Zdgt and Bst

Open a Quim Monzó book and odds are you laugh out loud. He is sarcastic and outrageous. He examines with X-ray precision his characters, who spin in a maelstrom of emotions and instincts, disconnected and disoriented

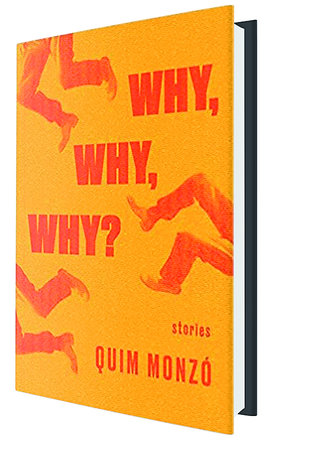

This volume of stories by Monzó was first published in 1992. Now skilfully translated to English by Peter Bush, it follows two other volumes of Monzó stories and a novel (Gasoline) from Open Letter, a non-profit publisher based in Rochester, New York.

Kissing the toad

Why, Why, Why? contains five fairy stories, where no-one lives happily ever after, and three stories about writing. The rest are the kind of story more normally associated with Monzó: of sex and folly in the modern city. “Black humour”... “biting satire”... “darkly strange”, are the usual kinds of comment about Monzó’s work. I have little to add. I will try to give an idea of his stories by explaining some.

One of the three writings about writing is the borgesian Divine Providence. A man spends 50 years writing in longhand 72 volumes of a Great Work. Then the ink starts to fade in the first volumes. As fast as he rewrites the disappearing pages, he still has no time to complete the book’s crowning conclusion. He has wasted his life. He hates himself.

Another is The Story, in which the writer writes an absolutely perfect story. Every writer’s dream! But he can’t think of a title. What can he do? He thinks and thinks. Then he tears up the story.

The five fairy tales lead to realistically disastrous endings. My favourite, The Monarchy, explains what happens to Cinderella once she’s married. Love of course does not last, especially if she is unwilling to accept that a king always does exactly whatever he wants. Here I’ll include no spoiler: the tale’s end is devastating. In The Toad, the handsome and lonely prince finally finds the toad he’s been searching for all his life, kisses it and it turns into a most beautiful princess with golden tresses. But then what? They know they’re meant to spend their lives together, but have nothing to say to each other. They don’t know each other at all.

This is the tonic of all his stories. People are driven to strive, to look for love, for sex, to hunt perfection, but then what? No love story turns out right, not even the one about the most beautiful couple who have the most exquisite sex (it’s so boring).

Alone and empty

The stories of couples in conflict are the most characteristic of Monzó. In one, a blue man approaches a magenta man drinking in a café and tells magenta that he is magenta’s wife’s lover. He wants magenta’s advice. Blue asks a perfectly logical question, but the story turns on both husband and lover behaving quite differently from the normal. With detailed logic, Monzó turns conventional stories upside-down.

Apart from The Monarchy, my favourite here is Married Life, a novel in two pages that sums up Monzó’s bleakness and humour. I will relate this entirely, spoiler included. After eight years marriage Zdgt and Bst (Monzó loves ultraunpronounceable names) arrive at a hotel in a city where they’ve gone to sign some documents. (Monzó is extremely economical in extraneous subject-matter: what city or which documents is irrelevant.) They clamber into their room’s twin beds, read their books and hear a couple screwing (I started to write ’having sex’ but Monzó opts for the direct ’cardar’) in the neighbouring room. The couple smile, joke and turn out the lights to go to sleep. Zdgt feels aroused. He thinks of waking his wife, but she might say she was too tired for sex, so he doesn’t. He masturbates quietly. Then Bst comes over to his bed and starts caressing him. He says he doesn’t feel like it. Bst goes back to bed and he hears her in turn masturbating. The story climaxes in fierce climax:

He cries into his pillow, sinks his face in as far as he can. His tears are hot and plentiful. And when he hears Bst suppressing her final moan with the palm of her hand, he screams a scream that’s the scream she is holding back.

Monzó’s characters are left alone and empty, and the sex and worries about sex that fill their minds and impel their bodies are little compensation.

If you haven’t come across Quim Monzó before, buy this book and buy it in Catalan too. In 1994 this was one of the very first books I read in Catalan. It’s a great learning aid because the stories are so short (except for two of them) that you can look up every word you don’t know, then reread the story for meaning. And they are so good that you are driven to learn the language to understand them.

Monzó revels in the absurd details of everyday life. His characters’ conversations are lacerating and fast; their internal monologues include all the irrelevances that pop into the mind, often at the most serious moments. They seem both completely normal and seriously demented. With enormous skill he glides between the inconsequential and the profound.

And you laugh, hoping we aren’t really like that, but fearing we are.

book review

Surreal realist

In 2007, when Catalonia was the invited country at the Frankfurt Book Fair, Quim Monzó gave the inaugural address, which sums up his status as the outstanding contemporary fiction writer in Catalan. Characteristically iconoclastic, his address took the form of a story.

Monzó (Barcelona, 1952) is also one of Catalonia’s biggest-selling writers, both in Catalan (El perquè de tot plegat has sold 130,000 copies to date) and in translations to over 20 languages. He himself is a translator, of books from English to Catalan. And he co-wrote the dialogue for Jamón, Jamón, the Bigas Luna film that introduced us all to Cruz and Bardem.

In the 1970s he published reports from war-zones all over the world, from Ireland to Vietnam. His first volume of stories, Uf, va dir ell (Errgh, he said), dates from 1978. Since then, he has published eleven. These and his three novels have won numerous prizes. His fiction is playful like Robert Coover (whom he translated) or Cabrera Infante, paranoiac like Kafka and polished to cut ice like Julio Cortázar. All these are influences Monzó himself acknowledges. But who knows if he was serious when he named them? Monzó loves to confound critics and bamboozle readers.

He writes a daily column in La Vanguardia, articles collected in eleven volumes to date. In 2009/2010 an exhibition about him was held at the Santa Mònica Arts Centre on Barcelona’s Rambles. He wondered if he had died.

Monzó is a glorious original heir to a Catalan tradition of surrealism. At times his stories are like a Dalí picture, where extraordinary detail flowers into monstrous images. Spanish esperpento is in his ancestry, too. Think of the films of Berlanga who twisted reality up a notch to the grotesque.