“The longer you don’t go out, the harder it becomes”

In Japan it’s called hikikomori (being confined), but here too there are people who sometimes spend years at home without leaving

Social isolation is a growing health problem.” This is from the 2014 study, Hikikomori in Spain. Since then, the mental health specialists who did the study have published two more, the most recent last year. They analysed a good number of severe cases of isolation in Catalonia for a year. Hikikomori, they say, is a psychopathological and sociological phenomenon in which people, especially young people, withdraw completely from society for a period of at least six months.

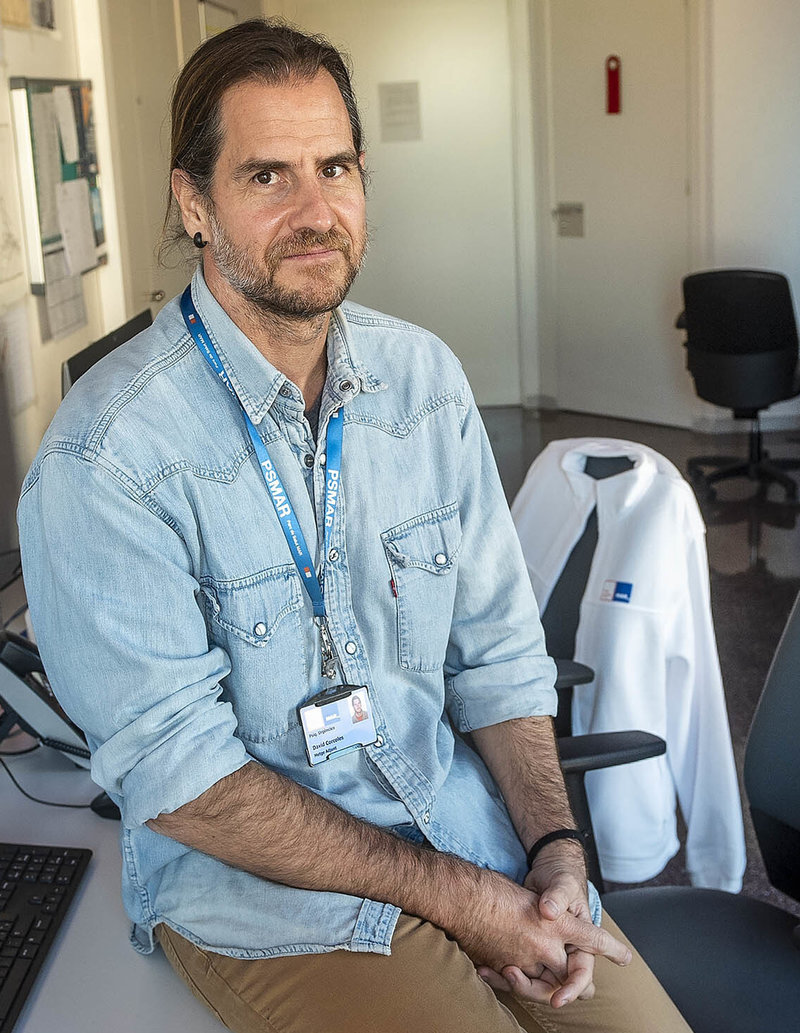

This research was based on the cases of 200 people. One professional who took part was psychiatrist David Córcoles, from the Institute of Neuropsychiatry and Addictions at Hospital del Mar. “There are people whose condition has worsened with the pandemic, such as patients with anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and agoraphobia.” In the case of agoraphobia, he adds: “An extra effort is needed, because if you already didn’t want to go out, you have just been handed a justification for staying at home. And an important fact is that we know the longer you go without leaving home, the harder it is to do so.” It can be hard to detect hikikomori if the people around you do not see it first. “We have patients who have not left home for 20 years. And one, for 35. He hasn’t left the house for any reason,” says Córcoles.

There are two types of hikikomori, primary and secondary. “In the primary there’s no pathology and isolation is the only symptom. Secondary hikikomori is caused by a mental illness.”

It is not hard to fall foul of the syndrome. Imagine a person with depression who only wants to stay in bed. They stop going out, and can continue not going out if there is no one around to help. “It fulfils the criteria of secondary hikikomori. Depression leads to confining oneself. The importance of people in the environment to detect these cases is clear,” says Córcoles, who nevertheless adds: “Of our 200 patients, we were unable to visit 36; their families did not want us to. It’s hard.”

The average person studied was around 40, with an average isolation time of three and a half years. “We found that the longer it went on, the harder it was to change the behaviour. The more serious cases justified involuntary hospitalisation. What seems contradictory, however, is these people ended up better off than those whose situation had not been so serious.”

“Everyone likes being able to decide not to go out. Yet it’s another thing when you shut yourself up at home and the day comes when you have to go out but can’t. You do not decide freely. Something is deciding for you,” adds the psychiatrist.

It is hard to imagine anyone in this situation having family responsibilities. “Some do, but not many. It might be okay if you just have a partner. I remember one case where the person affected hadn’t been out for 20 years due to agoraphobia and didn’t want any treatment. And they had a partner and a daughter,” he says.

With many sufferers unnoticed and a lack of public mental health professionals, hikikomori is underdiagnosed. “Hikikomori syndrome is a case of hidden suffering. We must also keep in mind that they are people who do not cause trouble, on the contrary. These cases are invisible.” In their studies, the research team noted: “The prevalence and magnitude of isolation have probably been underestimated due to the lack of specific community mental health services that can detect and treat these people at home.”

Some 60% had a family history of mental disorders, with 45% among close family. In 56% of cases, the mother had a history of emotional disorders. It is often the family that detects the problem, but family can also be part of the problem. The quality of family relationships, whether the family is dysfunctional, whether there has been emotional neglect or abuse, are very important.

Regarding family dysfunction in relation to hikikomori in Japan, the research talks about the concept of amae, a Japanese term that refers to the indulgent dependence of children on parents. To this type of infantilisation should be added an undemanding upbringing, leading to young people with little motivation and dependent on the comforts of the family home. This can be applied to many cases of hikikomori in Japan, but also to other societies, like our own.