With the help of the Nazis

Catalan President Lluís Companys was persecuted and assassinated as a result of Spanish espionage, while Catalan politicians and writers played a role as spies in the Civil War and immediate postwar period

General Franco’s secret services shine in France.” This was the headline on the front page of the French newspaper Ce Soir on April 18, 1937. The Civil War had just begun, and the Spanish, with the collaboration of the Italian fascists and the German Nazis, had managed to build a considerable new espionage service, which did not go unnoticed by the press or the French authorities. The service had a very clear mission: to establish a network of collaborators and agents who would provide the Spanish Nationalists with information about the Republic. This service, together with the information obtained from the inside by the so-called fifth column, played an essential role in defining the military objectives of the fascist bombing and also in the outcome of the war. And it would, some time later, become the embryo of the future foreign information network of the Francoist government.

Spies at home

Franco’s espionage initially had a clearly Catalan tone, with significant names helping finance it, such as Francesc Cambó and Josep Bertran i Musiu, and others who acted directly as spies, such as Carles Sentís and Josep Pla. The main organisation was known as the Information Service of the Northern Border of Spain (SIFNE, in its Spanish initials), which was for the most part funded by Catalans. SIFNE operated mainly in the south of France and Catalonia, and was mostly dedicated to monitoring information, observing ships leaving for the republican zone and intercepting messages. On February, 28, 1938, SIFNE was absorbed by the Military Intelligence and Police Service. Paradoxically, the reason for this decision was not only the desire to avoid dispersal and improve efficiency, but also because “the hardcore at the Generalissimo’s headquarters considered it too Catalanist and monarchist,” as noted by historian Jordi Guix, author of a book on the subject.

Aside from SIFNE, there were more than five political and military information centres in the service of Franco’s Spain. Another organisation dedicated to espionage was the Spanish Refugee Aid Committee. Despite its name, it was engaged in carrying out documentation and information work for the Nationalist government. Catalan participation was also significant here as well. One of its leaders was Jorge Utrillo, a staunch supporter of Franco who had fled Barcelona a few days after the coup. The office was also a hotbed of corruption and dedicated to promoting repatriations in exchange for substantial commissions.

Although the freedom with which Franco’s spies acted caused a scandal in the French press, they continued to act with impunity, and were even helped by French agents. In a documented study on exile and Franco’s repression in France (Universitat de València, 2012), historian Jordi Guixé reproduced many notes and reports on military and civilian targets in republican Catalonia. Of these, 140 were written by José Camps, one of the most active spies. They contain information on a shipment of weapons to Valencia and Barcelona; plans for gas and explosives factories in Sant Andreu, which he describes as “one of the most important in the manufacture of explosives in Spain”; maps of the Sabadell airfield, where the planes were hidden and the main fuel depot in El Prat de Llobregat; and the exact location of 36 republican planes in Reus, including the ideal time to bomb them. There are even details about the exact location of President Lluís Companys’ anti-aircraft shelter in the Generalitat palace. Camps also made further reports, such as the one he sent detailing the casualties and damage caused by one of the bombings by Italian aircraft in the country’s capital.

Nazi complicity

Espionage, as one would imagine, did not bring an end to the war. With the victory of the Franco regime, the goal became to spy on, persecute and capture the main Republican leaders. Franco’s collusion with the French authorities was absolute, even prior to the German occupation. In February 1939, when the whole of Catalonia had been occupied but the war had not yet ended, what was known as the Bérard-Jornada pacts were signed, through which police commissions were set up to recover property in France and the conditions were established for the surveillance and repatriation of Republican refugees.

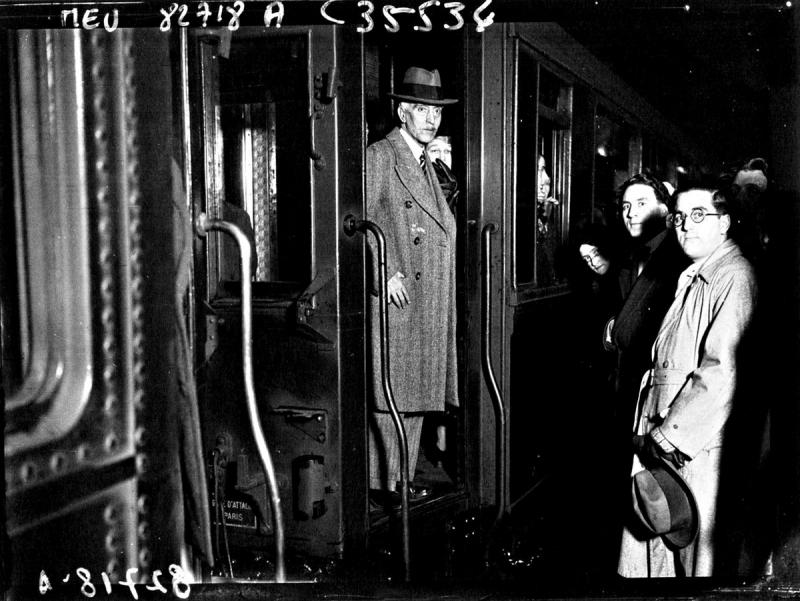

The situation changed completely on June 14, 1940, when the Germans took Paris. The armistice resulted in direct control of the north of the country through the Nazi administration and the establishment of a collaborationist regime in much of Occitania and northern Catalonia, known as the Vichy regime. From then on, the Spanish regime had free rein to pursue Republicans, some of whom tried to cross the Atlantic to take refuge in other countries, especially Mexico. A few days after the Germans entered the French capital, the Spanish ambassador, José Félix de Lequerica Erquicia, began to organise the police services with the collaboration of the head of the Falange in France, Federico Velilla, and agent Pedro Uurraca.

The arrival of the Germans in the French capital would be fateful for some Republican leaders, including Lluís Companys, Joan Peiró and a long list of others. To prevent the flight of Republican leaders, Spanish foreign minister Ramon Serrano Suñer sent the French ambassador a list with the names of more than 600 people to be arrested and extradited. On February 24, 1941, an agreement was signed between the Vichy government and Serrano Suñer, according to which the French government undertook “to hand over all Spanish refugees to the government of Madrid, according to a list to be drawn up by the Spanish bodies set up for this purpose, a list that will include all those people whom the Francoist authorities consider responsible for crimes committed in Spain, both common law and political crimes”.

In fact, many Republicans managed to cross the border or stay in France, as evidenced by a report from the French interior ministry dating back to the early 1950s, which puts the number of Spanish refugees still in French territory at more than 117,000.

The capture of Companys

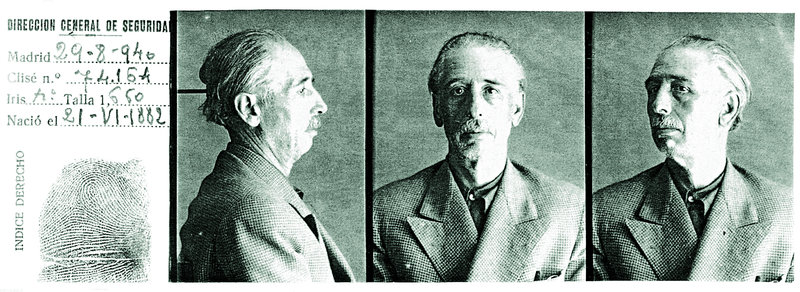

Many Catalan exiles were the victims of espionage and persecution, but the case of Lluís Companys is, without doubt, the most significant, due to the symbolism of his position, the procedure involved and the end he met with. Apparently, the services of the Francoist police attached to the embassy became aware of the Catalan president’s address after occupying the Catalan government’s modest Layetana office in Paris. In May 1940, even before France had fallen to the Nazis, Urraca told Madrid: “In a few days, ex-president Companys will be forced to leave Paris… and go to live in Le Baule, … where he will not allowed to move from.”

With the fall of Paris, events accelerated and the intelligence services of the Francoist police, controlled by Ramón Serrano Suñer, Franco’s brother-in-law, and the German secret police, the Gestapo, worked together in complete harmony. The same was true of the Vichy authorities, the satellite government of the Nazis in France. From that point on, all Republican politicians were subjected to strict surveillance and isolation and house arrest measures were also applied in order to keep some refugees away from the Spanish border.

On August 13, agent Pedro Urraca and five other men burst into the villa where Companys lived and, following a search and confiscation of everything of value, moved the Catalan president to La Baule police headquarters. Companys’ wife, Carme Ballester, described the arrest: “Two men dressed in civilian clothes and four in German soldiers’ uniforms [...] entered the house holding machine guns. And my husband and myself were then searched. After finding that we were not carrying anything, they set the whole house on fire and turned everything upside down [...] The soldiers kept pointing their guns at my husband, who was sitting in a chair, and I had to show the two men in civilian clothes where things were, but always with a revolver in my back.” The president was transferred to La Santé prison in Paris. Days later, two men in uniform and some soldiers showed up at his home and demanded the money that belonged to the Catalan government. The threat was a frightening one: “If you want, you can still save him, if you tell us where the other money and documents are.”

The day after this visit, on August 26, Pedro Urraca was commissioned to hand Companys over to the Spanish authorities. In his diary, the agent wrote: “He is no longer but a pool of life that wants to appear, before his accusers, as an honest man without blemish. It must be difficult for him in the environment that awaits him down there. This temporary freedom to travel seems to him like a gift that life gives him before abandoning him, and he wants to enjoy it with all his might. But the events of the moment are too strong for the world to deign to look at that man who is willing to make anonymous sacrifice and who voluntarily feels ready to forget his past.” As is well known, Lluís Companys was subjected to a very brief war council and assassinated at Montjuïc Castle on October 15.

feature A history of spying on Catalans

feature A history of spying on Catalans

Turncoats

Agent 447

Journalist Gemma Aguilera drew a portrait of Pedro Urraca, “the man who arrested President Companys”, in a work that won the October 2011 Essay Prize before being tuned into a book. In the prologue, then Catalan president Artur Mas highlighted the prevailing “climate of impunity”, a very current reference. Aguilera traced Urraca’s life before he participated in the arrest of Companys, making him an infamous figure in Catalan history.