Digital classrooms

Companies in the Catalan Edutech sector believe that the first year of the pandemic is a transitional one and that schools will be able to reflect on which tools add more value next year

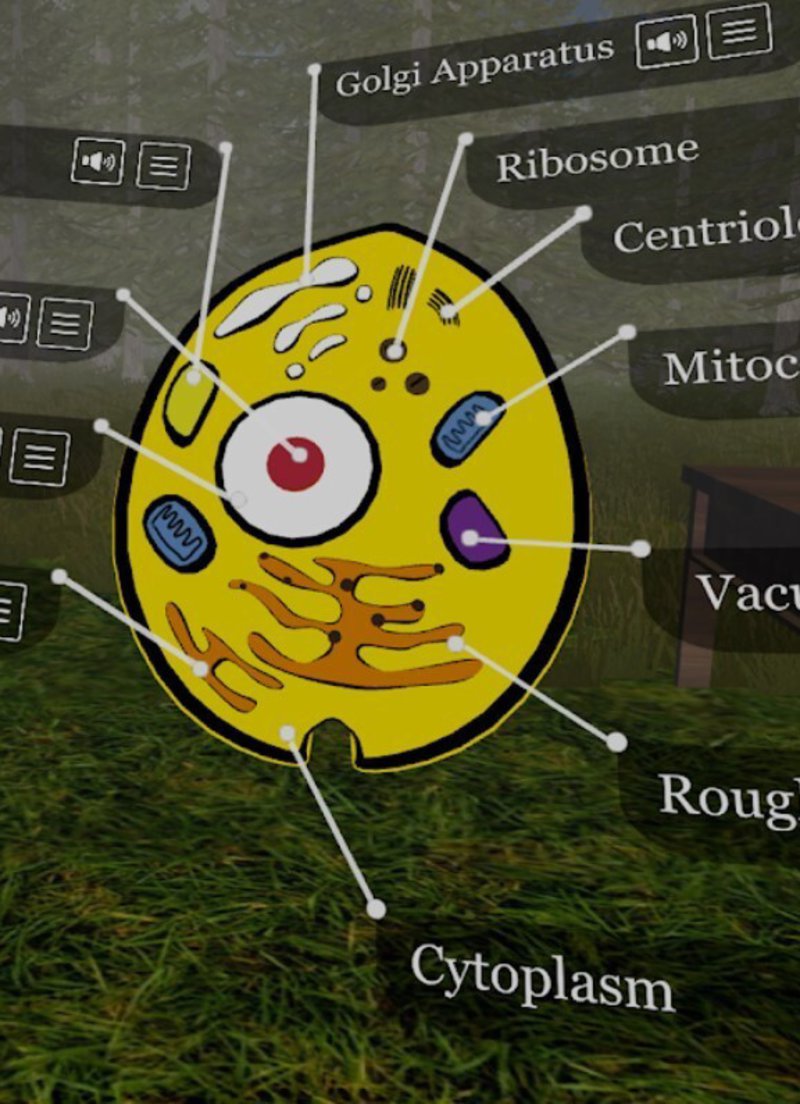

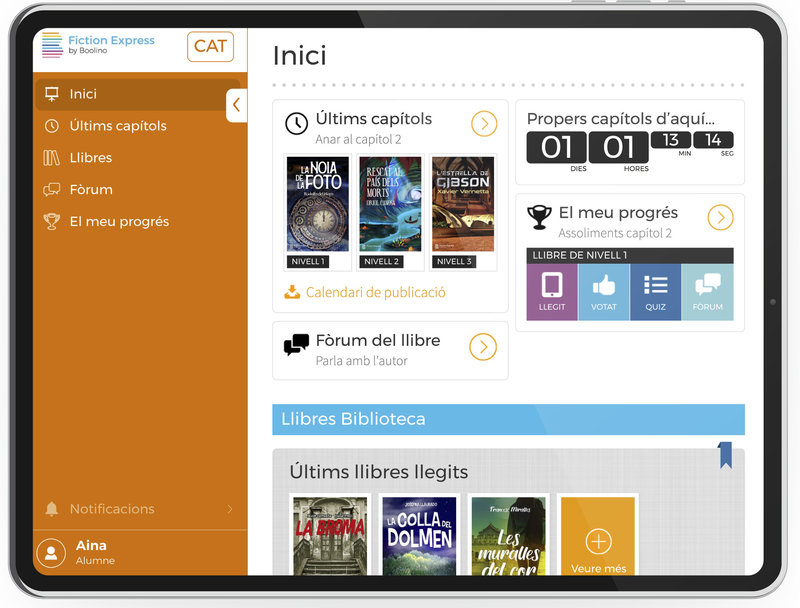

Participating in the creative process of the novel, talking to the writer and debating the best way to continue the story: these are the educational objectives proposed by Fiction Express, an innovative publishing house that wants to encourage reading and enhance reading skills among children and young people by taking advantage of the potential offered by the digital world. The platform allows students to read, interact, give opinions and make decisions, as the writer takes their ideas via a voting system and an online forum and incorporates them into the following chapters. Fiction Express is one of the 600 Catalan companies dedicated to the emerging sector of education technologies (Edutech). The pandemic has boosted business for some of these companies, while others have slowed down due to economic uncertainty. One thing is clear, however: nothing will ever be the same again, especially in terms of the relationship between schools and new technologies.

“Some schools are still in the 20th century, even after the pandemic, but there are others that have made a very important leap in recent months and are beginning to understand that digital platforms are not a complement, but rather, if they are well made and structured on the basis of the skill they are aiming to develop, can be a structural part of the subject,” reflects Cristina Puig, co-founder of Fiction Express. “All schools are now getting their act together, if they haven’t already, we’re all working in the 21st century now, there are no excuses,” she adds. Her partner at Fiction Express, Sven Huber, sees the glass half full: “I think we’re in the middle of the process, because there was a lot of improvisation when schools closed, and now, in September, although there’s been adaptation to technology, a lot has been done on the fly, in some cases taking the first resource they find, and if it’s free, so much the better.” It will be next year when we enter the third phase, he predicts, where “each school and teacher will be able to reflect on how technology can add value to the way we teach and learn, and make more informed decisions.”

Technology with value

Over 1,100 schools use the Fiction Express platform, available in Catalan, Spanish and English. For Huber, what is relevant is not that the tool is digital but that it “changes the relationship between students and the content they are learning, allowing it to be much more personalised, fun and based on project work,” far from the traditional – and obsolete – model of regurgitating memorised facts in an exam. The same idea of the importance not of technology but of how it is used and the pedagogy behind it is emphasised by Xavier Pascual, founder and CEO of BeChallenge, an online learning platform based on solving challenges. As he explains, it is contrary to the simple transition from paper to digital because that “doesn’t add value.”

This entrepreneur’s proposal is a tool that combines Design Thinking, challenge-based learning and cooperative work with the aim of “achieving meaningful learning that enhances soft skills: real life skills such as communication, creativity or teamwork.” To achieve this, the platform offers more than 38 challenges and the option to create them from scratch or reuse them by going to the library of the educational institution or the teaching community that comprises BeChallenge. One of the challenges that the company already faces is how to reduce waste, as it always strives to have a positive impact on the environment, be it for the school, the neighbourhood or the community. The BeChallenge method consists of seven phases, in which students go from discovering the challenge to solving it, performing different team activities along the way. The company has already helped solve more than 2,000 challenges, and although it initially focused on schools, in practice those who have requested its services most have been universities, vocational training centres and business schools.

Carlos Alonso is the president of the Edutech group. He believes that the pandemic has shown how companies in the sector are well-prepared and that they have done a good job contributing their experience and resources, even for free, during the months of lockdown. The problem is that, “in general, schools lack short, medium and long-term plans.” “It’s normal,” he admits, “that schools improvised at first, but now is the time to stop and think about what they need, analyse what is on offer and define transformation plans that include, among other things, teacher training programmes and gradual access to technology.” Based in Barcelona, the group wants to serve as the meeting point for all of the actors concerned, which is why it acts as an umbrella for 70 different companies and educational institutions. The Catalan company Glifing is one of those and shows that, if used well, new technologies allow each child to go at their own pace through the right personalised attention. Psychologist Montserrat Garcia is the creator of the Glifing reading training method, which improves both reading speed and reading comprehension through computer games. Garcia began designing this tool to help her dyslexic son, and although it was initially aimed at children like him, she soon realised it was a tool that could be applied to the whole class. “It can be adjusted upwards and downwards, so if a child is above average, it will also help them to move forward quickly,” says Garcia, who notes that while 10% of children have difficulty learning to read, up to “30% of children do not have problems but need specific help, because if they do not receive it, it will take them longer to learn and will be harder for them.” Around 250 schools currently use the Glifing method. “We have had more demand, especially from schools that already knew us, who had been thinking about it and then just decided to go for it,” says Garcia, “but not as much as we thought; this is a year of transition due to the economic uncertainty generated by the pandemic.”

feature education