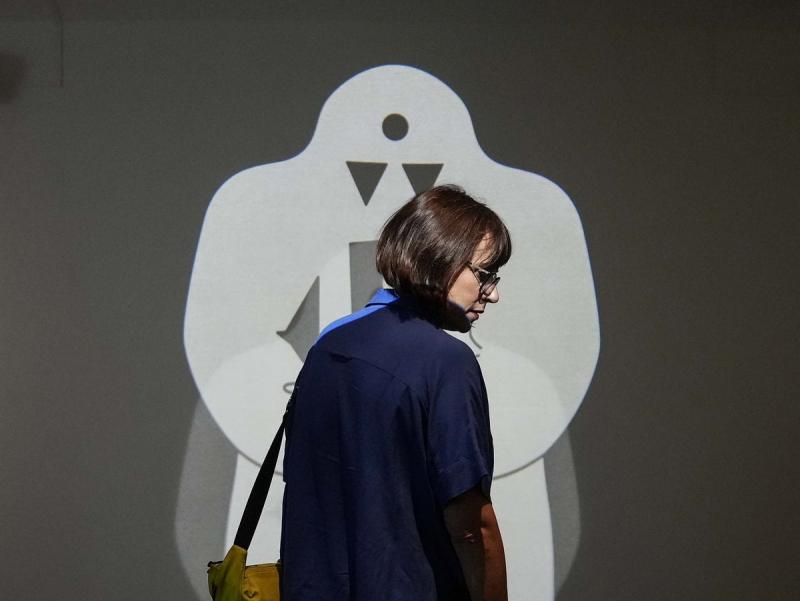

Picasso and Miró, face to face

On the 50th anniversary of Picasso’s death, the Barcelona museums dedicated to the two artists host an exceptional exhibition focusing on their artistic and human ties

It all started in the spring of 1922 with a pastry that Miró brought for Picasso. It is not clear who made the pastry, perhaps the Catalan artist’s mother or maybe the artist from Málaga’s mother, as both women knew each other. Picasso had already triumphed in Paris, the world capital of art, while 12 years his younger, Miró still had everything to do. It took the artistic genius a few days to open the door of his house on the Rue La Boétie (to the despair of Miró with his now stale pastry) but once he did the two men soon forged a friendship that would last a lifetime. The intense relationship between the two artists is well known but never until now has it been so thoroughly explored, through many anecdotes and shared experiences, both happy and sad, and with so much of the work they created in the same artistic atmosphere and in response to the same artistic stimulus displayed in the same spaces.

Miró-Picasso, which runs until February 25, is an exhibition that has been a long time coming, mainly due to the human and financial effort (about two million euros) it has required, but if there was ever a good time it is now, during this year’s commemoration of the 50th anniversary of Picasso’s death. Partly funded by the state, if you have the resources, why limit the exhibition to the Picasso Museum when you can also use the wonderful Miró Foundation? This makes it a dual exhibition but one with a single underlying thesis and a blend of works by both artists in each venue.

The hits

The exhibition boasts over 300 of the artists’ best work, drawn from some of the world’s largest galleries. Some have never before been displayed in Barcelona, or even Spain. Other works come from the respective collections of the two Barcelona museums, although the curators have been adventurous in their planning. At the Miró Foundation, for example, Picasso’s masterpieces Las Meninas (1957) and Harlequin (1917) are on display, the latter being the first Picasso to enter a public gallery when the artist gave it as a gift to the city of Barcelona. What’s more, it was one of the first works that Miró saw when he went to his friend’s parents’ house, on Carrer de la Mercè, and rummaged through the trunk that the artist had left containing artworks he had done in his youth in Barcelona. Meanwhile, the Picasso Museum has on display such Miró masterpieces as Flame in Space and Female Nude (1932) and The Morning Star (1940).

Picasso conceived Harlequin during his last major stay in Barcelona, between June and November 1917, on the occasion of the premiere at the Liceu of the ballet Parade by Serguei Diaguilev’s Ballets Russes, for which he made the sets, the costumes and the curtain. Miró attended the function but it is not known if they met in person. For their first confirmed meeting we have to go back to the anecdote of the pastry in 1922, when Miró made his first trip to Paris with the hope of putting on an exhibition and escaping the depression that had dogged him at home.

Picasso was key in dispelling his bad mood straight away. “After me, you will open a new door,” he told him, recalled Miró, who would become the main voice in this story of friendship because Picasso makes few references to it. Yet other evidence of Picasso’s affection for Miró exists, such as the three Miró paintings that had pride of place in his personal art collection. One was Self-portrait (1919) given to him as a gift by gallery owner Josep Dalmau, and which had been part of Miró’s first exhibition in Paris, and another was Portrait of a Spanish Dancer (1921), which he had bought from the art dealer Pierre Loeb. Both paintings, owned by the Picasso Museum in Paris, have made the trip to Barcelona. The third Miró work Picasso owned is a piece that the Catalan artist created expressly for his friend’s 90th birthday. The painting was lost for years before it turned up in a private collection outside Spain, and has now made a reappearance in the exhibition at the Miró Foundation.

Other pleasant surprises in the Miró-Picasso exhibition include The Three Dancers, lent by the Tate Gallery in London, which has never before been in either Catalonia or Spain. Picasso produced this groundbreaking canvas in 1925 following the death of his artist friend Ramon Pichot and while the painful memory of the suicide of another Catalan artist friend, Carles Casagemas, who had accompanied him on his first trip to Paris a quarter of a century earlier, was still fresh.

Similar but different

That macabre dance that emerged from Picasso’s brush fascinated the new generation of surrealist artists, including a Miró who took it as a reference but “never to copy”. This is the thesis of the team of curators (Margarida Cortadella, Elena Llorens, Teresa Montaner and Sònia Villegas, all four from the two Barcelona museums): “Picasso infused Miró with creative freedom and a transgressive impulse.”

Picasso also looked at Miró with admiration and respect. Friendship is stronger than ego and Picasso expresses his feelings in the dedications he wrote in his illustrated books (the only Picassos that Miró kept in his personal collection). “Your old friend”, he never tired of calling himself. So different in character (Picasso was volcanic; Miró was calm) the two men were close in political ideology and had a complete commitment to the Republican cause. Both also created a great artwork for the Spanish pavilion at the 1937 Paris Exposition, but with the difference that Picasso’s Guernica continues to convey its message about the horror of fascism while the message of Miró’s El Segador, also known as The Catalan Peasant in Rebellion, has remained silent since it was lost.

Such absences are compensated for by the works that fill the rooms with emotion in the Picasso and the Miró museums, both founded in Barcelona as the artists wished, rather than Paris or Madrid. In the Picasso Museum, Miró’s famous painting The Farm radiates light. Owned by Washington’s National Gallery of Art, it had not breathed the air of Barcelona for over 10 years. Yet the painting is still capable of raising goosebumps on the skin of even those who saw it last time it was in Catalan lands. Given the scale of putting on such an exhibition, it will be a long time until it, and many of the other artworks on display, will return home again.

Exhibitions art