The passionate pianist

The Pole and Other Stories consists of a novella of 150 pages and five short stories. The ‘Pole’ of the title is Witold, a pianist from Poland, though also a possible ‘pole’ of attraction for Beatriz, organiser of his concert in Barcelona

Before The Pole, I had read nothing by J.M. Coetzee, which is neither a boast nor an apology: just that none of the random reasons one reads an author had led me to him. The Pole fell into my hands because it is set in Barcelona, Girona and Mallorca (as well as Warsaw); and my brief in these Catalonia Today articles is to review Catalan writers translated to English and English-language authors who set their stories in Catalonia. Of the latter, some writers really know Catalonia and want to pinpoint its complexities on the page; others use it just as an exotic setting. Coetzee’s book lies in the second category: there is no awareness of Catalan language nor descriptions of the cities where Witold and Beatriz meet. Indeed, despite the several Spanish people listed in the Acknowledgments, no-one seems to have told Coetzee that ‘polacos’ (Poles) is used in the rest of the Spanish state as an insult for ‘Catalans’.

No seduction

Witold the Pole is a 72-year-old with a mane of white hair invited to Barcelona to play Chopin. Beatriz is not too impressed by the rather cold style of play and, afterwards over dinner, the personality of Witold. After returning to Warsaw from Barcelona, Witold e-mails Beatriz that he wants to live the rest of his life with her. He invites her to accompany him on a two-week tour of Brazil. He e-mails constantly. Beatriz is a banker’s wife, occupied along with other upper-class women in organising monthly concerts in Barcelona’s Sala Mompou. Though her marriage, once passionate, consists now of separate bedrooms and lives, she has no intention of leaving her husband. She is unsure she even likes Witold, but is drawn into his passionless passion.

Witold is honest. There are no seductive manoeuvres. Rather, this unattractive man, like a shy adolescent, forces himself to say what he wants. He swears lifelong love in echo of Dante for his Beatrice. But where’s the ardour and feeling? Full of doubt but with time on her hands, Beatriz meets him when he comes to Girona to give piano classes and then invites him to Valldemossa, Mallorca, where she and her husband have a house (shades of Chopin and George Sand).

In most other contexts this would be a sordid story of an older, powerful musician harassing a younger woman. The Pole inverts this in part, for it is Beatriz who controls the rhythm of their relationship. Her ambivalence makes her a subtly portrayed character whereas Witold remains one-dimensional. Even as she finds Witold unattractive, his directness and desire pierce the uneventful surface of her life. However, it seems unlikely, to this reader, that she would respond to such a cold fish as Witold. Though Coetzee has created an interesting situation, he explains so little that Beatriz’s actions are unconvincing.

Clarity

As well as a story of improbable passion, Coetzee’s book is a meditation on art – on music and on writing. The five stories after The Pole feature an elderly woman writer (Elizabeth Costello, for those who have read other Coetzee novels). Elizabeth’s daughter tells her, in response to Elizabeth’s rejection of the idea that artistic beauty makes us better people: “What you have produced as a writer not only has a beauty of its own – […] shapeliness, clarity, economy – but has also changed the lives of others, made them better human beings. […] Not because what you write contains lessons but because it is a lesson.” Does playing Chopin well mean that Witold makes people better? Does great art improve people’s behaviour? The evidence of history says no; yet most people have experienced that thrill of good feeling on hearing great music...

The stories, basically conversations about writing between Elizabeth and her two children, ramble over ideas, though with just enough characterisation and place that they can be called stories. The most substantial is The Glass Abattoir, which posits whether people would stop eating meat if slaughterhouses with transparent walls were placed in the middle of cities so that everyone can watch animals being killed.

So, is the famous Coetzee worth reading? Clarity and economy are very much part of The Pole’s spare style. Slim though it is, the novella’s precise prose, stimulating ideas and subtle emotions make it an attractive book.

book review

Searching for Paradise

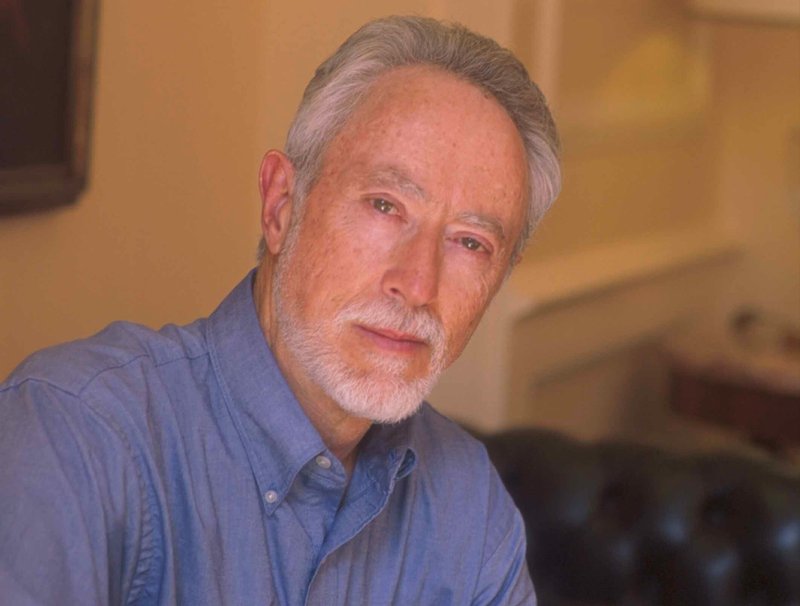

J.M. (John Maxwell) Coetzee, born in 1940, is the most garlanded writer in the English-speaking world. He has won the Booker Prize twice, for Life & Times of Michael K (1983) and Disgrace (1999). In 2003 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Though most of his books are set in his native South Africa, Coetzee has never been comfortable in his country of birth. He has moved all over the world, from South Africa to London in the 1960s, to the United States, where he was refused residency to continue teaching there, probably because of his active opposition to the US invasion of Vietnam, to Holland, and to Adelaide (“paradise on earth”) in 2002, where he worked as a Literature Professor. He became an Australian citizen in 2006.

In recent years, his interest in Argentine literature has led to his prioritising translations of his books into Spanish. With The Pole he went further. Though written in English, he had it published first in Spanish. He explained: “I do not like the way in which English is taking over the world… I don’t like the arrogance that this situation breeds in its native speakers. Therefore, I do what little I can to resist the hegemony of the English language.”

Publishing The Pole as El polaco in Buenos Aires is certainly a valid gesture against the dominance of English, but it has its irony too, as Spanish is also a major world language. To have published it in Catalan, given that Witold performs at the Sala Mompou and Beatriz is from Barcelona – now, that would have been a notable gesture against linguistic hegemony.

Apartheid

Coetzee shares with other white South African novelists like André Brink or Nadine Gordimer, the view that apartheid led to “deformed and stunted relations between human beings… South African literature is a literature in bondage” (speech on accepting the Jerusalem Prize in 1987). He has been both praised for his words against apartheid and criticised for not doing more. President Thabo Mbeki alleged that Disgrace showed racial stereotypes, but later congratulated him on the Nobel Prize.

In recent years, Coetzee’s novels have moved away from storytelling to intimate conversation, often between alter egos of the author: a tendency very clear in the The Pole and Other Stories reviewed here.