The critical eye

A 19th century American animal rights campaigner observes the treatment of animals in Valencia

Women Travellers in Catalan Lands

The next day we left there for Valencia. The first part of the long journey we skirted the coast as we had done between Barcelona and Tarragona, and had our eyes gladdened by a constant view of the blue Mediterranean; but after a time the railway struck inland, and we were soon travelling through groves of orange trees well-nigh as thick as leaves in Vallombrosa. [... ]

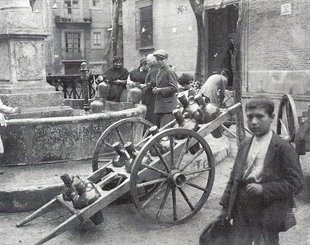

We found Valencia, where we stayed a couple of days, a city of considerable importance as a seaport, but otherwise possessing few attractions, although we were told that the people were unusually social and friendly. There, as in Barcelona, the custom prevailed of driving flocks of goats through the streets, and stopping them at certain places in order to give their milk to waiting customers. Each goat is provided with a bell hanging from a strap around its neck, as well as a muzzle to keep it from eating up all the tender plants along the line of its march, to say nothing of hand-bills and paper boxes. When it rains, these valuable animals are provided with an India-rubber, tightly-fitting blanket or cover to prevent their taking cold. They are milked out in the street anywhere apparently that any one comes up with a pitcher or bowl desiring a supply of the lacteal fluid. The tinkling of the bells around their necks forms an important feature in the city noises every morning and evening, and is likely to disturb the matutinal slumbers of those who hear it for the first time. In Valencia, in addition to the usual droves of goats, cows appeared upon the scene, some of the inhabitants evidently preferring their milk to that of their smaller relatives. Whereas every goat was furnished with a small bell, every cow had a huge one around her neck, giving forth the most unmusical sound possible, and attached to her side, by means of straps or ropes, walked her latest offspring, in the shape of a young bull. All these little bulls were muzzled, but at stated intervals the muzzles were removed, and they were allowed to refresh themselves at the maternal fount. Every cow was invariably accompanied by her son, a custom, the reason for which we could not divine until it was suggested to us that cows have sometimes a habit of refusing to let down their milk until they know that a portion of it at least is to contribute to the nourishing of their offspring. All these curious sights in the heart of a great city interested us extremely, while at the same time our hearts were saddened with the reflection that all these little bovines were being roared for the purpose of affording a holiday amusement, by their tortures, suffering, and death in the bull-ring, to a cruel, excited crowd of spectators. Ice appears to be almost an unknown substance in Spain, and, as the weather at this time of the year is very warm, there arises the necessity not only of obtaining milk fresh at one's door, but of having a market every day in the week. The market square on Sunday in Valencia was the most busy and animated spot in the whole city, and many of the stalls were not closed till three or four o'clock in the afternoon. Meantime the churches were well filled, for a more devout nation than the Spaniards can hardly be found on the face of the globe. In the great cathedrals several masses are going on at the same time until ten or eleven o'clock every day in the week, and in the smaller churches there is at least one mass every hour. We heard a beautiful musical service on Sunday morning in Valencia. [...] Two fine male voices in the choir sang a portion of a hymn, and the congregation responded by singing the remainder, with the organ for an accompaniment. When we left Valencia, as we could no longer follow the sea-coast, the railroad not yet being built, we decided to go to Cordova. It was a long, uninteresting and tiresome journey, lasting nearly twenty-four hours. [...] We shudder to think of what it must be in a second-class conveyance. Soon after leaving Valencia, our eyes were greeted with an unusual sight, that of a large number of rice fields. They were all covered with water to the depth of two or three inches, recalling to our minds what we had heard of the unhealthfulness of rice cultivation. The country after a time became evidently less fertile, as we could see from the nature of the crops, and during the greater part of the day our road led through the arid and rather desolate province of La Mancha, famous for being the theatre of the life and exploits of Cervantes' hero.

Caroline Earle White

The animal rights movement, one of the nineteenth-century reform crusades in which women participated most actively, worked on multiple fronts in the USA to reduce the suffering of horses, mules and other creatures. One of its staunchest supporters was Caroline Earle (1833-1916), who assumed a leading role in its development not only because she launched successful initiatives in animal defence but also because she challenged the control exerted by men within the movement, relegating women to subaltern positions. Raised in a Quaker family, her father was an abolitionist lawyer and her mother a social activist, cousin of women's rights advocate Lucretia Mott. They provided her with a fine education that included science, foreign languages and a deep social awareness. Her understanding of the cruelty against animals began soon. Throughout her youth she often demonstrated her sensitivity to the feelings of animals on the streets of her native Philadelphia, either protecting beaten horses or adopting abandoned pets. Inspired by Henry Bergh, founder of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty against Animals, in 1866 she began to garner support from upper-class Philadelphians. Not believing in the inferiority of animals, she became a vegetarian. In 1883, against the opposition of medical researchers and laboratories, she opposed vivisection and established the American Anti-Vivisection Society, which still exists today.