The end of corsets

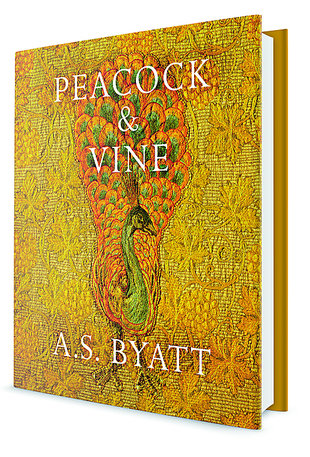

Antonia Byatt’s meditation on Marià Fortuny i Madrazo and William Morris compares two artists of huge energy in several fields. They were of different generations, different countries, different life-styles, different ideology. What they had in common was a “coming together of life, work and art” (p.28).

Their work was design in a whole number of arts and crafts: textiles, painting, sculpting, dyeing. Their houses reveal the two artists. Each worked where they lived and the house was the total work of art, drawing together all their passions and disciplines. Byatt was familiar with the British writer, socialist and fabric designer William Morris’s famous houses at Kelmscott and in London, where he attempted to create communities of creative workers. She found Fortuny’s palazzo in Venice - and it is Fortuny who is the subject of this review.

Duchesses’ Dresses

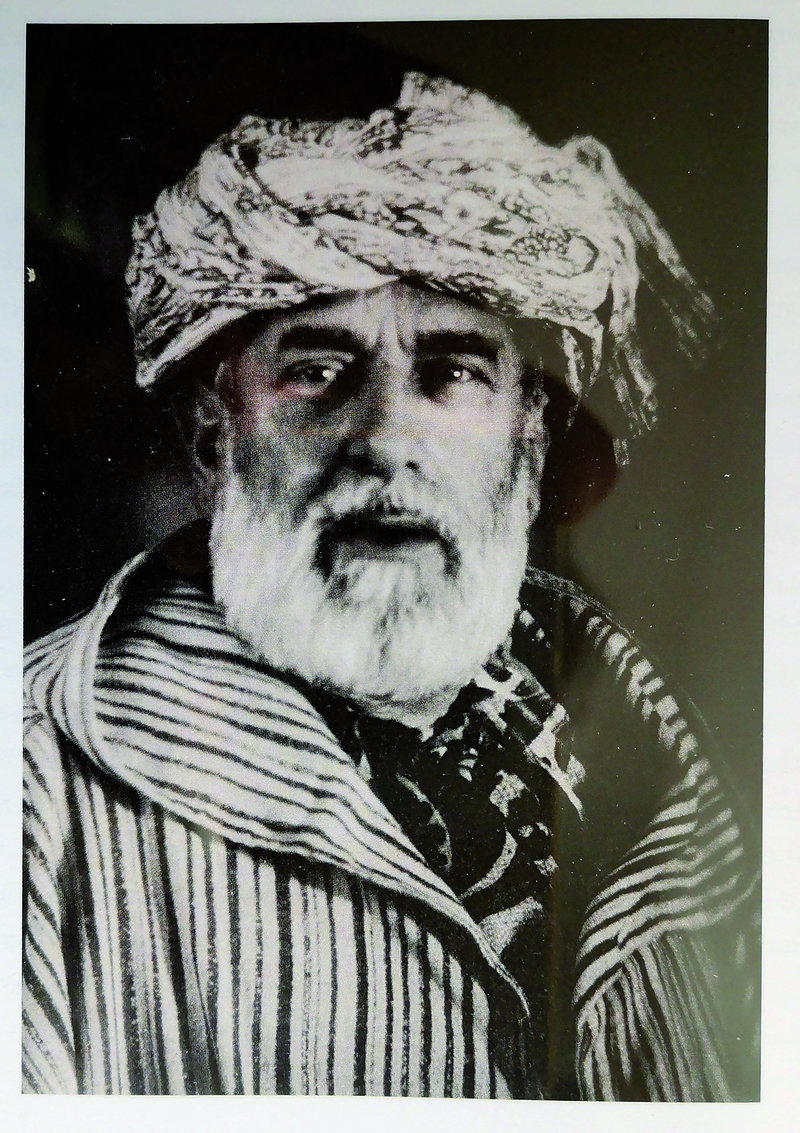

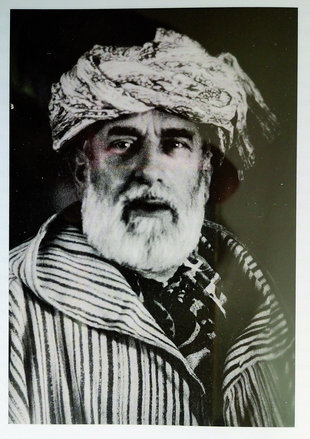

Marià Fortuny (1871-1949), or Mariano Fortuny as he was known and called himself, was born 150 years ago. Fortuny was in his day a famous multi-faceted artist and dress designer. He was born into artistic royalty, for his father was the painter Marià Fortuny i Marçal from Reus, who died of malaria in 1874 at the age of just 36, and his mother Cecilia de Madrazo was a pianist and collector of ancient textiles. Fortuny i Marçal’s father, also a painter, became director of the Prado Museum in Madrid.

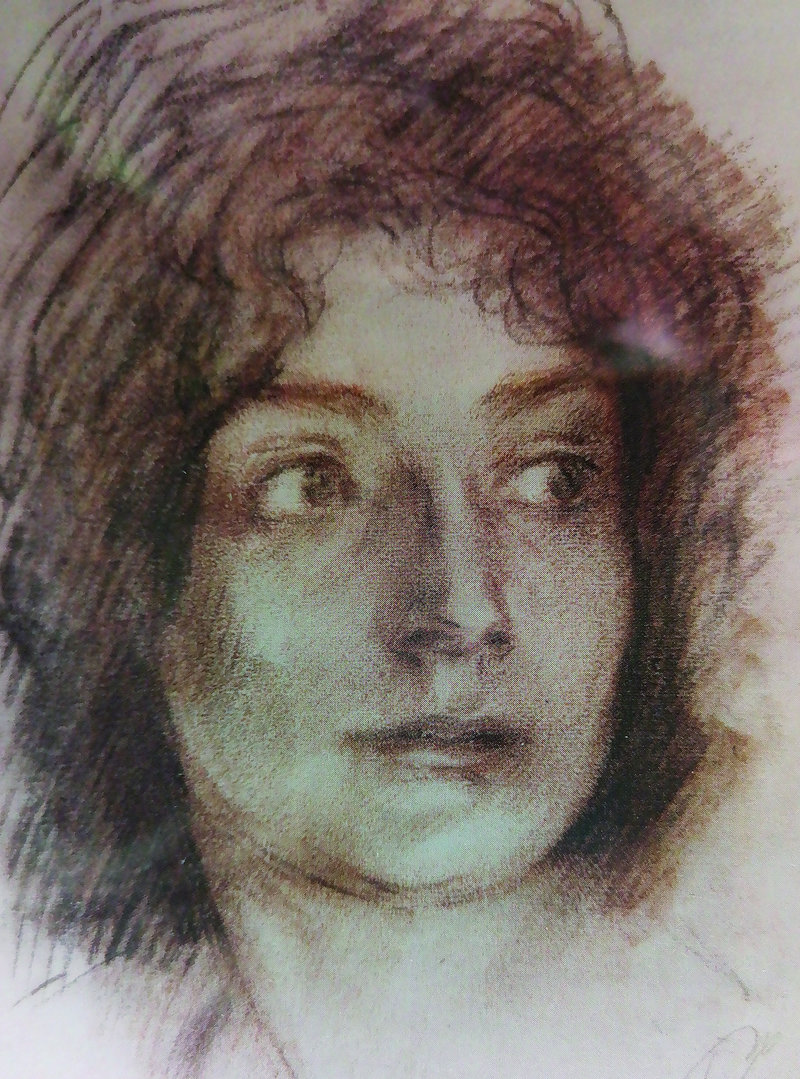

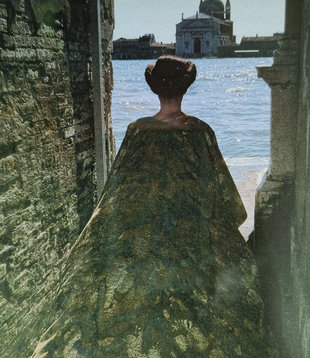

Fortuny i Marçal was known for his orientalist canvases. In the 1880s, after his death, his paintings of turbaned Arabs, rumpled tapestries and half-naked women were all the rage throughout Europe. They sold for small fortunes, leaving his widow Cecilia and their children without money worries. The family moved to Paris and then, in 1889, to Venice, as Marià was (supposedly) allergic to horses. The family established themselves in a few rooms of the enormous Palazzo Pesaro degli Orfei. Here Fortuny lived and worked for the rest of his life, buying up more and more parts of the mansion. Today it is the Fortuny Museum. In 1902 the French artist Henriette Negrin came to live and work with him. The couple stayed intimately together till his death. They lived an intense story of artistic exploration, invention and commercial success.

Fortuny was an artist in a great many fields. Photography was a passion: he travelled to Egypt and Greece to study dyes and clothing, taking pictures all the time. He patented various devices for improving theatre lighting. He painted, drew, engraved and sculpted. He collected metals like his father and textiles like his mother. But Fortuny is best remembered for his scarves and dresses, his fashion designs based on the flowing robes of Ancient Greece. And it is not altogether surprising that, as Byatt tells us, he is the only real person to be mentioned in Proust’s Remembrance of Time Past, since the book’s duchesses and courtesans got through a great many dresses.

Swaying bodies

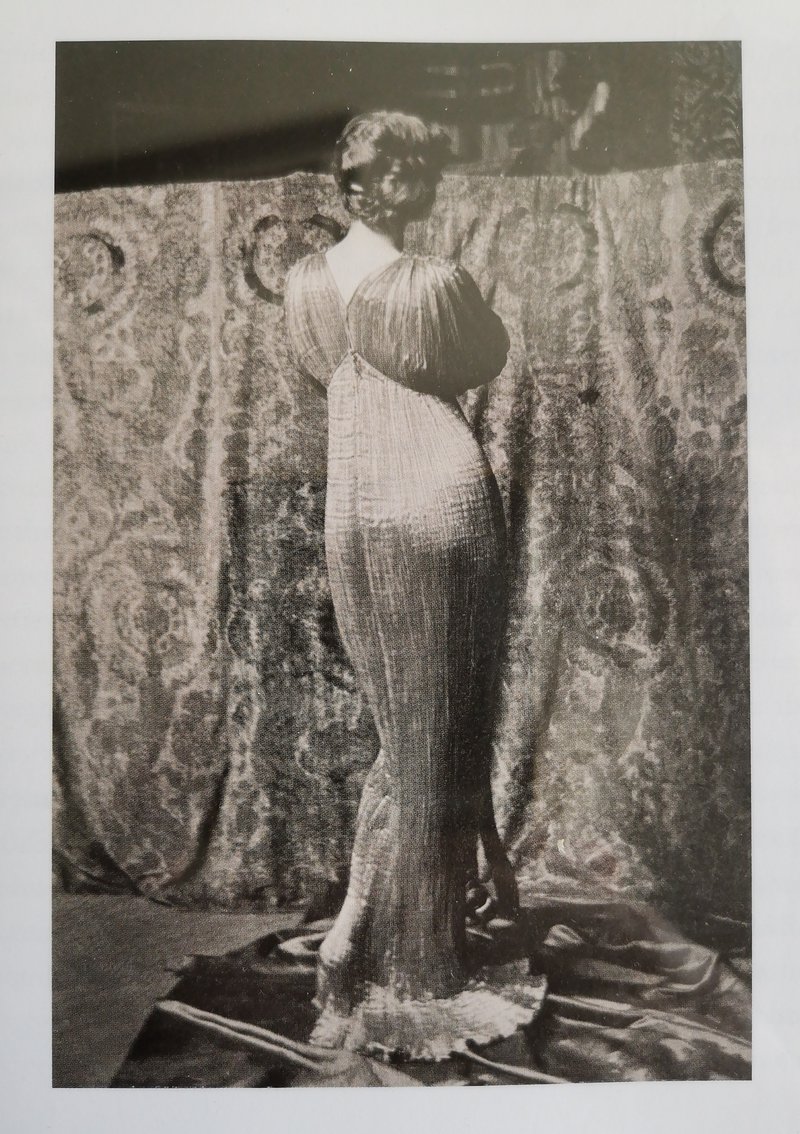

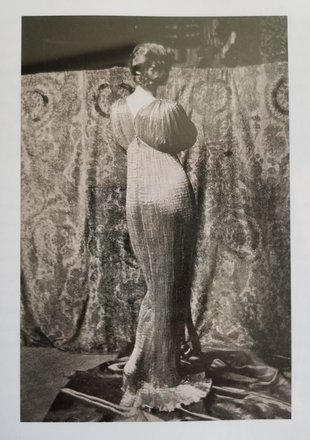

The most famous is the 1909 Delphos dress, probably designed by Henriette: their work was as entwined as the grape vines that twist across many of their clothes, though it is Fortuny’s name that has lasted. The Delphos was a long sheath with pleats (Henriette designed the machine for making the pleats), “worn over naked flesh or over a silk shift” (p.116). These simple but glamorous sheaths freed women from the corsets of the Victorian age. They were comfortable. Near-transparent, moulding to any size or shape of body, they were daring and sensuous, though curiously Byatt says they were not at all sexy.

The Delphos is exquisite in its simplicity, but more usually Henriette and Fortuny designed dresses with complex patterns - in this, like William Morris’ wallpapers and tapestries - and colours, experimenting with dyes. Their dresses were designed with moving bodies in mind. Peacocks and pomegranate trees might be printed on the bright silk and the birds and fruit swayed on the branches as the woman walked. The colours too might change with the day’s changing light. The dresses were often held together by subtly shaded Venetian beads. When, in Proust’s masterpiece, Albertine finally leaves Marcel, she takes none of the luxuries he has bought her except one item -- a Fortuny cloak. When Susan Sontag died in 2004, she was buried in a Fortuny dress. Fortuny and Henriette’s fashion house was big business: at one stage they employed 100 people on the second floor of the palazzo, cutting, stitching, pleating, dyeing and ironing.

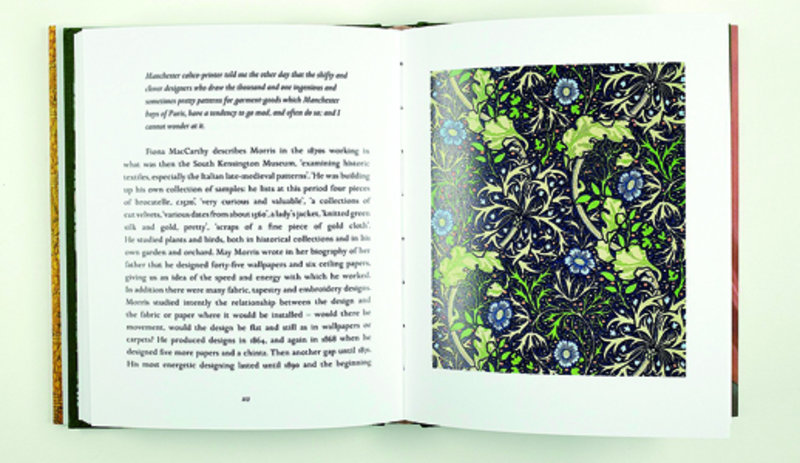

Byatt spent many hours in the Fortuny museum, drinking in the elegance: “Silks and velvets never the same colour twice” (p.164). In the couple’s Venetian home, she could see how they fulfilled Morris’ famous tenet that everything in a house should be functional or beautiful. The book she has written is a beautiful object in itself, full of exquisite photos of Venice, of dresses, of Morris’s and Fortuny’s patterns and dyes. And she has managed the difficult task of describing and explaining in words these brilliant artists’ work.

book review

book review

Self-conscious realism

A.S. Byatt, born in 1935, is still writing the novels she is known for, as well as books of literary criticism (on Wordsworth and Iris Murdoch, among others). A famous encounter at a literary event in the late 1960s helps define Byatt’s writing. The novelist Angela Carter insulted her: “The sort of thing you and your sister are doing is no good at all.” While Carter was inventing alternative worlds in luscious language and increasingly wild flights of imagination, closer to science fiction than realism, Byatt and her sister Margaret Drabble were writing more traditional novels. Byatt recognised the difference and called her own work “self-conscious realism”, self-conscious because she was integrating more modern literary techniques into nineteenth-century realism.

Dramatic realism

This definition applies to Byatt’s series of four novels threaded round the life of Frederica Potter from the early 1950s to the 1970s, a dramatic portrait of shifting personal relationships in a changing Britain. Her big, later novels, Possession (winner of the Booker prize in 1990) and The Children’s Book (2009) are realist, too, but the word is inadequate to describe books that are both erudite and highly passionate. Byatt is a novelist of ideas, like her forerunner George Eliot, while also exploring desire and sex. Angela Carter might even have appreciated their ambition.

Fortuny and Morris fit into the Victorian and Edwardian worlds that Byatt investigates in these two novels. Morris was a powerful artist in many fields and a restless thinker, drawn to revolutionary socialism in later life. And Morris leads to Marià Fortuny, so different, yet they are similar in their energy, the diversity of their artistic endeavours and passions for art and colour.