Puncturing pretensions

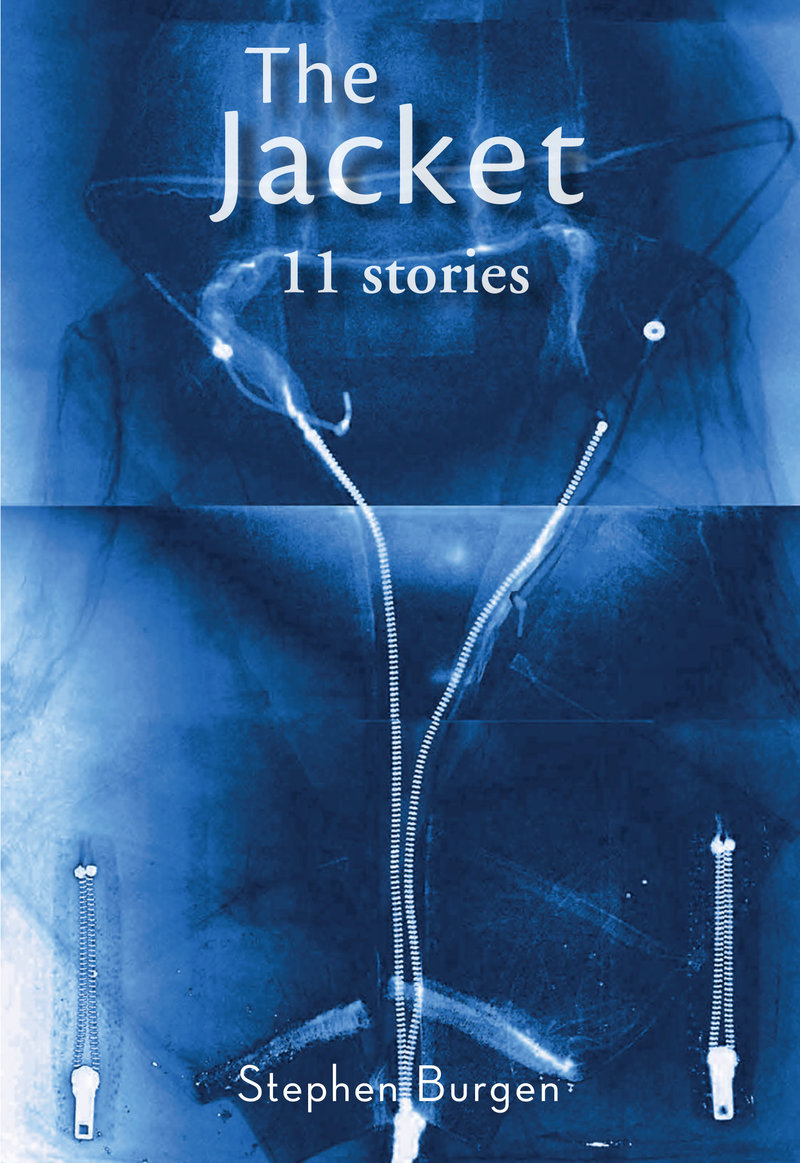

The Jacket is a collection of 11 short stories, varied investigations into relationships and domestic life, intense tales of longing, hurt and loss. None of them are just one story: Burgen is always weaving together two or several themes at once

The title story is a heartfelt study of bereavement, subtly told so that the reader feels something terrible is going to happen, before the realisation that the terrible, i.e. the bereavement, has already occurred. An unpleasant stranger at the door jolts Michael from the rawness and fragility of mourning into a possible future: “he had choices; he could choose life” (p.30). Several of Stephen’s stories contain such an unforeseen turn: he sets up situations that hook the reader and then defy expectations. It’s not an artificial twist, but a change that grows out of the situation.

Business ethics

Another story, The School, is a polemic on the fake values of Catholic-led business schools. “How to square heartless, profit-driven capitalism with Jesus and the moneychangers…?” (p.43), Stephen’s narrator asks rhetorically: i.e. how can you have Christian ethics if you’re teaching people to be pitiless capitalists? The answer is that the School just ignores all the many cases of unethical behaviour. It schools its students in ruthlessness: when a benefactor fails, he becomes a non-person, wiped off the web site.

The School also poses the more personal ethical problem of working at a place you don’t agree with. In several stories, a narrator/protagonist who is sceptical of power and pretension smartly punctures others’ hypocrisies. In The School, such a protagonist has to face his own dishonesty. Despite his scorn for religious deceit, to keep his job (this job he despises) he too acts unethically. In another story Epiphany the novelist narrator Gabriel also has to face his own dishonesty. He aspires to break from his pretensions and ‘live’ more authentically. “Reality for you is a sort of dry run for fiction,” his wife Daniela tells him (p.86). Unexpectedly longlisted for the Booker prize, his decision to “live in the moment” is blown away as quickly as a pile of ash. Wordly success buries honesty. Both these, indeed most of the stories, are comic – not laugh-out-loud funny, but bitterly ironic - as well as serious and poignant.

Like The School, Motherland has political content. Set in Barcelona in a possible near future, nationalist riots in a heatwave combine with the loving anxiety of a mother for her son. ‘Motherland’ is both ‘our country’ and a mother’s terrain. Stephen enjoys pinpointing contemporary mores. The callow tourists taking over the country sun-bathe half-naked and take selfies alongside the rioters. His paragraph on the tourists includes sharp observation of young holidaymakers, “their pale skin burnt pink”, of exploitation of immigrant labour and of a middle-aged woman’s surprise at the possessive/submissive behaviour of young men and women – all in 20 lines (p.69). These are dense stories. Read them a second time to pick up the detail: one of the pleasures of a good short story.

Precision

Half the stories, Motherland, Kiss, Ima, Ladies’ Man and Due Diligence are told through a woman’s eyes. Kiss deals with the folly of trying to recover past time. Middle-aged AnneMarie tries to relive her first kiss, but that teenage boyfriend’s turned into a seedy charmer. Ladies’ Man finds a bored mother craving adventure and getting more than she bargained for. In both these and several other stories, disaster seems imminent, but the protagonist survives and even learns from the experience.

The main exception to Stephen’s sardonic, often satirical tone is the painful 348 Grosvenor, the longest story in the book. It deals with mental breakdown and family collapse from a child’s point of view. This precise portrait of emotional cruelty in the home is tough to read, as Marcos, unable to grasp fully what is happening around him, withdraws into his own world.

Writing a good short story is notoriously difficult because you need to create a rounded world in few pages. Maximum precision is required. Stephen loves the power and precision of language. Here’s a random example: a young beggar was “wearing that mournful look, like a character in a Polish art house movie” (p.106); and another:

“She loved the smell of wet cement and plaster and sawdust; the stacks of slates and tiles awaiting their moment, sheets of plasterboard, rolls of scrim, the stream of sparks from an angle grinder, the ringing sound of a trowel splitting a brick.” (p.212)

These are fine stories, with polished prose, humour and sharp dialogue. Stephen’s touch is light, though his themes are often dark, i.e. he’s not just polishing a shiny surface. My favourite is Due Diligence, which features three women in a straightforward and moving story about oppression, art, dignity and death. The close second favourite, Victor, is both a rowdy satire on big business and a calm meditation on death, with a brilliantly rendered and unexpected ending. The twenty-page story includes problems with a teenage daughter, a nervous protagonist, a bullying boss, holding hands with a woman in a hijab. Stephen creates a full and rounded world, as in all 11 stories. The book is a pleasure to read.

book review

Novelist and journalist

Many readers may know Stephen Burgen’s name, for he is The Guardian’s correspondent in Barcelona. Over the last decade, he’s covered the independence process and written many an article, not only on politics but on culture and history.

Born in Montreal to British parents, he lived in Canada until he was 11 and the family returned to Britain. He first visited Barcelona in the 1970s and settled there in 2001 as the correspondent for The Times. Before that he had worked as a sub-editor on The Times international desk from 1992. Founding editor of Catalonia Today in 2005, when it was launched as a daily, Stephen also edited the ambitious but short-lived monthly, Inside Spain, in 2007-8. As well as The Guardian, he contributes to a number of radio, TV and press outlets, including the BBC, TRT Istanbul and the Financial Times.

Stephen is author of three other books. Your Mother’s Tongue: A Book of European Invective (1997) discusses insults and swearwords in some 20 countries. It was translated into several languages, including Spanish (La lengua de tu madre). A first volume of short stories, Afterlife, came out in 2014. The novel Walking the Lions (2002) is a sophisticated, witty thriller with political clout. It was written before the movement to honour and rebury the tens of thousands dumped by fascists in unmarked graves took off. The novel’s main character is an outsider investigating Civil War crimes who finds that a respectable Catalan nationalist with ‘a Falangist heart’ and criminal past is quite prepared to resort to murder today to keep murders yesterday hidden. The novel is both a gripping thriller with verve, style and pace and an investigation of a democracy impaired by reluctance to confront the ghosts of the past.

All his books, including The Jacket reviewed here, can best be obtained direct from the author at: www.stephenburgen.com