I couldn’t bear to leave

Rupert Thomson is enamoured of a dream Barcelona, a city of stunning views and intimate corners, great beaches, wonderful bars. The good life - everything in fact that the city’s authorities promote and puff

Thomson is seduced by the city that Joan Maragall called “the great enchantress”. Right from Amy’s long eulogy on the opening page, to Vic’s “amazing” view from his penthouse at the end, the book is full of detailed descriptions of the city. Here’s part of Amy’s riff:

…I couldn’t bear to leave. The quality of the light first thing in the morning, so bright and clear that the buildings seemed to have black edges…. The green parrots that flashed from one palm tree to another. Long walks in the Collserola in April to gather wild asparagus… It was a city whose pleasures were simple and constant.

What lifts the book out of being a sentimental paean of praise to the dream city (“quality of light!?” – many days from Guinardó you can’t see the sea-shore for the pollution) is that seduction does not blind Thomson. He takes his readers out of the tourist areas (I would wager this is the first ever foreign work of fiction set in Barcelona that does not mention Gaudí) and out of Barcelona altogether to Castelldefels and Santa Coloma. And the stories delve under the golden surface: they also feature rent-boys, gangsters, prostitution, violence against women, racism and porn films. Dreams can be nightmares. Amy would soon find that the city’s pleasures were neither simple nor constant.

Unstable Grasp on Reality

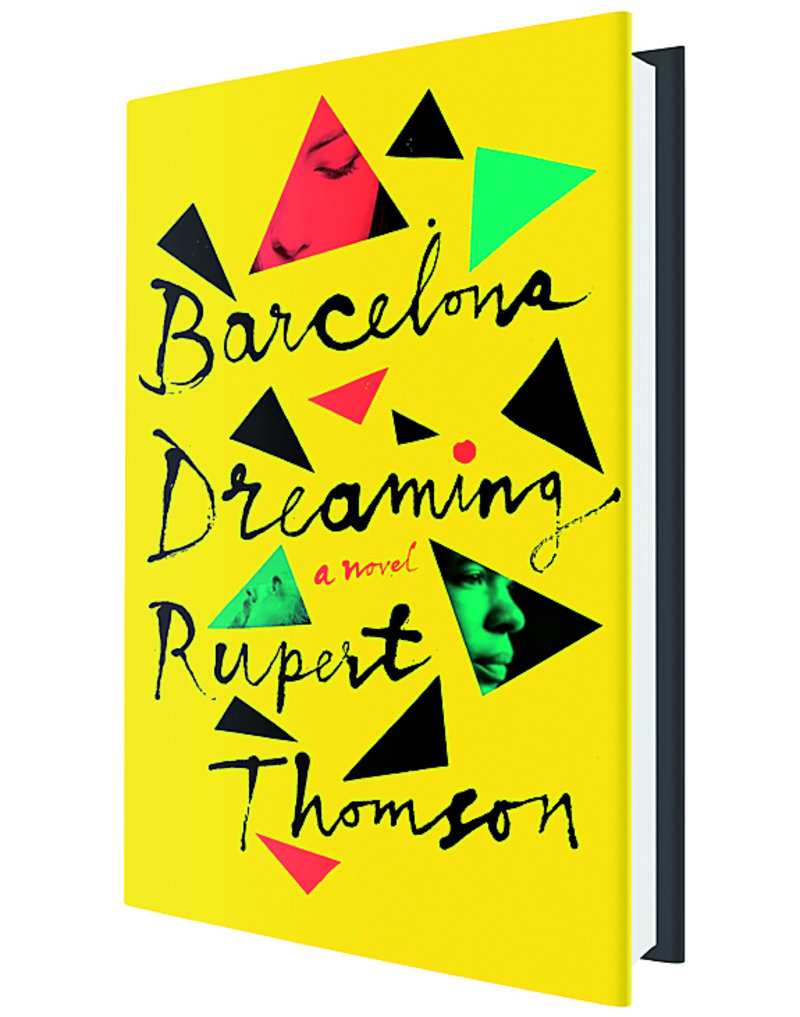

Barcelona Dreaming consists of three connected novellas, each 70-80 pages long and narrated by different protagonists. All three hold up very well. You want them to be longer, for Thomson tells good, fast-moving stories. His unsettled characters long for a better life, they caress it with their finger-tips, but it always slips away, just out of reach. Their dreams may be necessary for their sanity, but, unattainable, drive them mad.

In the first story, The Giant of Sarrià, Amy, a middle-aged Englishwoman separated from the Catalan father of her daughter, narrates her relationship with Abdel, a paperless Moroccan migrant, whom she hears crying one summer night in the car-park of her block of flats. Her kindness to him leads to a romantic and sexual relationship that shocks her daughter (do we ever conceive of our mothers as sexual beings?). The story is based in the narrow, tree-lined streets of wealthy Sarrià, but includes a part of Santa Coloma beyond the end of the metro where Abdel and his family survive precariously among rubbish and rubble. This is the best of the stories, especially for its surprising and pleasurable final twist.

The second The King of Castelldefels is the cleverest story, for the great skill with which its at first likeable narrator, Nacho, the self-styled ’King’ with a beautiful girl-friend and adoring stepson, is slowly revealed as an unreliable fantasist. Convinced of his own good nature, though in fact a violent alcoholic and serial philanderer, he inhabits the edges of a seedy world of pimps and night clubs.

The third story The Carpenter of Montjuïc has a supernatural touch. A mysterious carpenter found at a hidden-away address (Barcelona is a city of secret alleys) uses special wood to carve a chest of drawers that moves on its own. Or maybe it’s just that its central character Vic consumes so much cocaine that he imagines the chest in motion, along with a giant red-eyed boar charging across his ninth-floor terrace. Here, too, Thomson is masterly in expressing in few pages the contrasts between the narrator Jordi, a tranquil translator loving only his books and an unattainable woman-friend, and Vic’s excesses, unstable grasp on reality and sense of menace.

The Melancholy Star

The three tales are connected by some of the characters popping up in the other stories. For instance, Vic of the third story is a drinking buddy of Nacho in the second; or Montse, Jordi’s publisher in the third story, is Amy’s friend and Nacho’s ex-wife. These connections that seek to join up the novellas are a little forced. The real links binding the stories into one coherent book are Barcelona itself and its Brazilian football star from 2003-2008, Ronaldinho. These were the years of the city’s greatest prosperity. Tourism was soaring; business was thriving; and Ronaldinho was transforming Barcelona Football Club into a multiple winner of cups and leagues whilst playing with bewitching style. Barcelona Dreaming oozes nostalgia for this recent past just before the economic crash and Spain’s campaign to deny Catalonia an improved statute of autonomy, let alone a vote on independence. And like most nostalgia, this is false: peace and prosperity were only ever for the dominant class.

Ronaldinho pervades all three stories, but features most centrally as the King of Castelldefels’ friend, though it is the footballer with his charisma and god-given talent who is really the king. Thomson catches the toothy grin, the glamour, the good humour of the star and his underlying melancholy. At 25, reflects Nacho, Ronaldinho had reached the peak of skill and acclaim: what in the rest of his life can match such intensity?

Barcelona Dreaming is a very enjoyable book. Thomson writes elegant sentences extolling the city, with an undertow of melancholy that the longed-for, dreamed-of life is never so wonderful in reality.

book review

Versatile and Restless

I had not heard of Rupert Thomson before reading a review of Barcelona Dreaming and being captivated by the title. My ignorance was my loss, I think. Thomson is the author of 12 novels often admired by critics, though not bringing him big sales or fame. He is seen as highly versatile, changing settings, styles and themes with each book, which is perhaps why he is not better known.

Born in 1955 in Eastbourne, Sussex, Thomson had numerous jobs - advertising, English teacher, Bird’s Eye factory worker, bookseller - before getting his first novel, Dreams of Leaving, published in 1987. A restless character, changing places as much as the themes of his books, he has lived all over the wealthy parts of the world: Athens, Rome, Berlin, Tokyo, New York, Sydney, Hollywood (being paid to adapt a book for a film that was never produced) and, from 2004 to 2010, Barcelona.

The novels Divided Kingdom (2005) and Death of a Murderer (2007) were published during productive years in Sarrià, where he also wrote a memoir, This Party’s Got to Stop (2010) and the first draft of Barcelona Dreaming.

The film of The Book of Revelation (2006) brought him income. Katherine Carlyle (2015), a story of the frozen feelings of a woman born by IVF (in-vitro fertilisation) after the embryo was frozen for eight years, brought him further critical acclaim and controversy. Rupert Thomson says of his writing process: “There is always risk, exhilaration, mystery, and panic. There is also, hopefully, the discovery of something that feels both recognisable and new.” The city seen in Barcelona Dreaming is just that: familiar, but seen aslant, made new.