When everyone was suspicious

The Political-Social Brigade secret police became one of the main instruments of espionage and repression of the Franco regime, as well as a key player in helping the regime survive for some four decades

In his Dictionary on Francoism, Manuel Vázquez Montalbán wrote that the Political-Social Brigade, officially the Social Investigation Brigade and popularly known as “the Social” or “the Secret”, was “the true Praetorian Guard” of the Franco dictatorship. From the outset, the regime had considered its survival dependent on the extermination and systematic persecution of those it saw as political opponents; and it devoted itself heart and soul to this task. The repression lasted until the dictator’s final breath (and even continued after his death) and managed to keep a large part of the population acquiescent after the drama of the civil war and the series of summary executions in the early post-war period.

One of Franco’s interior ministers, Ramon Serrano Suñer, explains in his memoirs that the supporters of the Republic were considered “internal enemies” that were destined to be strongly repressed. Even before the end of the war, legislation appeared against those who had contributed to “creating or aggravating the subversion of all kinds to which Spain fell victim and who, from July 18, 1936, have opposed the National Movement with specific acts or with serious passivity.” This excerpt is from the Political Responsibilities Act, which passed on February 9, 1939 and which outlawed all “political and social groups” that had formed part of the Popular Front, “its allies, separatist organisations, and all those who have opposed the National Movement.”

Almost at the same time, the Political-Social Brigade, the main instrument of the Franco regime’s repression, began to take shape. The first time it was mentioned in the press was on April 18, 1939, in an article in La Vanguardia Española that referred to the arrest of Segimon Mas, a militant of the Marxist Unification Workers’ Party (POUM) and close friend of Andreu Nin, who had taken part in the fight against the attempted coup of July 18 in Cambrils. Two years after this first reference, the Social Investigation Brigade was created, which together with the Information Services of the Civil Guard and the Phalange, was in charge of political repression through surveillance, seizures of private correspondence, tapping telephone calls and arrests.

The Political-Social Brigade and the whole apparatus of political repression in general were made in the likeness of the German model. According to a 1949 British Foreign Office report, as revealed by historian Pablo Ancántara, the Brigades archives “are based on the Nazi model, ensuring systematic surveillance of all suspected enemies in the state.” All political cases fell within the Political-Social Brigade’s scope, which acted by order of the chief of police. The document also summarised the PSB’s methods, which remained unchanged until the dictator’s death: “The interrogation of a prisoner may include the use of cruel artefacts, which tend to force statements, later called confessions. At the end of the case, the prisoner is transferred to one of the state prisons and is subject to military jurisdiction.” Even before the end of the Civil War, in 1938, Heinrich Himmler, head of the Gestapo and commander-in-chief of the SS, proposed a cooperation agreement between the Spanish and German police, which was later signed in the 1940s.

Antoni Batista, author of a book on the Political-Social Brigade, La Brigada Social (Empúries, 1995), points out that this political police force was in charge of persecuting “everything that is not prosecutable in a democracy, all those rights whose prohibition a dictatorship defines as passive: thought, ideology, expression, gathering, demonstrating, striking.” The Brigade had spies embedded in anti-Franco organisations, universities, factories, and even churches. Some of their reports preserved in the archives of civilian governments give an idea of the regime’s obsession with keeping an eye on everything and detecting enemies everywhere it could.

Obsessive persecution

The Brigade was obsessive in its espionage. Batista’s research into police records found, for example, that the “Group II of Anti-Catalan Activities” had a file on such a dangerous figure as the Catalan poet Salvador Espriu. The document stressed that “he enjoys great prestige among pro-Catalan elements” and that “he has always shown himself to be a progressive Catalan nationalist, attacking the Regime. He enjoys special prestige for his book La pell de brau, in which insulting concepts against the Regime appear.” In reality, the insulting concepts were requests for dialogue between Catalonia and Spain. Another note referred to a lecture given by Josep Maria Castell on Espriu, stating that the offence they were both guilty of was that “they speak Catalan”.

Salvador Espriu is an example of the systematic persecution to which artists, workers, politicians and even clergy were subject. Espriu’s records were in the files of “Catalan-separatists” along with Josep Benet, Joan Manuel Serrat, Oriol Bohigas, Alexandre Cirici, Joan Brossa, Romà Gubern and Quico Pi de la Serra, among others. Another figure under suspicion was the singer-songwriter Lluís Llach. One of the many reports in his file pointed out that “the lyrics of his songs, all of which are in the vernacular language, are of a marked Catalan separatist character, hinting in his verses at the oppression to which Catalonia is subjected, and that the moment of its release is approaching.” Yet what worried them most was that “before and during the performance of his songs, he excites the audience, who often interrupt him with applause.”

Catalan music was systematically monitored, as it was seen as a platform for mobilising the masses, and what happened at concerts and the lyrics of songs caused the regime great distress. A good example is found in the report of the well-known concert that Raimon gave at the Palau d’Esports in Barcelona on October 30, 1975, only a month after the execution of Basque militant, Txiki. The somewhat paranoid-sounding police report said the event was attended by about 10,000 people “mostly young people between 20 and 22 years old, all of them hairy”. And that during the songs, people “applauded and shouted ’Freedom, freedom’ and ’Down with the regime’. The audience reacted like an enraged crowd.”

The clergy were also persecuted, including some well-known cases such as Lluís Hernández, who was mayor of Santa Coloma de Gramenet, Lluís Maria Xirinachs, a senator and a leading figure in favour of independence, and Joan Subirà, who combined teaching with journalism. Subirà’s file indicated that he had an “openly Marxist and separatist ideology hostile to the Regime”, with a “background related to elements of Workers’ Commissions”. And, above all, he was accused of making such dangerous requests as “send sweets to the detainees”.

Some failures

The Brigade also had some resounding failures, such as opposition actions they were unable to prevent or others where they arrived too late. One of these was what happened at the meeting in 1966 known as La Caputxinada, in which the authorities were too late to prevent the act of constitution of the Democratic Union of Students of the University of Barcelona. The regime sent the Brigade in force along with a squad of armed police, who made a lot of arrests. Yet to do so they were forced to violate the Concordat agreement with the Catholic Church and suffer the bad publicity that came with it. On top of that, a team from French television that had come to do a report on Raimon happened to be there and filmed a cavalry charge against a group of Capuchin priests sitting peacefully on the convent esplanade.

The Brigade also failed to stop the constituent session of the Assembly of Catalonia, the main platform of the anti-Franco opposition, which official reports described as a “constant concern” of the Chief of Police. On Sunday, November 7, 1971, politicians of all persuasions and representatives of social movements managed to gather together in the church of St. Augustine and draw up a manifesto for democracy and autonomy.

However, two years later, the Political-Social Brigade, in collaboration with groups of armed police, managed to arrest the Parliamentary Commission; some 113 people gathered in the church of Maria Mitjancera. In this case, a network of police informers had told the Brigade the day of the meeting. Based on the intelligence, they set up surveillance in religious centres, the usual meeting places for the Assembly. The Brigade closely followed the movements of the Assembly of Catalonia and managed to frustrate the first session thanks to reports from an informant, who provided them with the place and the password. From then on they listened in on the telephone calls of Dr. Joan Colomines,, who they considered to be the “organising soul” of the movement, as well as other figures like Josep Andreu Abelló, Antoni Gutiérrez Díaz, Marià d’Abadal and Joan Raventós, to whom they attributed the responsibility “of notifying people to attend the Assembly of Catalonia”.

feature A history of spying on Catalans

feature A history of spying on Catalans

“Self-proclaimed president”

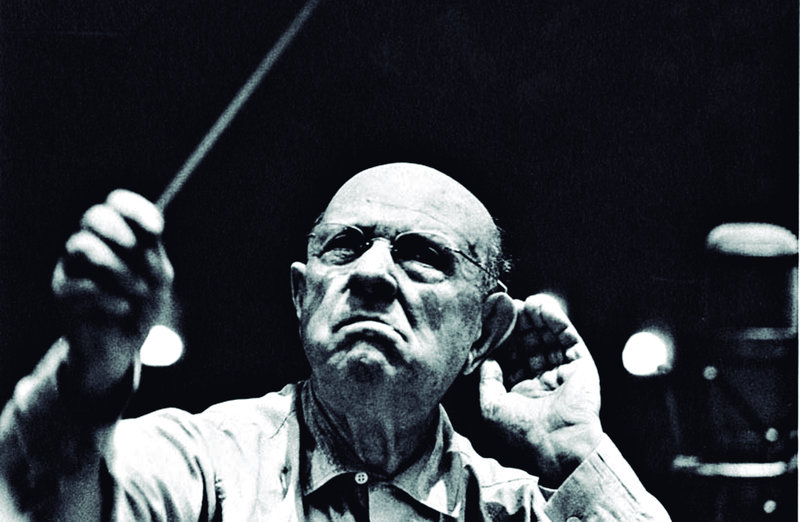

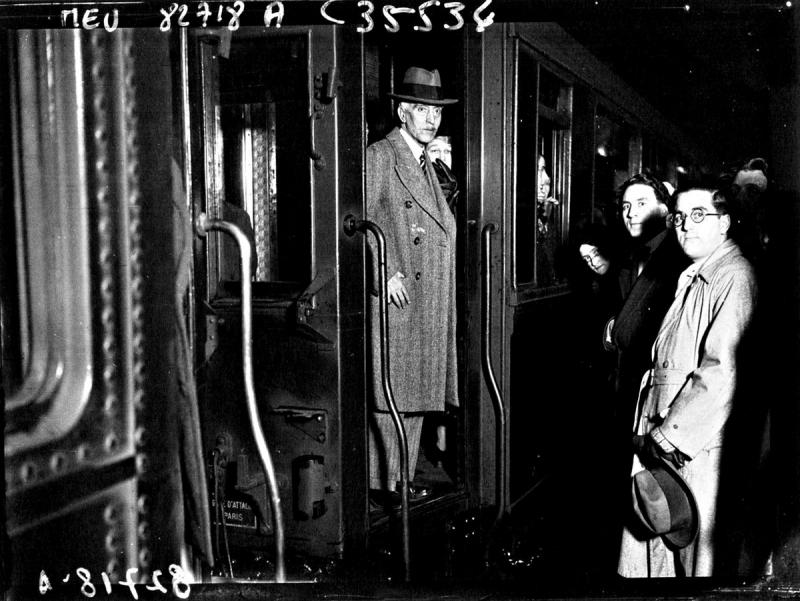

A dangerous cellist

The Franco regime also spied on musicians it considered to be “dangerous”. The historian Josep Maria Figueras, who has just published a comprehensive biography on the famous Catalan cellist Pau Casals, has located five voluminous files on the musician among the archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which are stored in the Archive of National History. All sorts of information is to be found in these files, such as memos, reports, notes, letters and press releases. And, as Figueres points out, they show the systematic surveillance that Casals was subjected to. The documents cover a very long period from 1935 to 1972, a year before the cellist’s death.

In some cases, the regime was not content to just monitor Casals, but also did its best to frustrate his actions. An example was on 23 September, 1965, when Antonio Garrigues sent a letter to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Fernando M. Castiella, boasting about getting a concert by Casals cancelled. “There will be no concert, so there will be no problem,” he wrote. On another occasion, the Spanish ambassador became furious after a charity concert by Casals went ahead in the Dominican Republic.