A deep Picasso

The artist’s museum in Barcelona shows off the results of a scientific investigation in collaboration with other institutions that has uncovered ‘picassos’ hidden in four recycled canvases from his blue period

There is little fear that we will never run out of Picasso. And it is also better not to assume that we already know everything there is to know about the painter’s work from what we see on the surface. As an artist, Picasso is extremely deep, in a radical and at the same time somewhat disconcerting sense. Experts already knew that, especially during times of financial hardship, Picasso reused some canvases that he had already painted on to create other images over the top of them. However, new technology has now allowed us access to these Picasso works that were completely invisible to the naked eye. Light has been shed on these underground picassos, bringing them to life with exciting sharpness.

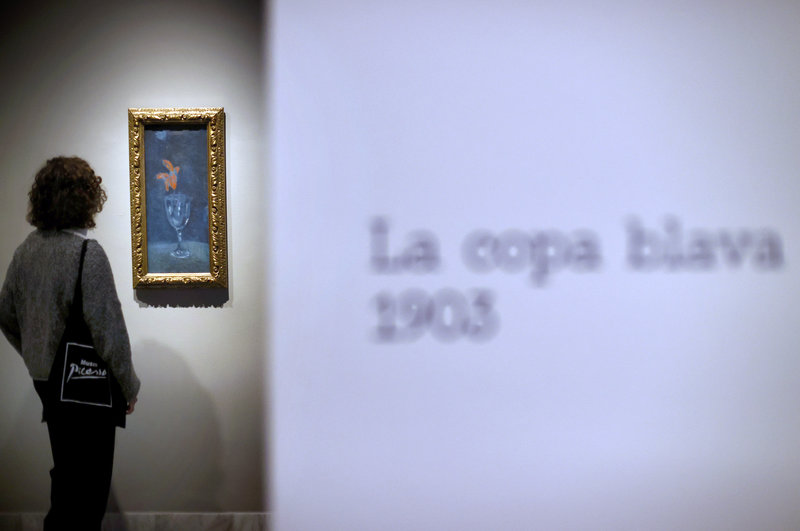

The museum dedicated to the artist in Barcelona has led a pioneering investigation along with a number of other major institutions into four of the most iconic works in his collection. The results are as astonishing as those obtained by any archaeologist excavating the earth for rich remnants of the past, and they are now on display until September 4 in the exhibition Picasso. Projecte Blau (Picasso. Blue Project).

The set of artworks examined with different combined techniques (radiography, infrared, X-ray, high resolution photography, microscopy, and so on) belongs to the artist’s blue period, which occupied him between Barcelona and Paris from 1901 to 1904. These are the years in which a sad Picasso was in mourning over the loss of one of his best friends, Carles Casagemas, who shot himself in the head in a restaurant in Paris. The dominance of the colour blue in many of the works from this time reflect the artist’s melancholic mood.

The standout work from this period is the painting La Vie, which today is owned by the Cleveland Museum of Art in the United States. A few years ago, it was discovered that another artwork that had been thought lost was hiding below the painting: Last Moments. This was a painting that Picasso had presented in his first solo exhibition at the Quatre Gats and then at the Universal Exhibition in Paris.

The Picasso Museum’s Blue Project also includes the artist’s 1903 painting, Roofs of Barcelona. Beneath this work that the artist composed in his workshop on Riera de Sant Joan in Barcelona just before he settled permanently in Paris there is a layer of paint that he rejected: a naked couple that show many similarities to La Vie.

There are also two figures buried below his work from 1901, Still Life. Appropriate to the melancholy style of Picasso at this time, the figures are not looking at each other or communicating in any way. The artist eventually painted over them, but he kept some of the motifs of his original idea, such as the table at which they sat.

“Picasso would not have done the still life we celebrate today if he had started from a blank canvas,” says Reyes Jiménez, head of the preventive conservation and restoration department at the artist’s museum on Montcada. Yet she adds that she does not believe that the only explanation for the reuse of these canvases is the financial hardships of the young Picasso. In her opinion, the artist also wanted to challenge the viewer with visual games. “He could have completely painted over the pre-existing images, but instead he decided to adapt and morph them. He intentionally leaves traces of the early paintings,” Jiménez explains.

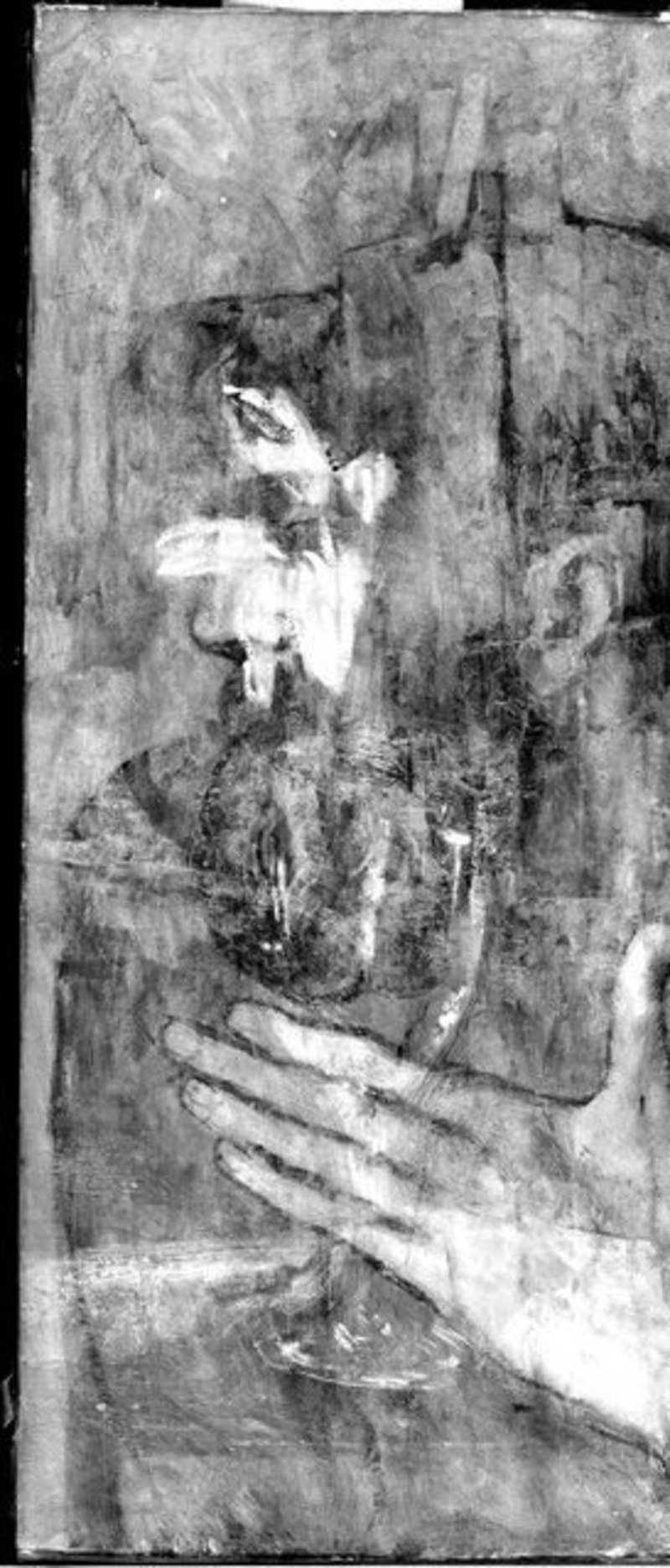

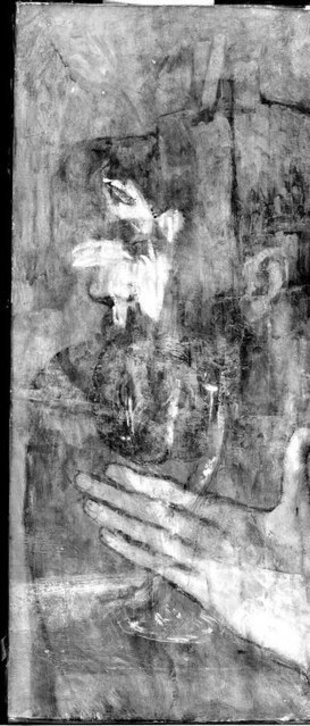

The Blue Glass from 1903 is another luminous case of this internal mutation. This piece holds not one but two underlying paintings from previous iconographies. The famous Portrait of Jaume Sabartés with ruff and cap (1901) also hid a lot of secrets that digital technology has now revealed.

“We’ll have to keep researching,” says Jimenez, who praises the chance to work alongside other institutions in finding and researching the hidden picassos. On this project, the Catalan art museum worked closely with the National Gallery of Art in Washington in the US, the Istituto di Fisica Applicata Nello Carrara in Florence, Italy, and the University of Barcelona. In fact, one of the highlights of the Blue Project exhibition are the short videos that provide a summary of the complex processes that were used to discover the hidden treasures below the surfaces of the paintings.

And there is one more incentive to visit the exhibition: it also features the last picasso of this period to become part of one of the country’s public collections, the drawing The Blind Man (1903), which Barcelona City Council bought last autumn.

art exhibition