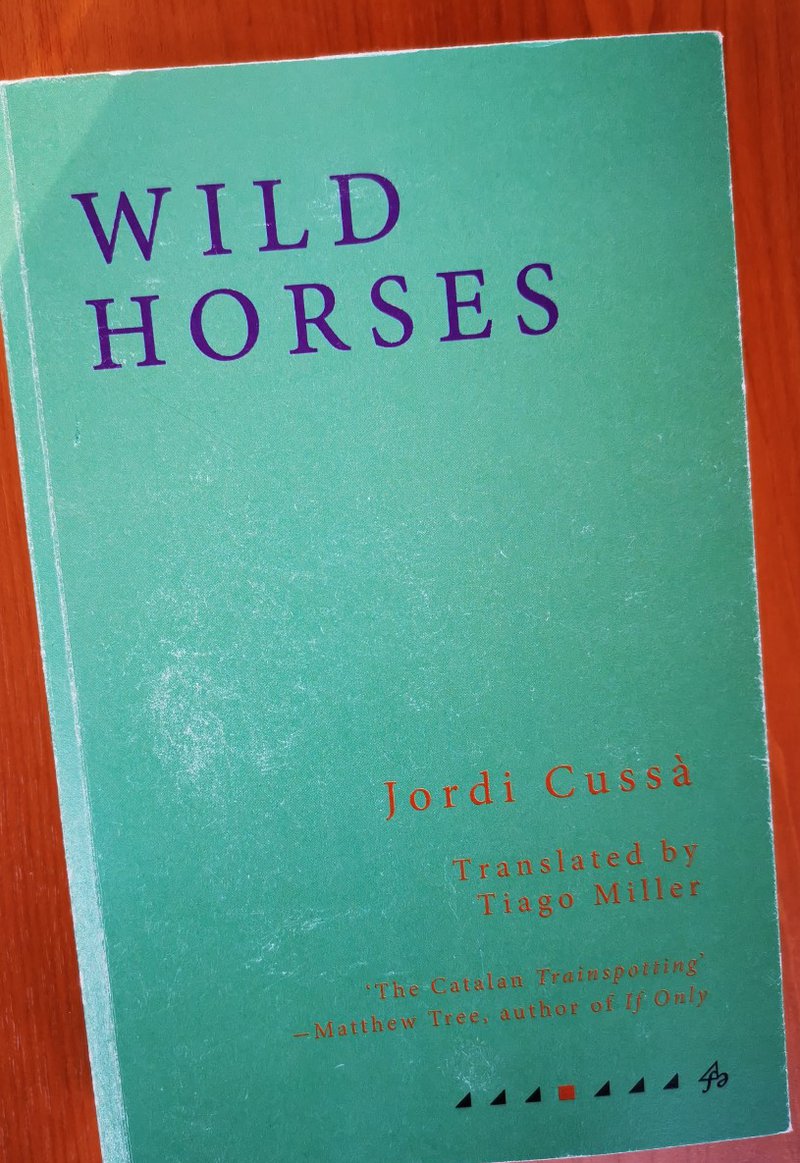

In deep shit

Wild Horses is a non-stop car-ride all round Catalonia, to Amsterdam and Naples too, but most surely through Berga, Tarragona, Torelló, Pont de Suert, Granollers, Blanes, Ripoll, Bagà, Puigcerdà, Solsona… you name the Catalan town and Àlex and Min have been there, selling, injecting, swallowing and sweating. Driving, living at full throttle.

You can take Wild Horses as a morality tale on the early deaths and ruined lives of hard-drug users - something that Cussà poses in the opening pages when at Lluïsa’s funeral her brother Peptic Pep, crazed by grief and deliberately fuelling his grief, assaults her user friends in the cemetery- OR as a paean to living in the present with as many chemical and sexual highs you can get and fuck the future. Fermí (or Min) puts it like this: “I like smack. I like the v-i-b-e… I don’t want to change my life. I want to savour it to the full” (p.339). Min knows he’s in deep shit, but with bravado he tells his friend and the book’s main narrator, Alex: “[Shit’s] fine once you recognize the smell and get used to the taste” (p.339).

Lifestyle Groove

Throughout the novel there is a to and fro about heroin users as being “hooked not just on the drugs but also on the lifestyle that came with them” (p.63). Alex, addict and survivor, ticks off the attractions of the lifestyle: social insolence, indifference to the future and “above all, the groove, as artists and execs call it, of being busy all day long, up, down, left, right, in, out, like someone with a non-transferable, transcendental task” (p.63). It stops you thinking too much.

Wild Horses moves between the 1980s and 1990s, but is mainly set in what was the Catalan (and Spanish) drug epidemic of the 1980s. Vázquez Montalbán called the mood a few years after the fall of the dictatorship desencís (disenchantment) because the new democracy, controlled by the right-wing, Catholic, corrupt Pujol, was profoundly disappointing. For part of the generation younger than Vázquez Montalbán’s, drugs became a way to cope with fewer jobs (despite greater social freedom) and the hopes for a better future squashed by the same old exploitation. Adding up to desencís.

One of the revelations of this novel to an outsider like me is that it is largely set in rural Catalonia. As Matthew Tree writes in his Introduction: “…people were busily shooting up in some of the country’s most picturesque towns and villages” (p.8). Heroin was not just an urban phenomenon, but was scattered among forests and farmhouses. Alex and his friends are always on the move, dealing to pay for their habit, driving daily over hills and plains to sell to a user in a village here, a town there. This is no still, reflective novel. The movement of its characters, the speed of their lives, roars off the page like their battered cars accelerating in a screech of burnt rubber to the next deal and fix.

The Deadbeat Generation

The novel is narrated in sections of varying length, often of only two or five pages, by several friends. It moves forward and back in time as much as it drives all over the country’s geography. Time is not linear, but fractured. The subject matter could well be monotonous, but it’s not, because the writing is magnificent. Cussà’s dialogue is vivid and inventive, often obscenely affectionate, sometimes fabricating new words. The first-person narrators roll along in colloquial riffs reminiscent of Jack Kerouac: Cussà is aware of this, several times having his characters call themselves the “Deadbeat Generation”. At times there is a delightful mix of colloquial rhythm and academic verbosity. Sometimes, it should be said, verbosity drifts into longwinded wandering (e.g. p.96: “these and many more similar questions referring to the different levels…etc.”). Perhaps this is part of representing the drug-filled minds of these university-educated users; or just that Cussà is attempting to philosophise on freedom and slavery, on illusion and reality. The story, the anecdotes speak for themselves. The novel is honest and humorous about sex and other bodily functions (diarrhoea, sweats, highs, aches, shivers). Throughout, rock music, the soundtrack to the rapid cars and the speed of time, is quoted and played.

This colloquial, fast-moving, druggy novel is a major challenge to a translator. Tiago Miller manages brilliantly to transfer Cussà’s style and tone across the language ravine. He finds equivalents to the novel’s invented words and even invents his own wordplay, as in this brief example: “The mo(u)rning procession” (p.15), or in a sentence like this: “When you’re starving without a cookie crumb, the Toot Fairy never comes a-calling” (p.93). A bold translation, it transmits the energy and rhythm of Cussà’s powerful novel.

One last, important point: the wildness of the characters’ lives, the road-novel aspect, the slangy dialogue, all in all the book’s glorious precision and pace, do not mean that it was thoughtlessly scribbled. The novel’s quality shows that Cussà put enormous effort into careful construction and composition. Chapeau!

book review

Happy writing

Jordi Cussà died in July 2021 in Berga, the town where he had been born 60 years earlier. He began writing stories in the 1980s, the decade when he became a hard-drug user. Wild Horses, published in 2000, was his first novel and is his best-known book. It was followed by some 15 other novels, two collections of stories and poetry books.

He was also a translator from English to Catalan (Capote, Patricia Highsmith, Yeats and Shakespeare, among others) and author of six performed plays, some put on at Berga’s Anònim Theatre, which he co-founded in 1978. At his death, the prolific Cussà was completing a further book of stories and a volume of poetry, and was writing the text for a graphic novel of Cavalls salvatges (Wild Horses).

Though suffering for many years from lung disease, he was prolific. A few days before he died, Cussà learned that his penultimate novel El primer emperador i la reina Lluna had won the Crítica Serra d’Or prize.