Ukraine: genesis of the new globalisation

Just over a year since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the conflict is still very much alive and has caused a sudden change in the process of globalisation that first began with the end of the Cold War in December 1991

The war in Ukraine has left globalisation in the dustbin of history. The perpetual happiness that the West associated with the globalisation that began with the end of the Cold War in 1991 is now over. That era that we thought had no productive limits and nothing to contest the hegemony of the USA no longer exists.

Economic and political liberalisation was the magic recipe for globalisation until February 2022. The opening of new markets even reached former communist countries, such as China, which embraced a capitalist model so as not to be left behind. In this time, the US has managed globalisation with unilateral arrogance and with contempt for the loser of the Cold War.

The first cracks appeared in 2007, when at the Munich Security Conference Vladimir Putin called for Russia to get a piece of the globalisation pie. It was not out of any dream of restoring Soviet greatness, Putin wants nothing to do with that, and in fact he accuses Lenin and the Bolsheviks of boosting Ukrainian nationalism, which led to the creation of an independent Ukraine and the erosion of the historical ties between Russians and Ukrainians that existed under the tsars.

The US reaction to Putin’s request was to tighten the noose and further expand NATO’s borders as far as Russia itself. This violated verbal agreements between Mikhail Gorbachev – the last Soviet president – and James Baker – US Secretary of State – not to expand NATO’s borders beyond the reunified Germany. It was a show of unnecessary disdain for a country with wounded pride and with the world’s largest nuclear arsenal. In 1994, Kyiv handed over the nuclear weapons it inherited from the Soviet era to Moscow in exchange for guarantees that Ukraine’s borders would be respected. But everyone went on to do whatever they liked and since February 2022 we have seen the consequences.

More than one side is responsible for this war, although obviously the degree of responsibility is not equal. The new globalisation that began in February 2022 places us in a scenario of permanent global competitiveness and tension. This affects, firstly, the economy, and secondly, global geopolitical stability. As we see in Ukraine, the US will do everything it takes to maintain its global unipolar hegemony in the political, economic, social, cultural and military spheres that it gained in 1991.

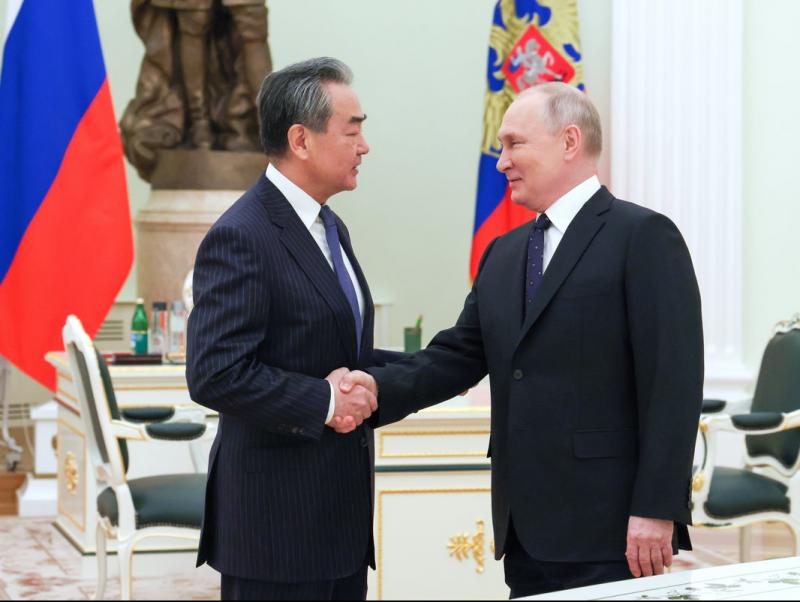

For its part, Russia has shed the backseat role it was given during globalisation. Russian oil, gas and other resources, added to the strengthening of its military – although not its quality, as we are seeing in this war – and the adoption of a profound nationalism to help it overcome the bewildering loss of identity that came with the disappearance of the Soviet Union are the foundations of Putin’s Russia. At the same time, Russia has consolidated its influence over neighbouring eastern states that were former members of the Soviet Union, sometimes through diplomacy and sometimes through force. It also has Belarus on its side and has secured China as a major trading and political partner, without neglecting its influence in North Africa and places like Syria. How things develop remains to be seen, but for now it has managed to bury globalisation.

China aspires to be the real counterweight to US power in the new global order, but this is an ambition that is beyond the Russian Federation. It will emerge from this war with its ability to establish alliances with other states reduced by US efforts to isolate it, while it has shown that technologically it is not up to the required level. Russia’s forces have not been able to carry out the quick and effective offensive that was expected, while huge military aid from the US and its European partners has allowed Ukraine to resist. In short, the war in Ukraine has begun a new phase of globalisation characterised by the competitiveness and permanent aggression between the US and its favoured partners towards those who aspire to challenge its world hegemony head-on, such as the Russian Federation and China.

We have not gone back to the Cold War (1945-1991) because there is no face-off between two opposing ideologies, communism versus capitalism, as almost no one questions the neoliberal capitalist model as the main driver of today’s world. But we are immersed in a climate of cold war. We have regained mutual distrust on a global scale. Since February 2022, the culture of confrontation has been steadily returning.

Another reality we have to get used to under the new globalisation is the contraction of markets, with vetoes on the purchase and sale of products depending on their origin. Initially this means permanent inflation, although exempt will of course be the large energy and armaments industries. For them, the situation is win-win.

Most clearly affected by all this is the relationship between Russia and Ukraine. The historical, cultural and territorial ties between the two have been broken. Russian military aggression has shaped a Ukraine that only looks towards Central and Western Europe. Western Ukraine, the part historically most deeply anti-Russian and pro-Western, has won the game, with most Ukrainians deciding to cut ties with Russia.

Ukraine’s future

Ukraine will most likely emerge from this war with its eastern territory amputated. Putin cannot afford not to do this, as the war must bring him some benefit. The regions most likely to end up in Russian hands will be Donetsk and Lugansk, while the annexed Crimea will stay part of the Russian Federation. Zelensky will also be faced with the considerable task of rebuilding the country. And let’s not forget that Ukraine has been living for months on financial injections from the US and the EU, which sooner or later will end. It would not be surprising to see a kind of Blinken plan – in honour of the current US Secretary of State – that emulates the Marshall plan that after the Second World War injected millions of dollars into Western Europe, and at the same time guaranteed European markets for Uncle Sam’s agricultural and industrial products.

The other big problem for Ukraine is and will continue to be the volatility of its eastern borders. If the new globalisation means permanent tension on a global scale, it will be the same for Ukraine and Russia on a local scale. Ukraine’s best bet to relieve this pressure is to enter NATO and let the alliance – in other words the US – manage its military defences. It is the most viable formula given the support so far provided by the US and NATO but this formula was also one of the triggers for the war. It seems unlikely that Putin would accept such an arrangement unless he had no choice.

Who has the most to lose? Without a doubt it is Ukraine. And the tragedy is even greater if we think about the demographic problems facing the country. An entire generation will be psychologically threatened by the possibility of a new war to add to the dead on the battlefield and the civilian deaths, the war crimes that may have been committed, and the emigration of key sectors, including personnel trained in the academic, scientific, business and administrative fields. All of this makes rebuilding the country more difficult.

The future of Russia

As for the Russian Federation, it is also losing a significant part of its population, from a generation mostly born after the Soviet era. It is a generation for whom the hardships of the 1990s and the sacrifices are distant. As is the Great Patriotic War against Nazi Germany that has been used to justify the war in Ukraine. At the same time, there are the Russian dead and wounded, the numbers of which are higher than might have been expected. In fact, the Russian military has been the big loser of this war, showing a lack of efficiency and requiring the help of paramilitary organisations. Yet this is unlikely to bring Putin down, as he stabilised the country economically, politically and socially after the chaotic Yeltsin period. For many Russians, Putin is a guarantee of stability, which is precious in the Russian mentality. We may never know whether the post-Cold War globalisation was better than the new globalisation, but one thing is clear, it is here to stay, and Ukraine is the one caught in the middle.

feature International

feature International