The traveller A mildly deranged vision

A lesbian detective is hired by a glamorous woman, Frankie, who is in fact a transsexual to look for her husband, Ben, who turns out to be a woman. It is (you've guessed right) a comedy about sexual identity

My name is Cassandra Reilly and I don't live anywhere,” Barbara Wilson's narrator declares in the first line. The upfront statement sets the tone for Cassandra, Irish-American adventurer who works when she needs the cash as a detective or translator (if only a translator's life were so exciting).

This is no murder mystery. It is a crime story with barely a crime. There is an apparent kidnapping, but it is not really a kidnapping. Frankie offers Cassandra a lot of cash in London to search for her husband in Barcelona, but she has not told Cassandra the truth and nor does anyone else. Cassandra is happy to travel to Barcelona, where she can catch up with old friends and lovers, translate and work for Frankie. It sounds ideal, but soon becomes a nightmare. No-one, but no-one is who she seems to be. The not very believable plot soon lost me, just as it seems to have lost Cassandra, but the detective's swagger and the book's energy kept me reading.

Sex and satire

Published 25 years ago, Gaudí Afternoon is a novel of its time, though the title gives a humorous nod towards Dorothy Sayers' finest and most feminist novel Gaudy Night (1935). Barbara Wilson has written a comic adventure story with the underlying purposes of affirming lesbian identity and the diversity of sexuality. Cassandra is as promiscuous as any male stud, but she is sensitive to her women's feelings (if we take her word for it). Her life-style is the envy of many: travelling the world with a girl-friend in every port.

Serious as Wilson is about her sexual politics, she has a refreshingly satirical eye. Among her targets are New Age massages with April, whom Cassandra fancies; the uptight architect of children's houses, Ana, who fancies Cassandra; or Carmen, an Andalusian Catholic hairdresser (the book's most vivid character) who has a torrid relationship with Cassandra, but religious ‘principles' always prevent her going all the way.

Wilson also takes on the fad for magic realism. Throughout the book Cassandra is translating the massive, portentous and pretentious “The Big One and her Daughter” by Gloria de los Angeles, “the fifth author to be dubbed ‘the new female García Márquez'”. The chunks of magically real text are one of the best jokes in the book.

Evoking Barcelona

Wilson really knows Barcelona. She first came in 1970 and found parts of the old quarter still derelict: “everything reeked –in descending order, air to stone pavement— of wet black clothing on the line, olive oil, garlic, harsh tobacco, and piss.” Then she discovered Park Güell and the “magical and mildly deranged vision of Antoni Gaudí.”

Both the run-down old city and Gaudí's buildings are strong presences in the novel. Wilson records the joys of the seedy pre-Olympic city of the 1980s, recent, still in living memory, but lost. Her passion reminds me of Vázquez Montalbán proposing, not entirely as a joke, that the City Council open a Museum of Smells, to conserve the memory of a city being modernised and sanitised out of recognition.

Wilson gives us the Plaça Real, the sweat-filled bars, greasy streets, half-demolished tenements, or the no-star Hotel Palacio: “A dirty wooden staircase led up to a small lobby on the second floor, where a pair of pinched sisters glared at me.” At the market's “icy stands of fish…, the fishmongers looked as pale as their catch from long years of sunless filleting and wrapping.” She is a sharp descriptive writer.

The religious conservative Gaudí, though, is the surprise protagonist of this feminist novel. Numerous scenes refer to his buildings and Wilson has seriously good explanations of his architecture. Here is Cassandra reflecting on the Park Güell: “The crazy thing about Gaudí was that his structures were so absolutely sound, perfect parabolas capable of bearing enormous weight, and yet his surfaces were so irregular. They gave the appearance of being natural, of having been part of the planet for millennia, and at the same time looked completely new, completely unlike anything you'd seen before.”

Gaudí's sleights of hand fit well with the shifting sexual identities of her characters. Just as Cassandra is unsure who is who and sexual identities are fluid, so Gaudí's stone may flow into a tree-trunk and his curves place nature in city-centre buildings more effectively than any potted plant can. Much of the action takes place in a flat in the dirty, run-down La Pedrera, before it was spruced up by Caixa Catalunya 30 years ago.

Gaudí Afternoon is a very likeable book, full of bad and good jokes. A romantic comedy, with pace and no pomp, but some serious intent. It ends with one last joke on sex role reversal. A man and a woman think they might have a child together.

“Hamilton blushed. – It's a little unconventional, but I think it may work.”

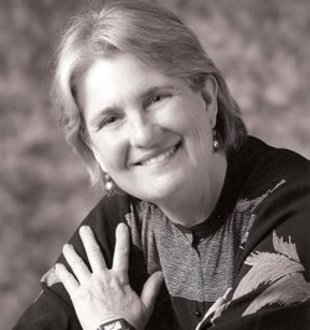

Born in Long Beach, California, in 1950, Barbara Wilson was brought up in a Christian Science family, described in her harrowing 1998 memoir Blue Windows. She discusses the complex conflict between religion and reality. Her mother died after refusing medical treatment for cancer.

Child of the 1960s, she travelled widely through Europe, escaping both her family and a United States at war. She explains in her powerful Incognito Street, How Travel made me a Writer (2006) that the challenge to understand new places stimulated her writing. Compulsive reader and writer, she was always recording where she was. Boldly she tried out different styles, imitating other writers before her own voice emerged.

She settled in Seattle in 1974, the year when she co-founded the feminist Seal Press. Like Cassandra Reilly, she worked as a literary translator, but from Norwegian, not Spanish. She founded the Women in Translation Press in 1989.

In the 1980s, she wrote three mysteries featuring a Seattle printer Pam Nilsen. Gaudí Afternoon, winner of a Lambda Award for Best Lesbian Mystery 1991, is the first of four Cassandra Reilly books, all set in different countries. In 2001 it was made into a Hollywood film.

In the early 2000s she spent several winters in northern Norway, investigating the Sami people. Around that time she began to be known as Barbara Sjoholm and today has a strong reputation as a writer of creative non-fiction, including The Pirate Queen about women who went to sea. She is author to date of some 25 published books, listed and summarised on her web-site www.barbarasjoholm.com.