Every drop counts

The recent rain has brought a respite to the unusual winter drought. However, the threat is a latent one and Catalonia is now in a state of pre-alert that should make us think about how to manage water in the current climate emergency

If the rains do not continue this spring, Catalonia may be in a situation of drought by the summer. Alarms have been raised this winter: despite the recent rain, water reserves are below 55%, not a favourable scenario if we consider that they were above 80% in March last year. Prior to the rain, sources at the Department for Climate Action, Food and Rural Affairs said they were “not worried or alarmed”. Yet the Special Drought Plan was activated in February, which, although not involving widespread restrictions, did entail preparatory measures for internal organisation and communicating water saving improvements to the public. The recent showers may have stopped the drought, but it is clear that it remains a latent threat.

A very dry 2021

Last year was very dry and warm all over Catalonia. Some observatories, such as the Fabra Observatory in Barcelona, registered it as one of the driest in a century. However, we did not suffer a water shortage because the reservoirs were well stocked from the rainfall in 2020, which was wet from the start due to Storm Gloria. This is one of the characteristics of the Mediterranean climate: recurring episodes of alternating rain and drought. In addition, geographical diversity means that temperatures are very different in one place to another in the same region. An example: on Sunday March 6, the average temperature in Barcelona’s port was 10.5 °C, while in Boí it was -8.6 °C. The same is true with rain: to give Storm Gloria as another example. On January 22, 2020, 100 mm of water fell per month in Falset (Priorat), while in Mont-roig del Camp (Baix Camp) the figure was only 8 mm (the two towns are separated by a distance of about 30 kilometres).

More heat

The irregular Mediterranean climate is nothing new. Yet all the predicted scenarios in the climate emergency indicate that thermometers will rise significantly in the coming decades – by as much as 2 °C - due to global warming. As for rain, it is not clear what might happen in Catalonia, due to its intrinsic variability, but there are indications that there will probably be more storms, leaving longer periods of drought in between.

As mentioned, 2021 was very dry and although winter promised rain at the beginning – there was heavy precipitation in the Pyrenees – it turned out to be disastrous: in most of the Catalan counties it rained less than 30% of the average in January.

“We hadn’t had much rain since the end of 2020, in fact. Generally speaking, during that period it had rained only 50% of what would be considered the norm. And if we think about the last few months, I would describe the situation as disastrous in 90% of the region,” said David Muñoz, a member of the Adenc environmental organisation and amateur meteorologist. A lack of rain accompanied by strong sunshine had caused a very severe surface drought.

“In Sant Llorenç del Munt i l’Obac natural park, for example, I’ve seen very dry oak trees, and I attribute this directly to the drought of recent months,” added Muñoz, who like many people is concerned about what might happen this spring. “Two things may have happened by June: either it will have rained and we no longer worry about it, or it won’t rain enough and we will continue to hear news about the drought. Let’s hope we have a couple of good downpours and it’s the former,” he says.

In sum, the problem is that while we have enjoyed the good weather of such a mild winter with many hours of sunshine, the continued lack of rainfall has gradually led to a lack of flow in the rivers and has therefore also decreased the refilling of aquifers reservoirs. The rains of recent days have only served to slightly improve the situation. According to Catalan government data, water reserves in the Ter - the Llobregat system, which is the most important since it serves most of the Catalan population - are at 54%. “It’s a situation or scenario that we refer to as pre-alert, where it’s not yet necessary to take restrictive measures, but preventive ones are needed to stop the situation from getting worse. This would include, for example, very careful management of reserves and control of demand, especially for large-scale consumers, and activating desalinated water production,” according to sources from the Department of Climate Action. At the moment, the desalination plants are operating at 85% of their total capacity, when in a normal situation they would be at 10-15%. Catalonia has two desalination plants, the one in Blanes, at the mouth of the Tordera river, which was opened in 2002, and the one in El Prat, at the mouth of the Llobregat river, which was opened in the summer of 2009 after the historical drought that marked a turning point for the country. At the time, the climate emergency was not yet fully accepted, but it made more people aware that water is a scarce commodity.

The 2008 drought

To get an idea of what this meant to Catalonia, we need only cite a few relevant facts: fifteen consecutive months without rainfall at the headwaters of rivers, both in the inland basins of Catalonia and in the Catalan basins of the Ebre river; water reserves in the Ter and Llobregat reservoirs falling to 20% of their capacity; the main Catalan aquifers hitting historic lows, and more than 4,400 news items published about the drought during the months of April and May 2008.

It will also be remembered for the then environment secretary, Francesc Baltasar, announcing that he had asked La Moreneta – the Virgin Mary statue in Montserrat monastery - to make it rain, despite declaring himself an agnostic. The prayer was held at the monastery in March during a funeral, he explained to the press in April, and in May the expected rains occurred, just as ships of the Tarragona water company EMATSA began to arrive in Barcelona loaded with water.

Religious anecdotes aside, the management measures required by that unprecedented drought - the international media reproduced images of ships bringing drinking water to the port of Barcelona, an inconceivable event in a major European capital – left a mark. Facilities such as the El Prat desalination plant were accelerated and a large-scale information campaign was also implemented to promote water-saving at all levels. In fact, it is now considered the first major environmental awareness effort, before the climate issue began making a harder impression on everyday life. The public reaction in the metropolitan area of Barcelona was spectacular, with a water saving of 20% at the most critical times.

Who consumes most water?

According to data collected by the Catalan Water Agency and published in its review of the management plan for the river basin district of Catalonia, 72.2% of the water used in the whole region is destined to agriculture; 8.8% to the industrial, commercial and service sectors; 1.3% to livestock; 11.6% to domestic use; and 6.1% to municipal and other unregistered uses, such as leaks.

However, these percentages vary significantly if the two Catalan river basins are taken separately: that is, the internal basin, with the rivers that flow into Catalan territory (Llobregat, Ter, Muga, Daró, Fluvià, Francolí, Foix, Besòs, Gaià, Tordera and Riudecanyes), and the Catalan basins of the river Ebre. In the latter, more water is destined for agricultural irrigation, as much as 94.4%, while in the former this figure is 34.6%. The difference is also significant if we look at the percentage of water destined for purely domestic consumption: 28.7% of water from the inland basins and 1.5% from those of the Ebre.

This should come as no surprise: a large part of Catalonia is agricultural, and another is urban and industrialised, and this affects water resources and their availability. Thus, 92% of the Catalan population is concentrated in the area of the inland basins, which has only 40% of the available water resources. And it is precisely these resources, which are managed by the Catalan Water Agency, that are diminished and most affected by this drought. Two reservoirs can be used as a reference to illustrate this. The one in Sau was at 47.95% of its capacity in February (82.45% a year ago), while the one in Riba-roja d’Ebre was at 92.11% (70.29% last year). This does not mean, however, that there is too much water in the Ebre, nor does it simply indicate that the country’s water management is extremely complex because the resources depend on increasingly variable rainfall.

More pressure on systems

“The less water we have, the more complicated it is to manage. We know that weather extremes will increase: it will probably not rain less, but it will be different. We will have an intense drought for longer. And then maybe all the water in the world will fall in two days and we won’t be able to deal with it or take advantage of it,” explains Sergi Sabater, professor at the University of Girona and researcher at the Catalan Institute for Water Research (ICRA). He adds that the big problem is that we just want and need a lot more water in the summer, which is when there is a higher risk of drought if it has not rained enough in the previous months. “Everyone wants to shower three times a day because it’s hot, we have to water gardens and fill swimming pools, and we have tourism, which also uses up a lot of water,” he notes.

Sabater emphasises the factor of human pressure, which pushes flows to the limit. “To give an example, when you walk through the Gironès and La Selva areas, you see a harmonious and beautiful agricultural landscape, but all of this is at the expense of having a highly burdened hydrological system. The river Onyar has always presented problems. There are sections without water or with water that doesn’t flow and is polluted. And if you ask old people in the area, they tell you of sections where in the past you could bathe and fish. And many people think that this current delicate situation is only due to climate change, they’re not aware of human intervention.”

This is precisely what happened when he spoke to the owner of a large, successful farm, who attributed the lack of water in the river to the weather and not to the use being made of it.

“We’re growing, which is very good, but we’re not aware of the consequences of this growth,” Sabater says. “We have to keep in mind that as a population there are a lot of us and we’re putting more and more pressure on the rivers, and on top of that, there isn’t much rain. If we don’t change some of the terms in this equation, the rivers will get worse. For all the water treatment plants we build, no matter how much treatment we do, it’s not enough,” the researcher adds.

ICRA has three lines of work related to water. On the one hand, it focuses on resources and ecosystems. Secondly, it works on the chemical, microbiological and toxicological quality of water (one of its tasks has been to coordinate analyses of the SARS-CoV-2 Wastewater Monitoring Network, to give an indicator of the spread of the pandemic). And finally, the area of technology applied to optimising resources, energy efficiency and cost reduction in the processes that carry water from rivers to consumption.

Technology

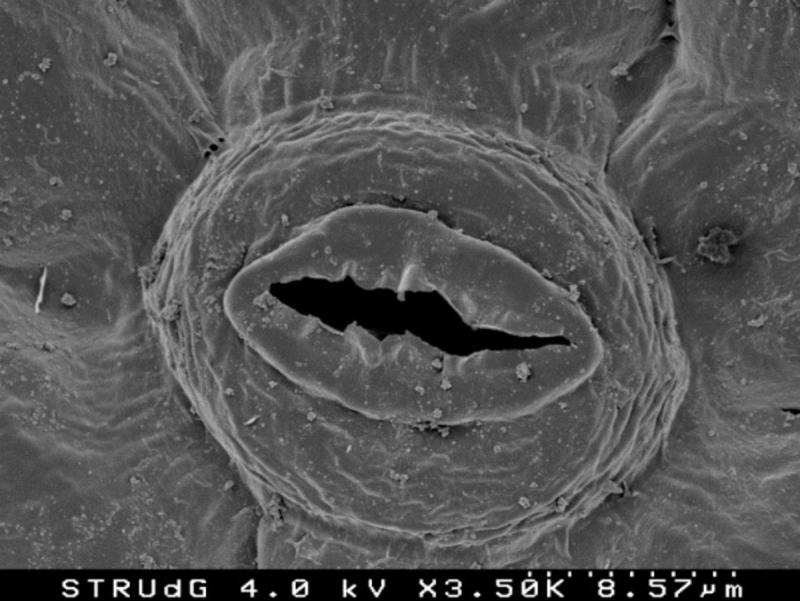

In this scenario where drought is a latent threat, technology related to water saving and its reuse is vital. “The problem with having little water is that everything accumulates in it, so we have to be able to manage it well to guarantee healthy consumption. It’s believed that when the water from the Llobregat river reaches Barcelona, it’s already passed through three toilets. In other words, it’s been used and purified three times. That shouldn’t surprise us. Instead, we should learn from countries like Israel, which are leaders in reuse. They’ve developed cutting-edge technologies and also have very advanced legislation,” Sabater explains. In Spain, the legislation is more restrictive, and the use of regenerated water – which is obtained from treatment after purification – can be used for irrigation, industry or environmental use, but not for human consumption. Most of it is returned to the environment, and in recent years regenerated water has been used, for example, to improve the flow of the river Llobregat and to stop the salinisation of its aquifers. According to ACA data, 53.3 hm³ of regenerated water were used during 2021, compared to 39.3 hm³ the previous year, so there is a strong trend to reuse this resource as the technology improves. However, a commitment to regenerating water presents the problem of geographical distribution. The largest producers of wastewater that can be treated are big cities, which are separated by significant distances from places where this water can be reused to irrigate crops or improve ecosystems. And that means high costs.

Diversifying

However, solutions are already being considered. Last February, the organisations Engineers Without Borders, Ecologists in Action and Water is Life presented the study Water and Climate Emergency in the Barcelona Metropolitan Area (AMB). The aim of this research is to diversify measures to obtain new water resources beyond large infrastructure, such as desalination plants, which need a lot of energy to operate. One option is to make the most of rainwater by building tanks so that it can be stored before it goes into the sewer system, where it will become too contaminated. According to this study, up to 80% of rainwater could be used in the AMB, whereas only 5% is currently used.

According to the above organisations, recovering aquifers and renaturalising rivers and cities are other options for diversification, so as not to have to rely on the water of the future only from large treatment facilities. This will also prevent the rise in water bills under the pretext of raising energy prices. In fact, Agbar has proposed a 7.4% increase in tariffs in 2022, although it has not yet been approved and Barcelona City Council clearly opposes the measure. It is worth remembering that Agbar controls 70% of Aigües de Barcelona, which is the supplier of 23 municipalities in the metropolitan area. Although considered a public asset, the management of water that reaches Catalan homes is still mostly private, so it is used commercially.

According to the report mentioned earlier, beyond concern for the uses of water or application of a business logic to its consumption, there is real concern over the power acquired by private companies through the system of water source concessions. “Some corporations accumulate rights over collection points, some of which were granted during the Franco era and under the auspices of rules and criteria that do not meet the challenges or needs of the current scenario of climate emergency,” the report’s authors say.

Another cause for concern is that it is in times of drought that the government proposes short-term solutions that could have environmental consequences. “We’re concerned that politicians want to cover immediate and urgent needs without making any predictions about the future. We’re hoping they don’t take us by surprise,” warns Andreu Escolà, representative of GEPEC-EdC, an ecological organisation that works mainly in the southern regions of Catalonia. Escolà recalls that during the drought of 2007 and 2008, the Spanish government approved an extension of the Ebre to bring water to Barcelona, a very controversial measure that ultimately stalled because it rained enough before the work began.

Escolà, together with a fellow activist, is immersed in a lawsuit in defence of the Siurana river. The complainants are the Community of Irrigators of the Riudecanyes Reservoir, a private company that has the rights to exploit the water of the river. “But only 40% of the water is used for irrigation, 60% is for the town councils,” explains Escolà. This is another step in a conflict over the water from the Siurana between the Priorat region – which loses it, leaving the river dry for most of the year - and the Baix Camp region, which consumes most of it. “Once it has passed through the treatment plants, a lot of water is discarded into the sea, when it could undergo a tertiary treatment. And in many places there’s groundwater that could also be used, but it’s polluted. Macro-farms and intensive agriculture are damaging this resource, and no one is worried about this, not even in the Department of Climate Action,” Escolà concludes.

feature Environment

feature environment

feature Environment

How much water do we use?

The costs of water services depend on each place, causing bills to vary greatly. With the cost of the water we consume, bills also include water tax, which is paid to the ACA to cover hydrological planning (infrastructure, ecological flows, pollution prevention,...). The Catalan government says the average price of domestic water in Catalonia is €2.39 per 1,000 litres. This may seem cheap, but on average every resident uses 133 litres of water a day. Here are some examples of everyday activities that use water: washing our hands uses 2 to 18 litres; brushing our teeth (2 to 12); showering (30 to 80); laundry (60 to 90); the dishwasher (18 to 30); washing dishes by hand (15 to 30); flushing the toilet (6 to 10); cleaning (10); watering 100 m² of lawn (400 litres).

Municipalities on alert

In the Alt Empordà in Girona province, some 22 towns are on alert for drought due to the decline in water levels in the Fluvià-Muga aquifer system, one of the main sources of water in a large part of the region. This has already led to restrictions on consumption, such as the watering of green areas, and a ban on filling ornamental fountains and swimming pools, among other measures. In the rest of Catalonia, many of the water supply points are on pre-alert, with the exception of the municipalities that are supplied by the Baix Ter aquifer (Baix Empordà); those of the Carme-Capellades aquifer (Anoia), and those served by the Water Consortium of Tarragona. This is the case for inland basins, with reservoirs at 53% capacity. The reservoirs of the Ebre Hydrographic Confederation are a little better, at 56%.