A sad farewell

A British writer describes how she was forced to flee her beloved Mallorca at the outset of the Civil War

Women Travellers in Catalan Lands

I still had no desire to leave the Casa Blanca if I could find a companion, though I had made up my mind to sever my connections with the Island that summer, so I listened willingly to the prophets who said that the whole affair would blow over “in six weeks or so”. But, at the same time, I felt that it might be wiser to carry out my original intention, and pay a visit to the British consulate.

I found the building already barricaded with sandbags, and crowded with English and American visitors, all in search of assistance and advice. The harassed officials dealt with us patiently, and their opinion was that we should all be better off in our respective countries, though at the moment the problem was how to get us there. Apparently, though not yet officially sanctioned, a British destroyer might be told off to pick up refugees, and we were strongly advised, that as soon as this way of escape opened up, we should lose no time in taking advantage of it.

I returned with this news to Hortense, and after some debate it was decided that I should go back to the Casa Blanca—where I hoped that life would be peaceful, at all events for the next few weeks, and that she should join me there until we made other plans.

So, having settled things sensibly, as we thought, I left Palma by the evening train, passing streams of people carrying bundles of bedding, and cooking pots, preparatory to spending the night in the olive groves, in order to escape any possible aeroplanes which might take advantage of the brilliant moonlight to drop their bombs.

There were blue-robed, calm-faced nuns amongst them, shepherding the children of their orphanage, not to green pastures, but to hard and stony beds, with piles of pine branches for aromatic pillows. The youngsters evidently looked upon the whole thing as a most welcome picnic, as they chattered and laughed their way along.

I arrived home weary, but content in my decision to await the turn of events, and hoping that my optimism was going to be justified. […]

But a few days later, as I sat drinking chocolate on the veranda, and looking over the bay, with its shadowy hills and sapphire waters tinged with tourmaline, a dusty car drove up to the door. It was a messenger from the Consulate, to say that the political clouds instead of lightening were growing darker, and what might possibly be the last destroyer to leave the Island was due to depart that night. In answer to my protests he inquired whether I had heard of a shooting affray in which several Guardias Civiles had been killed, only a short distance along the coast from my house, and that if I did not wish to add to the burdens of the already overworked authorities, I would be sensible and go back with him. An hour was all he could give me in which to settle up everything, and pack two small suitcases to take with me. He brought a message from Hortense to say that she, too, had decided to leave for Marseilles.

Maria, with her complete inability to grasp any sudden or complicated situation, and to whom as yet the Civil War meant nothing, was helpless with misery, and could only wail, “Señora, if England has declared war on Spain, you must stay here. We will all protect you, and no harm will come to you. Only say that you will not go away and leave us”. […]

Yes, Majorca had been a very detached and tranquil place in those far-off days, a veritable Isla de la Calma and it was just that contrast which made the situation seem like a sinister nightmare. But after the first stunned moment everything was bustle and confusion. Arrangements had to be made for the household I was leaving behind, for an absence which might stretch into months or years.

Good-byes had to be cut very short, as we hurried through the little crowd of neighbours thronging the veranda, and into the waiting car, for our drive across the Island. We went straight into the sunset, and it was almost dark when we reached Palma, and the Civil Defence Office where I had to obtain an exit permit. Then on again through the suburbs of El Terreno until we reached the coast beyond, and the creek of Los Pinos, where we saw our destroyer, Grenville, lying out in the bay, while behind her the full moon rose out of the sea, and for a long moment held the ship framed and encircled, still as a picture.

Lady Sheppard

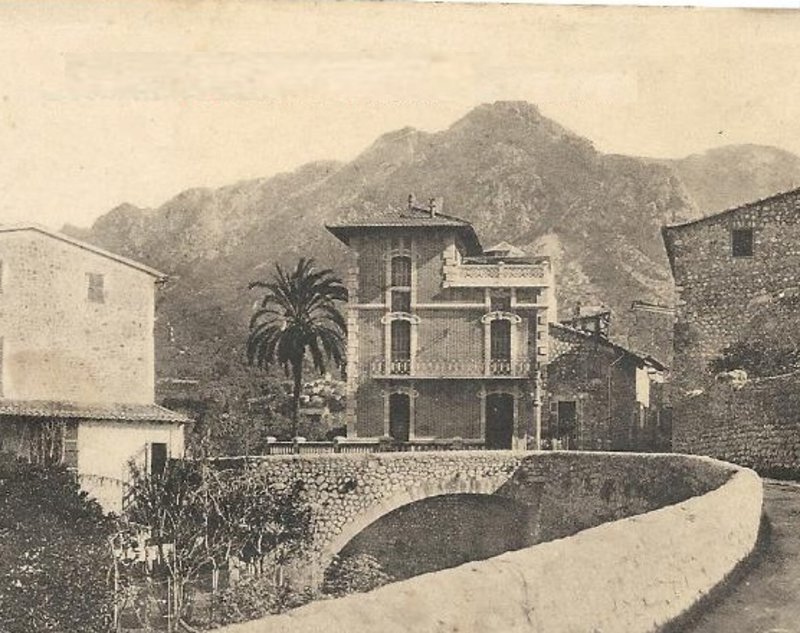

During the interwar years many Britons longed for a home in the sunny South, but not all of them could realize their dream. Among the lucky ones stands Margaret Kinloch Forbes Sheppard (c. 1880-1963), better known by her penname of Lady Sheppard. In the early 1920s this aristocratic widow toured all the Balearic archipelago in search of a house until she finally found it in Mallorca, in a village near Sóller that she nicknamed “Son Dichosa” (the happy place) but most probably corresponds to that of Fornalutx. Her book A Cottage in Majorca (1936) depicts life on the island in the 1930s long before mass tourism hit its ancestral customs. The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War forced her to abandon the island. During World War II Lady Sheppard remained in England, but as soon as the conflict was over she returned to her cottage. Mediterranean Island (1949), her third travel book, not only narrates this homecoming full of mixed feelings but also recalls incidents of earlier years. In 1946, it was difficult for her to think again of idyllic spaces in a world that had been so fiercely destroyed by a war fought on so many fronts. Moreover, Franco's Spain was no longer the spontaneous, innocent country she had known two decades ago, but a controlled state where silence reigned more than ever before. Yet, she was glad to meet old village friends. Lady Sheppard did not cease to travel and write. Her last book was Invitation to Sweden (1957).