Submerged memory

The waters of the sea and rivers guard a rich cultural heritage in the form of wrecks and remains that allow us to see into the lives of our forebears, as can be seen in a new exhibition at Catalonia’s Museum of Archaeology

An animal hair brush, a leather bag, a cork and a wooden pulley. These objects from hundreds of years ago, which are on display in the exhibition Naufragis. Història submergida (Shipwrecks. Submerged history) at Barcelona’s Museum of Archeology (MAC), all have one thing in common: they have been preserved thanks to the sea.

Underwater archaeology is a young discipline but in 40 years it has brought to light a wealth of historical knowledge that had lain hidden beneath the waters of the sea and rivers. “The treasure is not the object itself, but the historical information it gives us,” says Rut Geli, director of the Centre for Underwater Archeology of Catalonia (CASC), which is based in Girona which this year is celebrating its 30th anniversary.

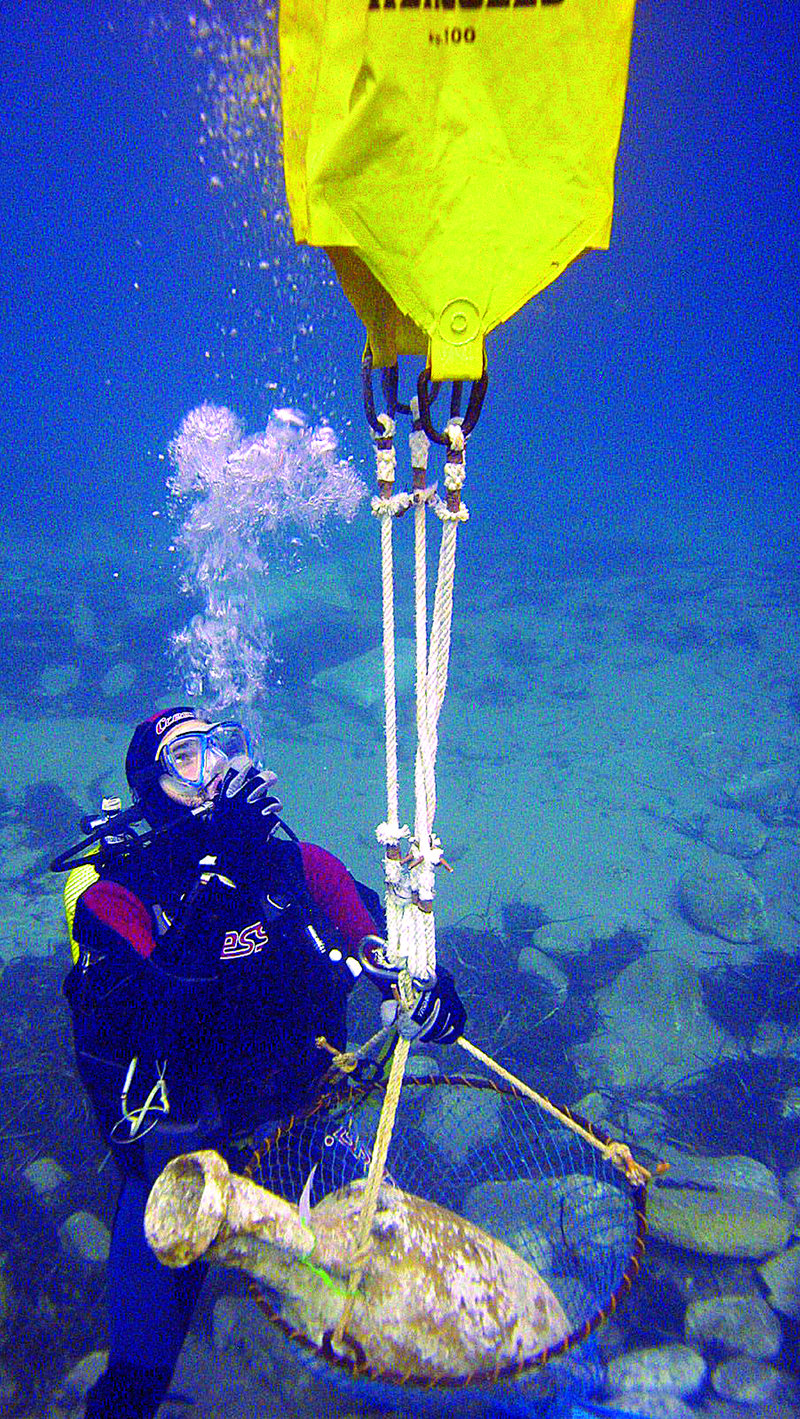

With the MAC exhibition as a major showcase to publicise the work that has been done and is being done, the CASC is preparing a new season of excavations. In June they will be in Empúries, and in July and August they will be in the northeast of the Formigues Islands, in Palafrugell. Here they will be excavating the country’s best-preserved Roman wreck, which lies at a depth of 46m, the deepest that Catalan nautical archaeologists have ever worked.

The sunken ship, Illes Formigues II, is an exceptional case, as the wreck’s wooden structure has been preserved as well as its cargo, which includes some 200 amphorae. Yet this 20-metre-long ship from Baetica (now Andalusia), which was carrying salt and fish sauces when it sank, has not escaped looters. Much of its cargo has already been vandalised or ransacked, especially in the fifties, sixties and seventies, when the regulations were lax.

It was the uncontrolled pillaging of underwater remains with the onset of mass tourism on the Costa Brava that sounded the alarm. The embryo of the CASC goes back to 1981, when the Girona provincial council created the first post of underwater archaeologist in Spain. Xavier Nieto got the past and went on to become the centre’s first director.

“Everything had to be done from scratch; from training specialists to raising awareness of the need to protect underwater heritage,” says Geli, who points to the importance of two key developments: the setting up of Catalonia’s Underwater Archaeological Charter, and the drawing up of a catalogue of underwater heritage sites.

This inventory is still a work in progress. It currently contains documentation on 855 points of interest, but the list expands year by year. In recent years, the impact of climate change has disrupted the ecology of the Catalan coast, revealing unprecedented remains. Storms such as Glòria or Filomena, for example, exposed two 19th century wrecks that are now being studied on the coasts of Salou and Sant Pere Pescador.

Most of the known sites are concentrated on the northern Costa Brava, for the simple reason that it is a part of the coastline with relatively little sedimentation and so shipwrecks are usually easier to find. In terms of historical period, most are from the classical and modern eras with fewer from the Middle Ages. Two exceptions, however, are Les Sorres X, a mediaeval ship now on display the Maritime Museum in Barcelona, and the Barceloneta I, which can be visited at the History Museum of Barcelona.

Yet these two ships are also exceptions in the sense that wrecks are generally only removed from where they are found if they are at risk of deteriorating due to human action (looting, for example) or due to natural threats (erosion, for example), or if it is in the interest of science or education, says Geli.

In recent years, Unesco has shown a strong commitment to safeguarding underwater cultural remains in situ, and last year the organisation issued seals of good practice to two CASC projects. One was the Cap de Vol and Cala Cativa I wrecks in Port de la Selva, which are similarly constructed vessels from the Roman period used to transport wine from Catalonia to Narbonne. The other was the Deltebre I, an English ship that ran aground at the mouth of the River Ebre in 1813, during the Napoleonic Wars.

The alarming regression of the Ebre delta keeps archaeologists on their toes. The discovery of the Deltebre I was made by a fisherman from Amposta in 2008 and what followed was a decade of study. It was a unique opportunity to see back in time because of the ship’s cargo: munitions for the attack on the besieged city of Tarragona. The Deltebre I was part of a fleet of one hundred and fifty vessels, eighteen of which were stranded as they retreated to Alicante. Five, including this one, were never recovered.

Despite the large amount of material recovered, which includes sailors’ belongings, such as a slingshot, a lice comb, and a syringe, again some of the remains have been looted. Finding an intact wreck is extremely rare, and there has only been one case in Catalonia: the Culip IV, a small vessel that crashed into the cliffs of the cove of the same name in the Cap de Creus headland between 78 and 82 AD. Covered in Neptune grass, the wreck went unnoticed by scuba divers and looters until a CASC team discovered it in the mid-1980s and studied it in detail.

The Culip IV may have gone undisturbed by human predators but not from the other great enemy of the shipwrecks, Teredo navalis, or naval shipworm, which made a feast of the ship because it overturned when it sank and lay with its keel exposed. Only a few fragments of the ship’s structure have survived but this is offset by the recovery of its rich cargo, including products from all over the Mediterranean: 79 amphorae of Baetic oil, over 4,000 ceramic vases, both plain and decorated that were also from present-day Andalusia, and 42 lamps made in Rome.

feature heritage