The Curse of Civil War Loss

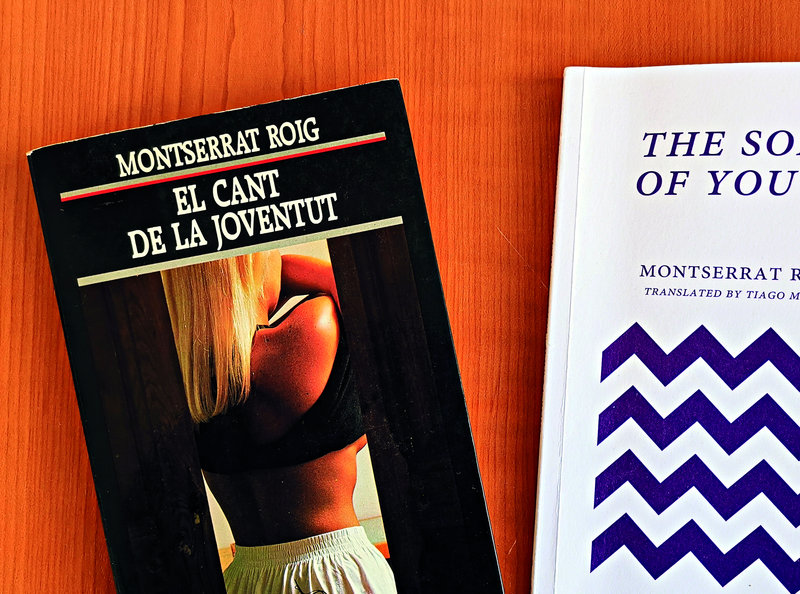

The Song of Youth is the translation of Montserrat Roig’s last work of fiction, the eight stories of El cant de la joventut (1989). Despite her fame in Catalonia, this is the very first book of hers to be published in English. Congratulations to Fum d’Estampa! It’s a great choice, with Roig in full flight, at the height of her powers

The title story is magnificent. An old woman is dying defiantly in hospital. She hates the thoughtless way the nurse patronises her and how the doctor scurries away as soon as possible. She uses language, all she has left as her body fails, to defend herself. The old woman confined to her bed remembers a love affair during the Civil War. In a ferocious climax, Roig combines love and death: the woman loses control of herself in both. The story is a passionate cry to respect the old and a lament for ageing.

The stories are brief, with two exceptions, Mar and Before I Deserve Oblivion. The mysterious and complex Mar is a tale of love, loss and loneliness between two women. Love and Ashes is also about friendship between women. Free from War and Wave is a chilling Civil War anecdote. It contains stupid, needless death at the front, but more vivid is the constant struggle of women at home. Division is a political satire against an influential politician making sexual insinuations to his hostess, Glòria. In characteristic Roig style, the story is not just about sexism and abuse of power, but is enriched by Glòria’s uncertain relationship with her husband after the death of a child. The Chosen Apple, like the title story, is about death, but here a man is dying at home and loved. In the long Before I Deserve Oblivion, Roig draws parallels between a censor and a Peeping Tom. A Francoist censor fantasises about the sex scenes he is crossing out from submitted fiction with his blue pencil. Now in democracy, he is a school-teacher caught hiding in a cupboard to watch school-girls undressing for gym class. This “ridiculous man” tries to dress up this sordid behaviour with a poem by Cavafy on longing and desire.

Deep Feeling

The shortest story in the collection, I don’t Understand Salmon, shows with eloquence and precision some of Montserrat Roig’s qualities and themes. If, let’s say, a sophisticated short story has two threads (or places or times) coiling round each other (like this collection’s title story), I don’t Understand Salmon has three in four pages. Norma is visiting a site in France where Spanish Civil War dead are being honoured, their graves cleaned and marked, the undergrowth cut back. Her child is asking her why salmon surge up the river to die in the place they were born: the opposite of these long-dead refugees who died far from their land. The conversation of mother and child alternates with the description of the cold day at the graves. In other simultaneous conversations, an old Republican is telling Norma about his torture at Mauthausen concentration camp; and another deportee, Lluïsa, recalls how bodies were being washed up on the beach at Argelès a week after being swept down a river and out to sea. Some of the salmon die too, smashed on the rocks, swimming against the current. “Oh, those poor salmon,” the child says. As she listens to the previous generation’s testimony, Norma is determined not to pass on the curse of Civil War loss to the next generation. The three themes - salmon, Republican graves and Mauthausen - intertwine with emotional force.

The above paragraph may make it appear that Roig is writing a story as if it were a thesis. Given her political commitment, there is often something of thesis in her fiction. These are stories (like her novels) of ideas. However, the ideas do not diminish the literary qualities. On the contrary, it is these that bring the ideas to life. Her prose is lyrical, based on clear description of scenes and feelings. At first glance there is nothing complicated about the stories. Her writing has a bright sheen. The second glance shows she is writing of murder and unbearable suffering. Her luminous surface covers deep emotion and history.

To translate a book like this must be hard, given Roig’s care with words in these very intense stories. Tiago Miller meets the challenge. He is not frightened to translate freely. The result reads well and is a long-awaited introduction in English to this fine novelist.

book review

A Full Life

It is still a shock reverberating around the background of Catalonia’s cultural world that Montserrat Roig (1945-1991), the liveliest literary figure of her generation, should die so young and so suddenly of cancer. Yet she achieved more in those years than most people who live twice as long.

As well as five novels, Roig wrote an account of the siege of Leningrad (L’agulla daurade, The Golden Needle, 1985) and her remarkable 900-page Els catalans als camps nazis (1977), which took several years of research. Based on fifty interviews with survivors of the camps, especially Mauthausen, and published in the year of the end of the dictatorship, it remembers and honours the Catalans exiled by the Civil War and then deported. The book challenged a Catalonia emerging from the dictatorship to recover the values of the Republic and the crushed memory of the Franco decades.

Feminist rebel

Her first book was Molta roba i poc sabó (Lots of Clothing and Little Soap, 1970), stories that prefigure her trilogy on two families of Barcelona’s Eixample: Ramona adéu (Goodbye, Ramona, 1972, to be published in English by Fum d’Estampa later this year); her best-known novel, the Sant Jordi prize-winning El temps de les cireres (Cherry Time, 1977); and L’hora violeta (The Violet Hour, 1980). The trilogy portrays the personal struggles of three generations of women in the main events of Barcelona’s twentieth century.

Feminist, communist, mother, journalist, Montserrat Roig conjured time from nowhere for a lot more than her books. She brought up two children. She wrote opinion pieces in several papers and conducted famous television interviews (some are available on YouTube): the qualities of observation and precise description in her fiction are suggestive of this journalistic training. She was a political activist, too, with the PSUC (Catalan Communist Party) during the Franco dictatorship, left the PSUC because of its dogmatism, then returned to it (she was Number 10 on the electoral list for the 1977 elections, one of only 3 women in the first 20) and left it again in 1978 when it supported the monarchy.

Montserrat Roig was a rebel. She was very much of her time, but opened her own path, a pioneer in feminism and historical memory. Her permanent legacy is her profound and shining literature.