Names and surnames of all those who died in the Spanish Civil War

Historian Jordi Oliva has published a book about the long journey to obtain the list of all the tens of thousands of victims of the conflict in Catalonia

How many people died in Catalonia due to the Spanish Civil War? And, who were they, what were their names, where were they from? Did they have a family, professional aspirations...? At the dawn of Spanish democracy, historian and cultural activist Josep Benet (Cervera, 1920-Sant Cugat del Vallès, 2008) struggled with these questions that had been buried during the long night of Francoism and that, despite the euphoria for political change, seemed to continue regardless: “A country cannot become normal if it does not know the name and surname of each and every one of the victims of a lived war. Studying this is an inescapable obligation that must necessarily be addressed.” Jordi Oliva was 21 in 1986, when Benet discovered him and involved him in the great project of counting the human cost of the Civil War in Catalonia. It was then that he began the mammoth task of counting the dead, including soldiers and civilians, men and women, children and adults.

Four decades later, in 2023, Benet’s disciple presented his doctoral thesis dealing with the complex puzzle that the Spanish Civil War left behind. In June 2024, the Democratic Memorial organisation published his thesis in a book, Cost humà de la Guerra Civil a Catalunya (Human Cost of the Civil War in Catalonia). “It’s not a finished project, nor will it probably ever be, but quantitatively and qualitatively we have come a long way,” says Oliva. However, the project has already gone much further than Oliva could have imagined when he joined the network of scholars (there would end up being about 200) that Benet created to obtain data town by town, city by city, county by county. Oliva was allocated Segarra county and in 1989 was entrusted by Benet with the coordination of the project throughout Catalonia.

During the 40 years of the Franco dictatorship, the human losses due to the civil conflict were completely ignored. “The Francoists had total ignorance of the number of deaths, even on their own side. It was of no interest,” says Oliva. Even after democracy was restored in the 1970s, it continued to be ignored. “Until recently, no Spanish government ever showed a desire to recover the memory of the people who lost their lives in the war. However, in the seventies, initiatives began to emerge in Catalonia.” The definitive boost came in 1984, when the Catalan government set up the Centre for Contemporary History, with Benet in charge. The study of the victim list began soon afterwards, to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the start of the conflict.

Living witnesses

In the early days, living witnesses were of great help. “We could still go to villages and interview people who had been there. It was an invaluable resource.” At the same time, there was a huge shortage of archived material. “In municipal offices, in the 1980s, I remember going into attics and finding documents covered with pigeon excrement.” Oliva has spent many months of his holidays researching archives throughout Spain. Getting access to the material has not been easy. “The problem is the lack of information that existed in 1938. For example, the archive of the Republican army’s statistics service, which managed the return of belongings of soldiers killed to relatives, has been lost.”

The difficulties in carrying out the study have been varied, with the lack of resources and, above all, a lack of will torpedoing it on multiple occasions. “The project has had to live in a permanent state of coming and going, between short-term interest followed by scandalous oblivion, according to fashion and media interest,” says Oliva. The most critical time was from 1995 to 2004 when the project was frozen. It was resurrected in the wake of the explosion of media interest in historical memory.

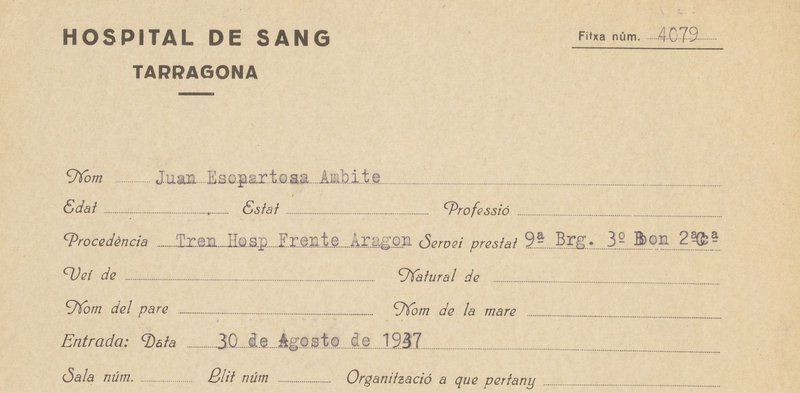

The new management of the Centre for Contemporary History entrusted Oliva with resuming the study with new goals: to computerise all the data collected, to incorporate foreign people who lost their lives in Catalan territory, and to expand the information on each death. “In the first lists, we only listed name and surname, age, place and date of death. From 2005, we added the date of birth, parents’ names, marital status, postal address, education, profession, circumstances of death, place of burial, and everything else known about the person,” notes Oliva.

The study has always been rigorous and that has often led to surprises. “Few people know that many fighters who died at the battle of the Ebre ended up buried far away, in Girona, Cervera, Manresa, Vallfogona de Riucorb... This is because the medical units were so overwhelmed that the wounded were evacuated, even though they were registered as dying in the Ebre,” Oliva reveals.

The study has not ended and “will always be subject to correction and improvement”. Nor is the total number of victims known: it currently stands at somewhere between 70,000 and 80,000. More work is still to be done, such as applying the more demanding parameters that were set 20 years ago to all counties, especially in the Girona region and Barcelona, where the obstacle has always been the capital city. “It’s very complicated to do research there,” the scholar notes.

Analysis of the data paints a revealing picture of the impact that the war had on Catalonia: 55% of the deaths took place in Catalan territory itself, with between 25% and 30% in Aragon. Obviously, male mortality in conflict situations outweighs all other deaths, and by age, the highest mortality peaks were among soldiers aged 18 to 20 (the Biberó levy from 1938 and 1939 was the most punished). The picture of the displaced Catalans fleeing the advance of Franco’s troops and the refugees from other parts of Spain who fled to Catalonia is very different. Here deaths of men and women are balanced at almost 50%, with the highest mortality among children under four years old, while 1938 was the deadliest year. During the retreat before Franco’s advance, the victims climbed to almost 15% of the total, twice as many as in the first six months of 1936. Meanwhile, the difference between the number of deaths on each side is huge: “for every dead Francoist soldier, there were nine Republicans”.

In 2019, the human cost project became dependent on Democratic Memorial with Oliva as its scientific advisor. In recent years, the historian, with Noemí Riudor and Martí Picas, has been unearthing unpublished documentation on the extent of the victims (already over 5,000) in exile in France during the immediate post-war period. “The human cost of the war did not end in February 1939 when Franco’s troops occupied all of Catalonia. The study goes further and there is still more to do. It should go as far as the last repression of the maquis in the post-world war period,” Oliva says, adding that it would be good to delve deeper into the concentration camps, the battalions of working soldiers and the militia in the first years of the dictatorship. Also still to be finished is the work of uploading all the data to the online database and making it open for consultation.

“Knowing what happened has begun to interest third generations more than the immediate generation of the deceased, who carried the family drama in silence. Grandchildren and great-grandchildren want to know. They are the ones who mourn the Civil War dead today,” says Oliva, who gives an example from the study: a young man from Madrid, whose grandmother died convinced her brother was murdered in Puente de Vallecas, but who was buried in Cervera. “The grandson has been to the cemetery to find closure.”

“The historian Benet said that the best way to move forward in memory is to do historical research,” says Oliva, who defends keeping the human cost project alive so the list can eventually be completed.

feature Historical memory