Independent woman in a hostile world

Forty Lost Years is an unsentimental novel with direct and clear prose. Its first-person narrator, Laura Vidal, is a timid working-class girl struggling to find herself. Then, gloriously, she grows to live free of subordination to any man or conventional ideology

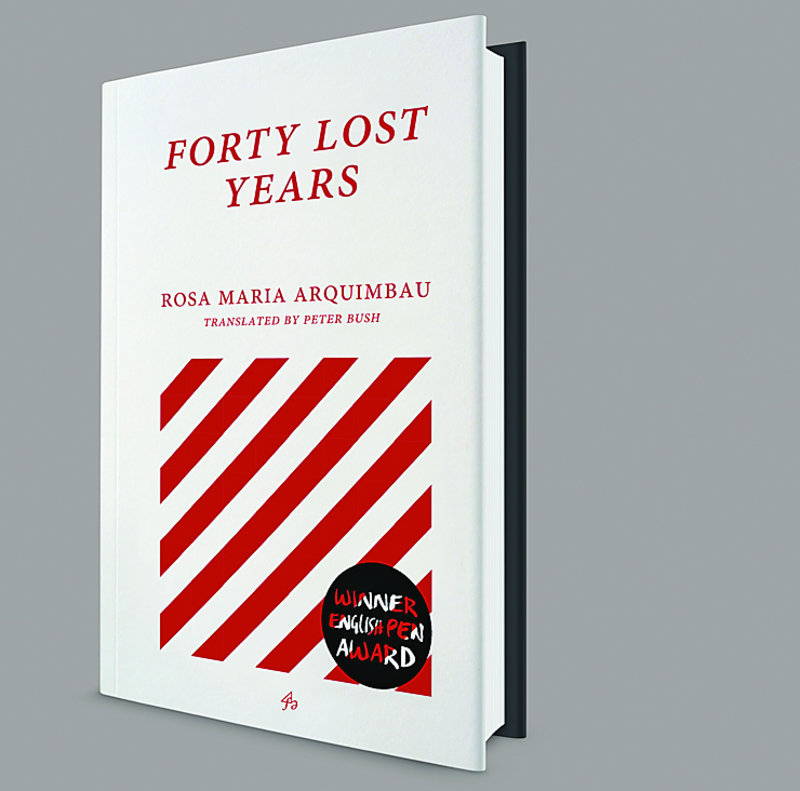

Forty Lost Years came out in Catalan in 1971 - 50 years ago. The ferocity of the dictatorship was by that time mainly reserved for political activists. Though censorship was still strong, it was possible to publish in Catalan even a leftist, feminist novel like Arquimbau’s. Now this partially forgotten classic has been translated by Fum d’Estampa, an adventurous, new publisher of Catalan literature in English (an interview with its co-founder Douglas Suttle featured in the July 2020 Catalonia Today).

Freedom in the Republic

Forty Lost Years opens with Laura aged 14 in April 1931, on the day the Monarchy falls. She and her best friend Herminia run through the flags and cheering crowds to inhale the freedom of the new Catalan Republic. Arquimbau follows Laura through the Republic, when women attained certain legal rights such as divorce and limited suffrage and enjoyed greater sexual and social freedom. Laura’s early hopes are then dashed by Civil War defeat, exile in France and Algeria, and then three decades of dictatorship. The forty lost years.

History books report political speeches, wars and revolutions, whereas a novel like this shows what life felt like for one of the majority with no special interest in politics. Though Laura and her friends are not portrayed as activists in the novel, they are well aware that the Republic offers a different future. Political events are seen through their impact on personal lives: for example, Laura is due to meet a lover, but it is impossible because of the October 1934 General Strike. In the same strike, her best friend Herminia’s brother is killed. Arquimbau focuses not on the street fighting, but on the devastating scene of grief in Herminia’s family’s flat.

Forty Lost Years is a detailed record of lost times. It is much more than the evocation of the past, though. The novel is structured through contrasts of the fortunes and attitudes of several women. Laura’s friend Engràcia finds a rich lover to buy her luxuries. Engràcia’s attitude is to use sex to screw money out of men. Herminia has the conventional romantic dream of falling in love, getting married and having three children. Laura’s mother is resigned to a life of drudgery. She is the caretaker scrubbing floors in a block of flats, where she, her husband, a CNT woodworker unable to afford the furniture he makes, and their two children live in a “cubbyhole” beneath the stairs.

Sex not Love

Laura becomes a seamstress, apprenticed to a dressmaker, one of the few jobs allowing young women a certain freedom. She discovers that she too, spurred on by Engracia’s example, can attract men. She becomes the lover of Tomàs, a “posh slob I bent at will” who is quite happy to “shell out” for sexual favours. Laura is different from her friends: unlike Herminia, she doesn’t believe in love; but unlike Engràcia, she is not cynical. She uses Tomàs’s money to both help her family and set up her own dressmaking business. Women, she thinks, are trapped by ideas of romantic love. Sex for Laura is to buy independence, not fancy goods. The key to women’s independence is to have your own money, as all strands of feminism recognise. But many modern feminists might find Laura’s cold clear-headedness hard to take, basically because she sells her body to a man she doesn’t like to get the money to set up in business.

“Laura, be sensible. Be a good girl,” Herminia urges her. But the defiant Laura thinks:

I’d already chosen a different style of life. I’d followed Engràcia and kicked over the traces. And, hell, I wasn’t hurting anyone. At most I was hurting myself and I couldn’t care less about that. (p.58)

Arquimbau is not simplistic. Laura wins her independence, becoming under Francoism a dressmaker for the wealthy, but she loses too. At times she feels disgusted with herself and, as someone running so strongly against conventional love and marriage in an age of repression, she pays a price of loneliness for her single-mindedness.

This is a wonderful novel. Arquimbau (and Peter Bush’s translation) catches the direct, ingenuous language of a girl who grows to value herself as a woman in a hostile world. Too intelligent and sharp-tongued to make friends – yet every cutting remark is true –, Laura carves a solitary path through war and dictatorship.

book review

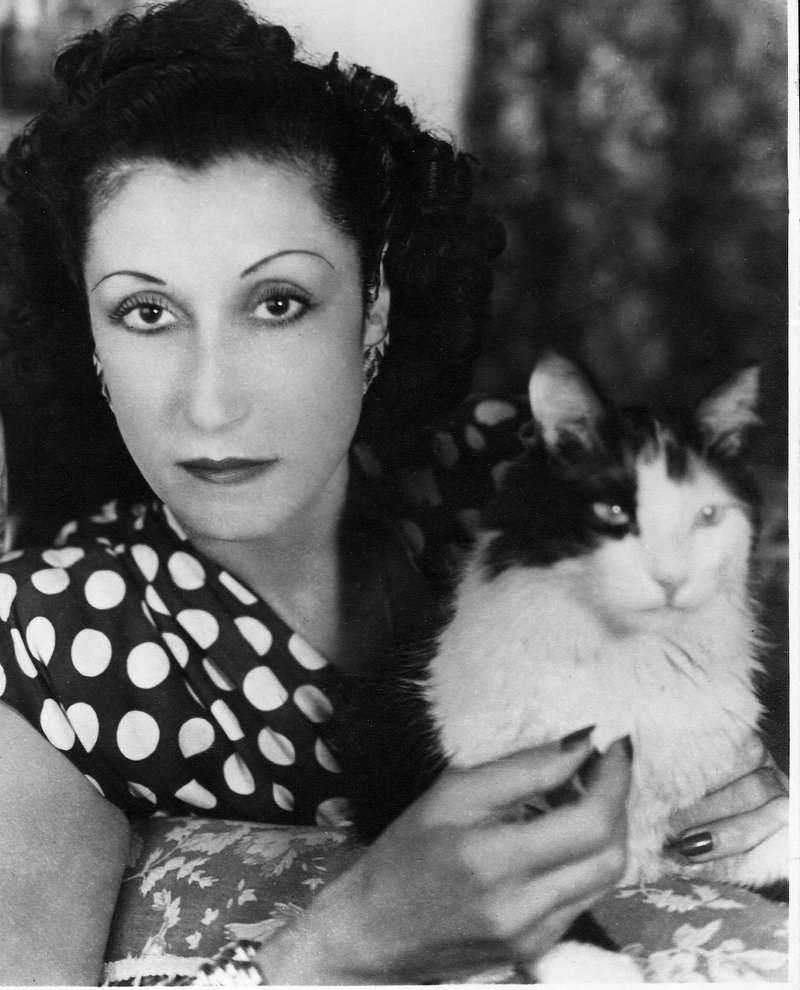

Feminist revolutionary

Born in Barcelona, Rosa Maria Arquimbau (1908-1992) started to write at a very young age. Between 1924 and 1938, she worked as a journalist and columnist on several papers and journals. There were a lot of these: in 1933, according to Albert Balcells, there were a remarkable 25 daily papers published in Catalan. The young Arquimbau became a well-known figure, also writing plays and stories, published sometimes under the name of Rosa de Sant Jordi. Maria la roja, a success in 1938, was one of five performed and published plays.

The critic Julià Guillamon - author of L’enigma Arquimbau - has recovered Arquimbau’s texts and investigated her life in recent years. Through him, Comanegra re-published Quaranta anys perduts in 2016, along with the stories in Història d’una noia i vint braçalets (Story of a Girl and Twenty Bracelets, originally 1934). The edition of Forty Lost Years reviewed here contains Guillamon’s fascinating biographical Epilogue (photos included), which explains Arquimbau’s feminism and Republicanism in 1930s Catalonia. She was a political activist, campaigning for women’s rights and the vote during the Republic. A member of Esquerra Republicana, she became President of the “Front Únic Femení Esquerrista” (United Front of Left-wing Women).

Twice Forgotten

She went into exile after Franco’s victory in 1939, but like her fictional Laura Vidal, could not get to Mexico. Back in Barcelona a few years later, she was unable to return to her job as a civil servant because, according to police files, she was a “Marxist” and “has the worst possible morals”. Neither was true. The former means she was left-wing; the latter, that she had a sex life without being married. And, to her credit, Arquimbau refused to be discreet. She wrote that women should be free to have sex when and with whom they wished. Guillamon believes that her work can be favourably compared with well-known fiction-writing journalists of today such as Quim Monzó or Empar Moliner. That she was forgotten twice - under Franco and then after Forty Lost Years - was not due to a lack of quality. “What they never forgave her for was her absolute freedom.”

In Franco times, though marginalised, Arquimbau continued to write. She could not, of course, publish her caustic, radical articles. She won a prize in 1957 for the play L’inconvenient de dir-se Martines (The Unsuitability of being called Martines), but had no other success. Forty Lost Years slid away, largely unnoticed. But what a novel! It is “The feminist revolutionary classic I’ve been waiting to read”, as the author Preti Taneja, put it.