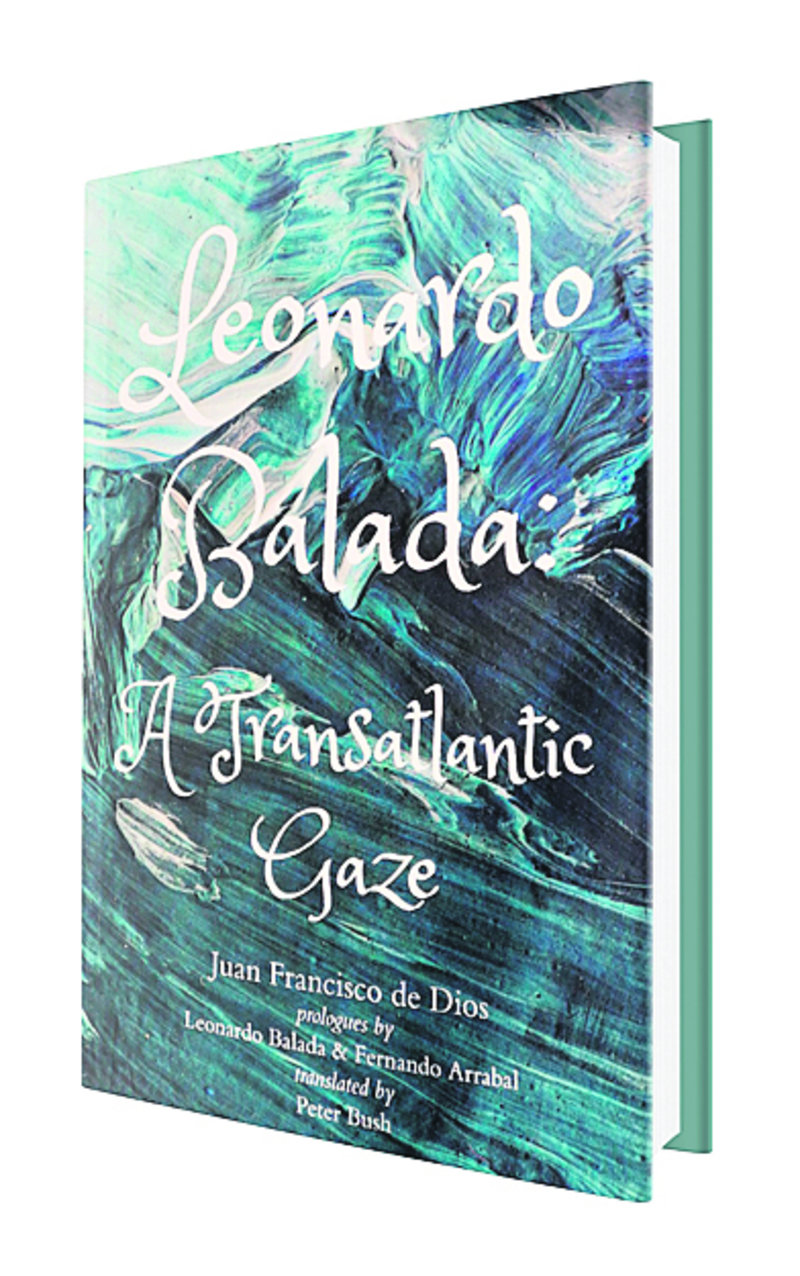

Avant-garde romantic

This biography of the composer Leonardo Balada is a strange and rather moving book. Balada’s life – even his name – was shaped by the Franco dictatorship, but then he soared above it to find freedom in both life and art

At the start of Chapter 11, the author compares composing music and making a suit. Both require a sense of proportion and the ability to create beauty. Both final products go on display in the public arena and are subject to criticism. Then a crucial difference is expressed. Unlike a suit, Balada’s music was a “flight from any preestablished system”. He had learned from his father, an anarchist tailor: “aspire to be different.”

Grotesque foolishness

Juan Francisco de Dios explains that Balada’s oeuvre can be divided into three main stages. In the early period, from 1956-65, Balada was “searching for his artistic identity”. The music is modernist and neo-classic, with conventional harmonies and developments. Though 12-tone music was then all the rage, Balada did not like it. He was studying at the Juilliard School in New York: “I wondered: How can they waste all the new techniques on such grotesque foolishness?” Balada determined to use these techniques to compose with “rhythm, movement to something of a climax, a kind of avant-garde romanticism.” His rejection, his biographer suggests, of a closed system of music was in part a political reaction. Balada had come to New York for freedom, to escape the confines of the dictatorship.

Then, from about 1966 to 1975, Balada expunged melodies to write “geometric” music. He concentrated on “lines and textures” instead of melody. Rhythm, however, was always present: he was never an abstract composer, unlike the abstract expressionist painting he saw around him and admired. One of his first works in this period was his Guernica symphonic movement (1966), inspired by Picasso’s painting. An anti-Vietnam War demonstration had recalled to mind his childhood memories of the Spanish Civil War. A constant throughout Balada’s life was this political commitment to the values of his parents. That said, he also worked with a number of unsavoury characters, such as the Francoists Cela and Dalí. Marina Sabina, his 1969 collaboration with Camilo José Cela, was the key work of this second period. The cantata tells the story of a Mexican shaman, popular among the hippies of the time for her use of hallucinogenic mushrooms. Her village demands she be hanged as a witch. It shared the fate of many great works by being booed at its 1970 Madrid premiere, though it had triumphed shortly before in New York. Probably, Balada (who was conducting) thought, this was because the Spanish audience, unlike the Americans, understood the words of Cela’s ferocious text.

Transatlantic unorthodoxy

His third period dates from 1975. Maintaining the pulse and geometric ideas of his second phase, he reintroduced melody. This means that his work is more accessible than that of many avant-garde composers. He tells stories and uses phrasing from Catalan folk-tunes. Among over 110 catalogued works, his longest is the two-hour opera Christopher Columbus, which premiered in Barcelona’s Liceu in 1989 with Josep Carreras and Montserrat Caballé.

The people he has known and worked with are a roster of late twentieth-century art: Picasso, Segovia, Alicia Alonso, Victòria dels Àngels, Aaron Copland, Rostropovich, among others. He was close friends with the exiled poster artist Carles Fontserè. On a visit to London he sought out the maestro Robert Gerhard. At a surrealist happening, Salvador Dalí hurled hard objects at paintings positioned round the stage, while several small groups improvised on Balada’s musical phrases. The book gives the impression of a buzzing Balada, full of energy: he was a social being, attending lectures, parties and art shows; he was politically engaged; he wrote articles; he composed several works at once.

The biography’s style is curious, modelled perhaps on the unorthodox rhythms of Balada’s music. The prose is precise and dense, but with vivid imagery, baroque flourishes and unusual word order. Here are two examples.

“This happened one morning when an elegant, eloquent gentleman with a fat wallet walked into the brand-new Balada tailor’s establishment.” (p.55)

or

“The prospect of leaving Spain in the early fifties, when the country was stuck in an economic situation worse than under the Republic, was as unlikely as fishing tuna out of a river.” (p.56)

Juan Francisco de Dios’ complex style forces readers to concentrate. I admire how he strives to describe and reflect music in words – a fearful challenge.

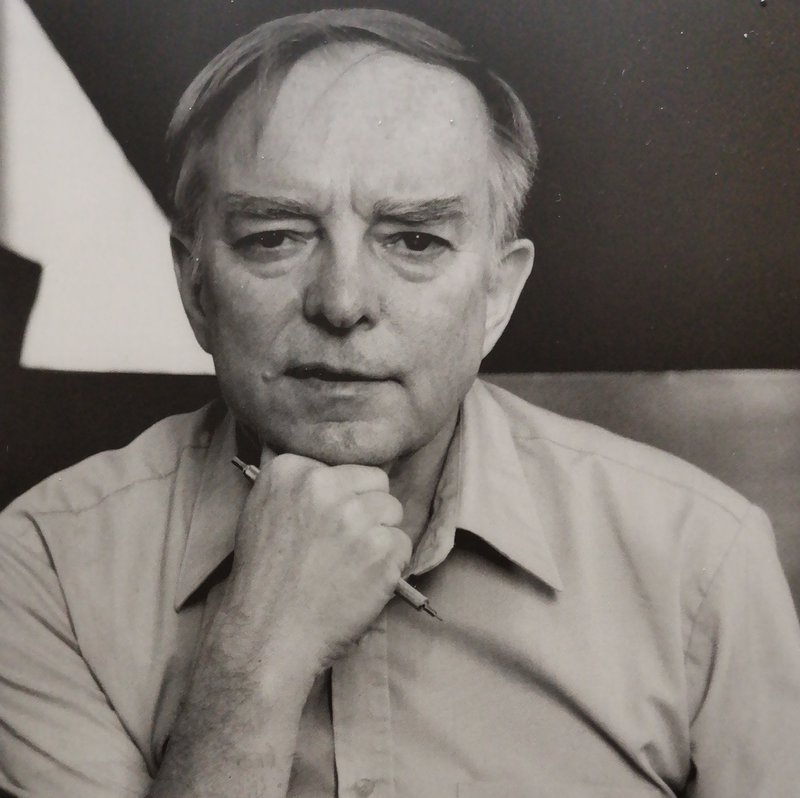

The arc of Balada’s life is movingly captured by the biography. A child of defeated, anarchist Catalonia, he lived with little money or employment in New York before becoming famous as a composer. The book romantically but aptly describes him as “an American from Barcelona with a transatlantic heart and an Iberian soul” (p.284).

book review

From plant to lion

Leonardo Balada’s parents were free-thinkers, avid readers and utopian anarchists. His father Pepito, a music-lover who took Nardo with him to concerts and operas, was a tailor with a shop on Barcelona’s Ronda de la Universitat.

Born in 1933, Balada grew up in Sant Just Desvern, a small town on the outskirts of Barcelona. Some of his earliest memories were of rushing with his mother Llúcia to take refuge from Civil War air-raids. His parents were vegetarians and atheists, married only in a civil ceremony. Balada was not baptised. After the 1939 defeat, he had the good fortune, through his parents’ contacts and in this slightly out-of-the-way town, to attend a girls’ school that was more liberal than the strictly national-catholic boys’ school. The photos show him, the only boy in the class. His given name was Nardo (meaning spikenard), but on military service he was told such an un-Christian name was not permissible and he became Leonardo. From perfumed plant to lion, Balada ironised.

He wanted to be a musician not a tailor and his parents, despite disappointment, did not impede him. In 1956 he won a music scholarship to New York. He hated the lonely city at first, but found friendship and support from many of the Catalans and Spaniards there and was energised by its dynamic culture. He did not abandon Catalonia or his family, though, returning most summers.

He became a prolific composer of concertos for violin, guitar and piano, symphonies and operas. In 1970 he gained financial security with a post teaching music at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh. He was later given tenure and remained there till retirement. He and his second wife Joan still live in Pittsburgh, to which he devoted his “Steel Symphony” (1972), 20 minutes joyously recreating, with 48 pieces of percussion, dustbin lids and a siren, the industrial noises of the city’s steel foundries (worth listening to: it’s on YouTube).

Juan Francisco de Dios’ biography ends with one of Balada’s late works, the choral La Pasionaria (2011), which puts to music the Communist leader’s 1938 farewell speech to the International Brigades in Barcelona. From his Pittsburgh old age, Balada returned in his creativity to the Catalonia of the start of his life.