1066 and all that

On the 950th anniversary of the Battle of Hastings a new book examines the 11th-century Bayeux Tapestry, which tells the story of England's conquest

If you are in the UK, in your loose change you might just find a 50-pence coin issued this year with the queen's head on one side and what seems to be a medieval knight with an arrow in his eye on the reverse, along with the year 1066. This is clearly commemorating an event that happened in that year, but what country would commemorate the 950th anniversary –why not wait for the millennium?

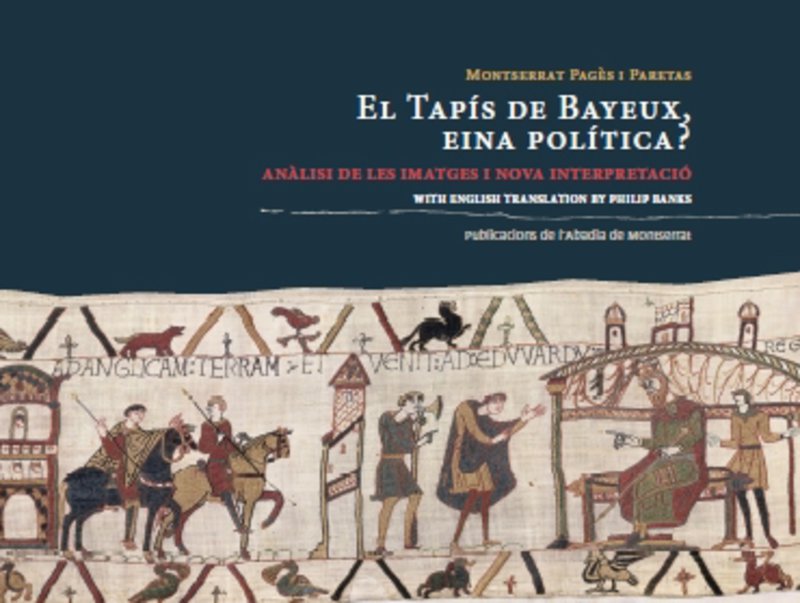

A new book in Catalan by Montserrat Pagès i Paretas, El Tapís de Bayeux, eina política? Anàlisi de les imatges i nova interpretació, with an English translation by the author of this article, will tell you more. However, in a nutshell, the event in question was the Battle of Hastings, which took place on October 14, 1066, near the town of that name on the south coast of England. So important was the event that 1066 is probably the only date in medieval history that most English people remember without an effort. This is partly because a humorous book from the 1930s with the title ‘1066 and all that'; it was famous because it contained two dates, one of which was 1066.

But what actually happened in 1066? In that year, Duke William of Normandy invaded England, believing he was the rightful heir to the throne after the death of the previous king –Edward the Confessor– instead of the Anglo-Saxon noble, Harold Godwinson. Not only did Duke William invade England, but he was successful. He managed to defeat Harold on the battlefield at Hastings, where Harold almost certainly met his death, becoming King of England and reigning until 1087.

This led to a change in dynasty and all the kings of England for the next 300 years or more had close ties with what is now France. There were also other changes: the arrival of a new French aristocracy in England, bringing with them a developed system of feudalism; they also built many castles throughout England and made wider use of a new architectural style, generally called Romanesque, but in England also known as Norman architecture. Perhaps the change that is most noticeable today was the introduction of Old French as the language of government and administration, which is the main reason why modern English is a fusion of diverse linguistic roots –on the one hand the pre-Conquest Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian influences, and on the other the weight of Old French (and Latin).

The image on the reverse of the 50p coin shows what is usually supposed to be the death of King Harold, killed by an arrow in his eye. It is derived from a very special work of art called the Bayeux Tapestry (actually an embroidery). Although now in the city of Bayeux in Normandy, it was made in Canterbury in England. The Tapestry vividly depicts, in a series of images, almost as if it were an 11th-century cartoon strip, 70 metres in length and about 50 centimetres high, the events of 1066, culminating in the Battle of Hastings itself.

The Tapestry is a key subject of academic study for historians and art-historians in the English-speaking world. Yet, it is also well-known outside academic circles. English people instantly recognise it, to the point that it has entered popular culture and can be found in the opening titles of many films (The Vikings, Bedknobs and Broomsticks, Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves) and TV series (Blackadder). Sadly, it is less well known in Catalonia.

This situation has now been remedied by the book written by Montserrat Pagès i Paretas, curator of Romanesque Art at the National Museum of Catalan Art (MNAC), and recently published by Publicacions de l'Abadia de Montserrat. Not only is it the first work to describe the events shown on the Tapestry in Catalan, but it also puts forward a hypothesis about why it was made and who commissioned it. The interest of this hypothesis meant that, when the author first showed me her text, I did not hesitate to encourage her to publish it in English to guarantee the maximum diffusion of her ideas. The end result is a bilingual work which, as someone who has studied the medieval history of both countries, I hope will make the period and this extraordinary, unique work of art much better known.

Catalan writer; English translator

Montserrat Pagès was born in Barcelona, although her family's roots can be traced to the Empordà. Having studied the Pre-Romanesque and Romanesque art of the Baix Llobregat in her undergraduate dissertation and doctoral thesis, since 1990 she has worked as a curator at the Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya (MNAC). The majority of her publications have been devoted to Catalan Romanesque painting. Her interest in the Bayeux Tapestry, this extraordinary, exceptional, yet enigmatic work of art, is a consequence of her profession as an art historian determined to understand the meaning behind images and to analyse them from all possible angles.

Philip Banks is a Londoner who came to Catalonia to do research for his doctoral thesis on early medieval Barcelona in the mid-1970s. He subsequently became an English teacher at the Escola d'Idiomes Moderns of the Universitat de Barcelona, although he maintains his interest in the medieval world.