Tourism - Just a passing fad

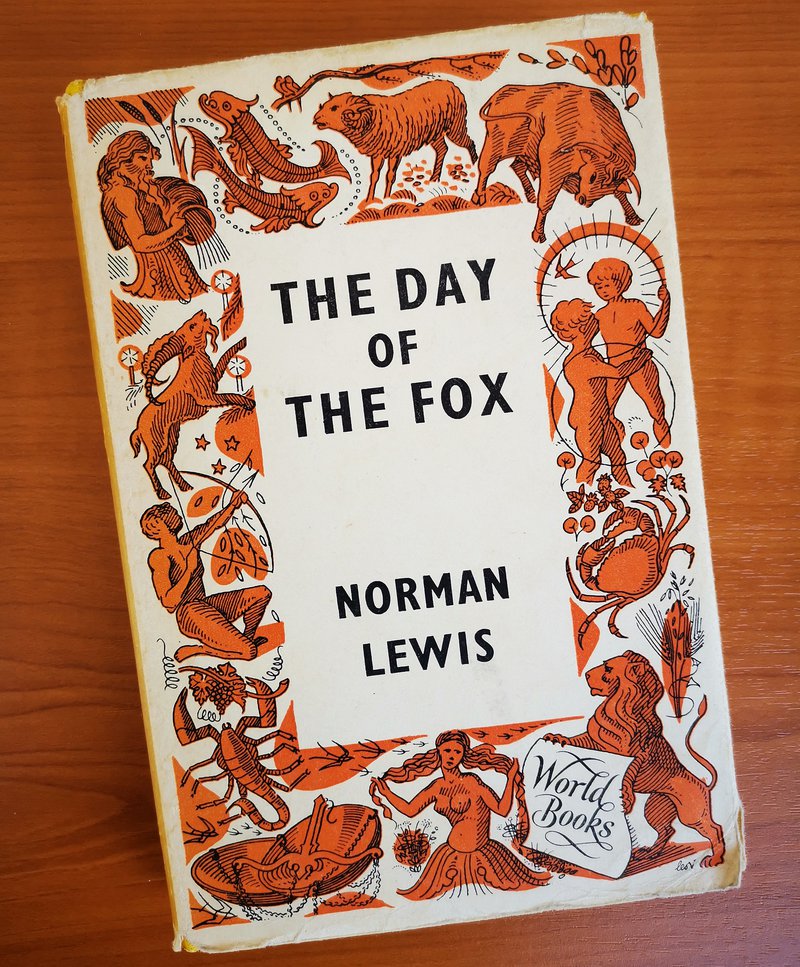

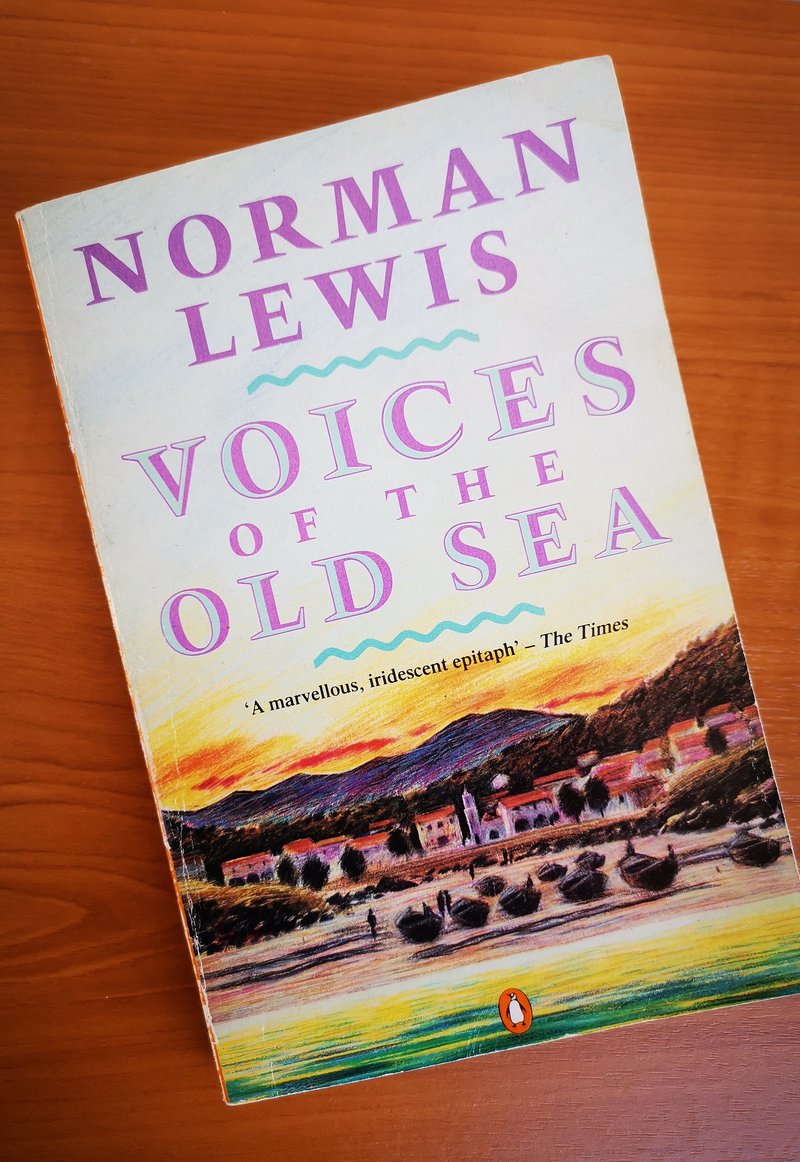

At the end of the 1940s Norman Lewis spent three springs and summers in a Costa Brava fishing village he calls Farol. Voices of the Old Sea tells a classic story of how an impoverished village, little changed for centuries, is suddenly convulsed by the arrival of foreign tourists.

The first and longest section of the book describes Farol as it was; the second and third, its rapid transformation. In this first section Lewis explains the villagers’ lives and beliefs. His dialogue is precise; and his tone, both ironic and sympathetic. No-one likes the church (though they don’t mind Don Ignacio the priest as long as he doesn’t talk about God), they hate the neighbouring village, they avoid the dictatorship’s police.

Pagan

They are mystical about the sea, not allowing animal skin (no leather shoes) on their boats, and follow the indications of the travelling ’Curandero’, who has remedies for everything, whether obesity, pregnancy, legal questions or illness, and who knows when and where the tuna shoal will arrive. The Curandero, much more influential than the doctor or priest, is too pagan for Franco’s regime, which means he has to live clandestinely. Finally, the police discover him and beat him up. Though village life may seem peaceful and eternal, Lewis does not let readers forget the recent Civil War.

Farol’s economy depends on two big shoals of fish, tuna in the autumn and sardines in the spring. When these fail, the village lives on credit and goes hungry. Lewis admires the solidarity of the fishermen, who discreetly leave part of their meagre catches in the boat for starving widows. He is respectful to the village’s numerous eccentrics, such as Carmela (’boss-eyed with straggling grey hair’) who secretes left-overs among her clothes or Don Alberto ’the reactionary aristocrat… who lives on air’. Lewis lodges with the large, authoritarian ’Grandmother… with the face of a Borgia pope… who was inclined to make God’s mind up for him’. He becomes friends with Sebastián, a ’bold and romantic-looking’ fisherman whose character is meek. As marriage was always put off for years while men saved for a house, the village prostitute Sa Cordovesa is an accepted figure.

Farol was ’the least accessible coastal village in north-east Spain’, which made me think of Cadaqués, but Farol is not Cadaqués because it is overrun by feral cats and Sort, a village full of dogs and cork oaks, lies just 5 kilometres inland. If any reader does know where Norman Lewis stayed, please tell me…

Pleasure-boats

During his second summer, Lewis witnessed the arrival of Muga, a cheerful black-marketeer who reminded him of ’a Japanese samurai on the lookout for someone to pick a fight with’. Muga is cunning, patiently winning the fishermen’s acceptance of his plans. He aims to turn the village into a holiday resort. He has roads paved and street lighting installed. He buys up houses. He persuades the bar to clean itself up. He advises the shop to stock Andalusian souvenirs, because that’s Muga’s idea of what the French want. And he was right! Even today, Lloret or Platja d’Aro’s souvenir shops are full of castanets, bull-fight posters and wide-brimmed hats that have extremely little to do with Catalan tradition.

The locals grumbled about the tourists (a passing fad, they hope at first), but soon found out how much holidaymakers paid for a pleasure-boat trip. By the end of Lewis’ third summer, only one fisherman was still fishing for a living.

Norman Lewis tells a painful story. He is romantically affectionate towards people whose way of life was destroyed in just a few years. Without nostalgia but with sadness, he portrays this moment of change, when tourism for profit crushed impoverished tradition.

book review

Norman Lewis

Norman Lewis (1908-2003) wrote 15 novels and 20 non-fiction books, mostly travel or memoir. He is most famous for Naples ’44, his account of the city after the fall of Mussolini.

Lewis was particularly attracted to traditional cultures that were just starting to change under the impact of the modern world. This is the case with the books on Catalonia reviewed here and others that he wrote on Nicaragua, India, Sicily, Burma and Indonesia. The moment he was proudest of was his 1968 Sunday Times article, with photos by Don McCullin, ’Genocide in Brazil’, which inspired the founding of Survival International, an organisation that protects the rights of indigenous tribes worldwide.

Observer

His was a colourful life, with three marriages, the first to a Sicilian, giving him inside access to the Mafia (about which he wrote The Honoured Society, 1964). Before writing he had been a photographer, an umbrella salesman, a motorbike racer and a soldier during World War 2. He liked to tell how he was capable of spending time in crowded rooms and afterwards no-one would remember he was there. He wanted to be unobtrusive, an observer. It is surprising that in such closed societies as ’Farol’ the suspicious fishermen accepted him even though he did not speak Catalan. For sure, he had a talent for being unobtrusive, but there is also I suspect considerable poetic licence in the conversations he describes.

Lewis had the gift of immersion in the present. Not religious, not thinking that humanity can improve, he sought happiness in the immediate, ’the intense joy I derive from being alive’.

Though he did much to inspire the boom in modern British travel writing that combines personal experience with information about out-of-the-way places, he is not so fashionable or popular now as when he was writing. This may be because of a certain floweriness in his descriptions: lush, rich prose that is a little over-rich, like too much sugar in a cake.