Back to art

Six art professionals discuss the first works they want to rediscover when we leave lockdown behind

Tired of looking at the world through the small screen? Soon we will be able to go back to museums and see live art again, interact with it without filters, become intimate with it, recognise it and recognise ourselves in it. Six art professionals tell us about the works they cannot wait to reconnect with.

Mercè Alsina, art critic and independent curator

Desaparèixer de si, 2020, by Ares Molins i Masat, Guillem Rodri and Carlos Pina with Rita Batet. Sant Corneli Chapel, Tomàs Balvey Archive Museum in Cardedeu.

“I will go to see Desaparèixer de si, a project that was suspended just a few hours after its inauguration. It’s an exhibition by Ares Molins, Guillem Rodri and Carlos Pina with Rita Batet that I curated with Enric Maurí for the cycle Santcorneliarts (2). Why? To face the concept of running away from oneself from the perspective of exploring that otherness that inhabits us, in the context of an exhibition that has been stolen from view and only exists as traces. Through the text of the same title by David Le Breton, the exhibition uses art to reflect on contemporary society and how individuals sometimes feel excluded and immersed in an inner exile, entrenched in social life; and we claim our right to abstain. The exhibition proposes a reflective transitoriness, to think about reality and reestablish links with what’s inside us. Perhaps after Covid-19 this will be an urgently needed exhibition. The works were conceived specifically for this project based on joint work.”

Vicenç Furió, art historian

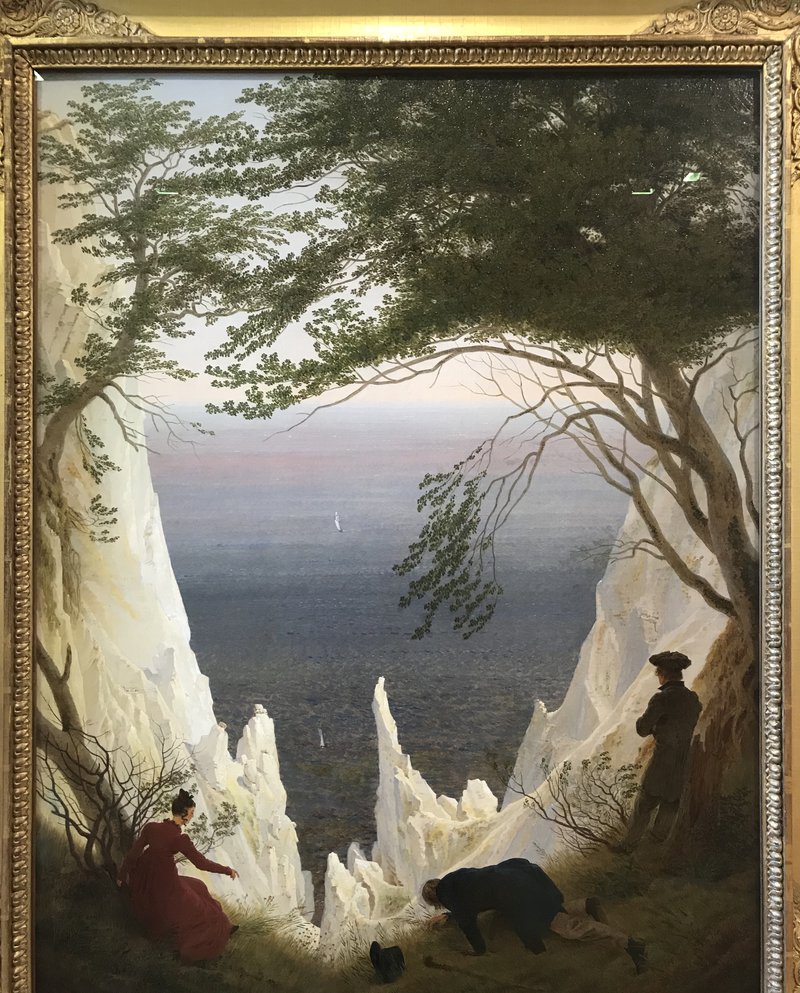

Els Penya-segats blancs a Rugen, 1818, by Caspar David Friedrich. Oskar Reinhart Foundation, Winterthur.

“During these difficult times, I choose a work that expands my spirit: Els Penya-segats blancs a Rugen, by Caspar David Friedrich. It’s a magnetic painting, which has been linked to the artist’s honeymoon and has some religious and even political symbolism. But what amazes me about it is its original composition, the spatial sequencing and the grading of planes that lead the eye to the depths of the landscape, the sea and the sky. I like the fantastic white limestone rocks, the contrast of colours, so vivid and at the same time so nuanced. I see the branches and feel the breeze. The work makes you imagine the thoughts of the figure on the right, which inevitably mix with your own thoughts seeing the full image, the one you see as a spectator. I’m drawn to the window, the corridor that leads the image towards the infinite.”

Teresa Grandas, Macba curator

Èxtasis de la beata Ludovica Albertoni, 1675, by Bernini. Església de San Francesco a Ripa de Roma. Muro pintado por el artista con pincel del número 8, entre los días 10 y 19 de septiembre de 2006, by Isidoro Valcárcel Medina.

“There are a lot of works I would like to see when we can go out again, but in a moment of confusion like the one we’re going through, I’ll refer to just two. One is the sculpture of Ludovica Albertoni, by Bernini, in which the physical sensuality in the mystical ecstasy of the Beatus diffuses the boundaries between faith and eroticism, even more intensely than in The Ecstasy of St. Teresa (1652). To me it appears transgressive, because of the confusion between seemingly separate notions and the role of power in defining them, being the driving force behind Dokoupil’s photographic essay Madonnas in Ecstasy (1987). The other work is the painting Muro pintado por el artista con pincel del número 8, entre los días 10 y 19 de septiembre de 2006, by Isidoro Valcárcel Medina. I won’t be able to see this work, as it was designed to disappear shortly after it was made, erased by the thick brush of another painter. From the ambiguity and subversion of established notions, the artist reflects on the meaning and fleeting nature of things. In very different ways, the two works place us in a position of doubt and reflection, both necessary today.”

Malén Gual, Picasso Museum curator

Interior, Strandgade 30, 1908, by Vilhelm Hammershøi. Aros Aarhus Kunstmuseum.

“In this time of confinement and loneliness, the works of the Danish painter Vilhelm Hammershøi are an invitation for contemplation, peace and recollection. Hammershøi, whose work has been forgotten over the last century and has been revalued with recent exhibitions, worked in his hometown of Copenhagen and is best known for his interior portraits. Using a limited palette, his handling of light achieves an intimate and melancholy atmosphere, out of time, both cold and elegant at the same time. The female characters, his sister Anna and wife Ida, portrayed from behind, look out through a window and half-open doors, but without attempting to leave the room that protects them. Are they afraid? Are they waiting for someone? Isn’t this tense attitude of waiting, of uncertainty, what we are feeling right now?”

Alexandra Laudo, independent curator

Double Excalibur, 2020, by Pere Llobera. La Capella, Barcelona.

“A few days before the state of alarm began, we inaugurated Pere Llobera’s exhibition Faula rodona. Sols i embogits; entre la precisió total i una cançó de Sau in La Capella. It’s a long and strange title that, bearing in mind what happened next, seems premonitory to me in many ways, as was the spirit underlying the exhibition. At the behest of I. Kertész, Llobera aimed to invoke conflict and wonder and speak of “the metaphysically abandoned world.” These days, I envisage all the empty museums, all the closed exhibition halls and all the unseen works on display, and I find it a disturbing and beautiful image, which could well be a reflection of this meaningless world. But at the same time I think no, this human-free existence has autonomy, a meaning that us alien to us, and, as Kertész says, it is perhaps humanity that has been metaphysically abandoned. The first exhibition I want to see again is Llobera’s, to remember how that evening we saw each others’ smiles and greeted each other with hugs and kisses; to contemplate the dual mirage of the Excalibur sword emerging from the depths of the murky waters and to think that wonder still exists, we only have to invoke it.”

Pilar Parcerisas, art critic and independent curator

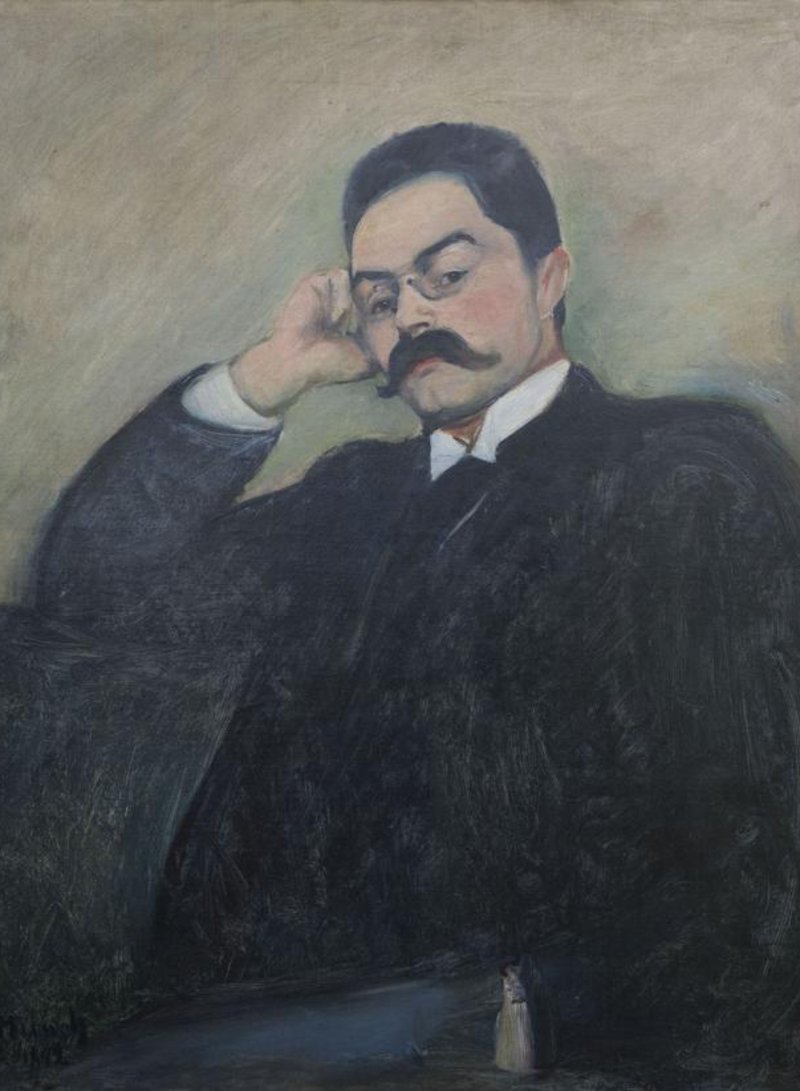

Portrait of Thor Lütken, 1892, by Edvard Munch. MNAC.

“I’m fascinated by this portrait of Thor Lütken, Edvard Munch’s lawyer, painted a year before The Scream (1893). By a quirk of diplomatic history, it ended up here in Barcelona, temporarily transferred to Amics del MNAC. For a year I’ve had a press clipping on my desk about this painting, which often goes unnoticed in the middle of portraits of the wealthy bourgeoisie. This Munch is more than a portrait of commitment. I’m attracted to the realism of the face, which projects a distant, serene and defiant look at the onlooker, with a Nietzsche-style moustache; the arm holding the head in a pensive position, which contrasts with the rocky, leafy landscape of Norwegian fjord blues at night, huddled under his jacket, with a couple embracing by a lake. This painting is no stranger to the love, sex, death, tragedy and madness that undermined Munch’s life.”

art