this occasion, the young, blond Polish pianist was her chosen companion. Soon after their arrival, Chopin fell ill with the first symptoms of the malady that was to carry him off in the full prime of his life.

Ernest C. Peixotto

Pere GifraOne of the five children of a family descending from Sephardic Jews, from early youth Ernest Clifford Peixotto (1869-1940) devoted his time and talent to art. The murals he painted for wealthy patrons and institutions throughout his career constitute today his most visible legacy, but he also excelled as an illustrator of articles and travel books. Born in San Francisco, where he took his first drawing lessons, in 1888 he moved to Paris to pursue further studies. The six years he spent there allowed him to meet some American impressionists and also to successfully display some of his paintings. When he returned to California, he was instrumental in founding a bohemian group, “Les Jeunes”, that briefly published a literary magazine. In 1897 Peixotto married the painter Mary Glascock, and began his lasting collaboration with Scribner’s Magazine. The couple published artistic texts and travelled across South America, Europe and the southwestern United States. As a result, he wrote the illustrated travel books Italian Seas (1906), Through the French Provinces (1909), Romantic California (1910) and Our Hispanic Southwest (1916). In 1921 he was awarded the Legion d’Honneur for his promotion of Franco-American relations. One of Peixotto’s post-war travel books was Through Spain and Portugal (1922), with relevant parts on Catalonia and Mallorca such as the description of the Charterhouse of Valldemossa presented here.