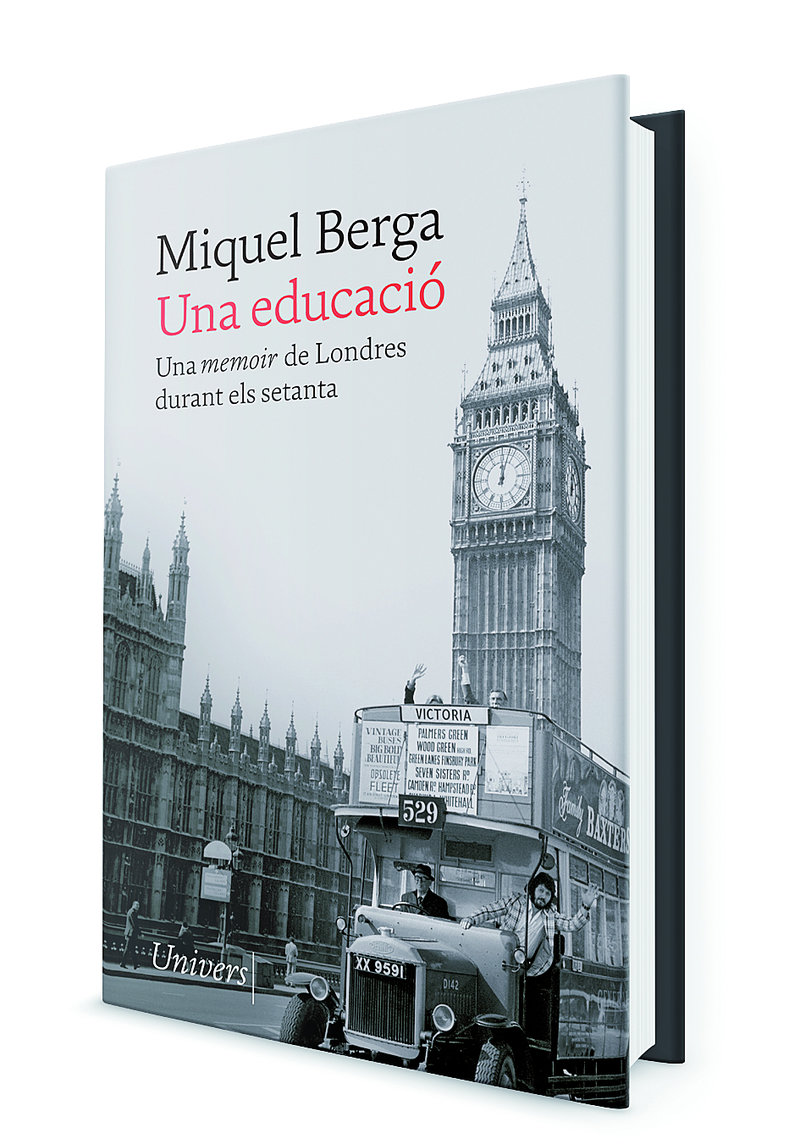

Professor of English literature at Pompeu Fabra University and a specialist in the work of George Orwell, Miquel Berga (Salt, 1952) has just published Una educació. Una ‘memoir’ de Londres durant els setanta (An Education. A memoir of London during the seventies) (Univers). It is his most personal book so far, in which he evokes his stay in the British capital – without a penny to his name and without understanding a hint of English – in the early seventies.

“In the autumn of ’72, the sixties were not yet over,” writes Berga about the atmosphere at that time in London, which acted as a pleasant refuge from the misery of the Franco dictatorship’s final years. This is the story of a young man’s first trip to London, arriving at Heathrow Airport as a stowaway on a tourist charter and ending up with a doctorate in English philology.

In just 125 pages, Berga’s exercise in recall manages to paint a portrait of an era and at the same time describe an experience that would end up shaping his professional career. What’s more, he does so with his hallmark irony and by deliberately distancing himself from the self he talks about in the book. His memories also rest on the lives of others, some 30-odd characters who would not be out of place in a work of fiction.

For someone who has written profusely about the lives of others (Orwell, Auden, Langdon-Davies...), Berga reveals a certain shyness when delving into writing about himself. He gave us some glimpses into his London experience in the preface to his book, Un aire anglès (An English Air) (Edicions del Periscopi, 2018), a collection of his columns in the Sunday edition of El Punt Avui newspaper. Fortunately, his publisher convinced him to delve deeper, and the result is a book that you read with a smile on your face until the end.

Why did you choose the term memoir to define the book?

In English, the term memoir suggests a story limited to an episode, contact with certain figures, a specific period, and so on. It seemed to me that the concept pointed more accurately to what I wanted to do and helped me get over what we might call autobiographical pretensions, which can be grandiose and sometimes shameless, aiming to give one an importance that is often a touch ridiculous. Some people write memoirs as if they were presenting their curriculum vitae... I felt that a modest memoir would be more than enough.

Calling the book “An Education”, with an indefinite article, suggests it was one of many that were possible.

Yes, we can of course value life experiences as deeply formative elements beyond what regulated teaching provides. We all know highly educated people who have little in the way of academic studies. You also have to remember that at that time everything was so precarious that being self-taught was a very reasonable option. Anyway, I started studying English philology at a Catalan university after returning from a year-long stay in London and so my experience of English was very different from that of my classmates. My English had benefited from direct experience with the actual use of the language.

Are the two quotes that open the book also a statement of intent? You quote the poets Louis MacNeice and F. S. Flint, exponents of a plain style and clarity of word.

They are just a few verses that aim to remind us that for any young person it is easy to be touched by life in a metropolis like London. It’s a kind of experience that sets you apart and that stays with you.

Does the book aim to be a portrait of an era, an evocation of a slice of life, or your idea of education, or maybe all of them at once?

I guess it ends up portraying the time, here and there, and it also suggests a way of being young that, in many ways, may never be repeated. What it’s not meant to be in any way is a teaching manual. I like to think that, above all, it’s a literary text.

Was Miquel Berga’s ’English air’ forged in London in the 1970s, or did he simply find his natural fit there?

As the reader will see, there were no big plans made in advance. But it’s clear that I felt comfortable there and I was fascinated by an atmosphere that was so different from that of Catalonia at the end of the Franco regime. Also, keep in mind that I’m from Salt, and we dwellers on the outskirts adapt easily.

“I was 20 and had two phone numbers.” This is the beginning of the story of a young man who arrives in London in the early seventies on a journey to freedom. Does it also evoke a certain freedom now lost to a generation of young people who live under the protectionism of their parents.

Yes, it’s clear that today’s conditions and youth culture do not seem conducive to the carefree attitude that was quite normal back then. Young people used to hitchhike, for example, and we were not so aware of the dangers and concerns that are very much present in the consciousness of young people and their parents today. The sentence, however, also has a function called narrative. The subject can be both me and him. It is a way of announcing a certain narrative duality that is an essential part of the book.

Chance and a painting by Bacon led you to meet John, the journalist who had written the first chronicles of the Normandy landings. And Romanian musicians, Mary Jean, the Irish drinker, the Greek friend… Miquel Berga appears as a spectator of his own stories.

The whole book is presided over, as I say, by the past/present duality, by a deliberate distancing from the he who is me. Indeed, the narrator – despite being in the first person – is busier describing others than giving way to personal introspection. Maybe by writing these stories he and I have reunited, have recognised each other, and maybe even become friends.

Regarding the chance encounter with a certain Julie – Julie Christie who starred in Doctor Zhivago – you state that “youth and ignorance are indispensable ingredients for starting an education.”

As we know, ignorance can be pathetically daring, but young people should not let this paralyse them. When I went to London without knowing a word of English and without any job prospects or money, some friends would say to me, “I’ll study English and then I’ll come” or “If you find me a job, let me know and I’ll come too.” The starting point is ignorance: over-preparation can be paralysing. One must take advantage of the right amount of irresponsibility at a time of life when most prone to it and when it’s most tolerated: youth.

The book is steeped in irony and classic English humour, but it describes harsh situations and how London became a haven for young Catalan women looking to have an abortion.

Yes, behind that air of somewhat fun adventure float, of course, the miseries of the time, which were terrible in many ways. The issue of abortions, which were totally forbidden here, generated a collective humiliation, and very hard experiences for thousands of women. In fact, in those years, the feminist struggle was at its peak in England, and the evolution of things reminds us that all social battles must be won over and over again, that every generation must win them again. The same could be said of the experience of homosexuality, which also appears in one of the chapters...

The 15 chapters or episodes in the book come across as a sort of miniseries. Do you agree?

Well, I’d like to think that there are 15 stories that can be read independently, but it is true that they are linked by the voice of the narrator and by a structure that might make you think of the series format. In more traditional terms, perhaps we could think of it as a story of growth, a sort of journey from innocence to experience, recalled with the benefit of elapsed time, more than 40 years no less!

In London you worked as an accountant and later somehow found yourself working as a journalist for Catalunya Express. You explain how you voluntarily let slip an exclusive, related to the naming of a Spanish general involved in a coup attempt.

Yes, the narrator of this book is more concerned with surviving in a city like London than with pursuing a career. It is clear that he is only a journalist by accident, and he knows it.

I thought the cast of characters who parade through the book would not be out of place in a work of fiction.

They are all real people, although many have false names, and in such a short book there are about 30 of them. There’s a desire on the part of the narrator to portray himself by portraying the people he knows. Maybe that’s why we are said to be the stories we tell. I mean our identity is shaped by the stories we tell about ourselves and, above all, about others. We are nothing without others.

You have written biographies, books of essays, translations and journalistic articles. What about a novel?

I’ve never really thought about it. I have the impression that plenty of novels have already been written, and perhaps not all of them were essential... Life seems a sufficiently entertaining and mysterious affair and I don’t know if it’s necessary to invent parallel fictions to add to the obvious hallucination of it all.

books interview

books interview