Hanging around in train stations

There is a long tradition of English-language travellers fascinated by the back-roads of Spain who write a book of personal impressions, conversations with local people, history and literature. Brett Hetherington joins a list that includes George Borrow, Laurie Lee, Gerald Brenan, Rose Macaulay and Penelope Chetwode

There is a long tradition of English-language travellers fascinated by the back-roads of Spain who write a book of personal impressions, conversations with local people, history and literature. Brett Hetherington joins a list that includes George Borrow, Laurie Lee, Gerald Brenan, Rose Macaulay and Penelope Chetwode.

On his slow travels, Brett does not walk like Laurie Lee, nor ride a donkey like Penelope Chetwode, but takes trains and buses. From the smallish town in Catalonia where he lives, he winds his way on complicated train routes into Aragon. He is accompanied, in his mind, by two respected literary companions: Juan Goytisolo, self-exiled from Barcelona, an outsider if ever there was one, and Antonio Muñoz Molina, who gives him something of a destination: Úbeda.

After wandering across Spain on public transport, at the end he returns to Catalonia and to Muñoz Molina, whom he praises for his “tender reverence for so many ignored bits of the physical world, especially the comfort of little things in our domestic lives” (p.132).

Passive and active

First stop is Zaragoza, but before he reaches the big city, the meandering trains give him views of the sea, of vineyards then olive groves, of the Magic America Sex Shop, of young women in the “summer uniform of cut-off jeans”. The beach glimpsed makes him think of the conflict between Catalonia and the Spanish state, as some loud Spaniards had threatened to boycott Catalan holidays. He has to change trains. There is industrial action on the railways: in the waiting-room, the author asks a man why railway workers are taking action. This man complains about strikes and politicians, naming Jordi Pujol, which leads to four paragraphs on who Pujol is. The traveller, now on the station platform, talks to a Pakistani, Ahmed, who explains his job in a supermarket. At last, on a train again, he watches girls cluster round a mobile and an old man struggle alone with one. A grandmother looks after two children and he thinks how “Spain would virtually fall apart without the abuela”. And these elderly ladies are often the most ruthless about barging into queues with the magic, deceitful mantra… “just a tiny little question.”

I hope the above paragraph gives some idea of the book. These are Slow Travels. Brett’s good on the “little things”. He starts from the details of a scene, what he sees, to then generalise to what he thinks. He is passive, drawn along by what trains or buses are available, with no fixed schedule. And he is active: he boldly accosts people, so he addresses the man in the waiting-room and approaches Ahmed. His style when he talks to people is both calm and provocative. When he tackles a poor shop assistant in Zaragoza on why she sells ineffective lucky charms, the conversation leads to his asking her if she believes in God. She reddens in embarrassment. He tells her not to worry and that he is leaving.

It is an off-the-beaten-track travel book, not a guide book. There are no recommended hotels, bull-fights, mantillas, palaces or golden sands. His strengths lie in sketches of contemporary Spanish life and the people he meets: the “bits of the physical world” he admires in Muñoz Molina. In Zaragoza, after a Goya exhibition, he drinks with Maggie who is reading Trainspotting in an English-themed pub. He respects her because she is getting involved in Spanish life, unlike so many foreigners. At yet another railway station he approaches a Senegalese student of the Koran. Brett likes him too, for uninhibitedly and unusually reading in a public place. Brett’s always waiting around at stations as it is August and trains are full. It is very hot, but Brett from the dry heart of Australia likes the heat.

Going slow

On the train to Extremadura he reads Goytisolo and looks at the scenery and other passengers. Boring? No, because this is what everyone does on train journeys. Often, in his precise descriptions of these brief encounters and fleeting events, he uses quite long sentences, with unusual structures. With a preposition he sometimes starts a sentence, adding dependent clauses, so you have to go back and read again to see how the sentence works. All this skilfully forces readers to slow down and be less likely to commit that too-common sin of reading too fast. Or not always so skilfully: at times the curious syntax drifts into loss of meaning.

In Mérida he meets again a whole number of people. He reports a conversation about Catalonia with a barman. In the street he chats to a gypsy flamenco singer. He talks to a man collecting junk from rubbish containers to sell. He visits an English couple, living cheaply by a lake in the beautiful countryside. All these are affected by the 2008 crisis that most people have not recovered from. Yet they see themselves, Brett posits, not as victims, but as entrepreneurs.

Andalusia to Catalonia

Brett visits Córdoba, Écija, Jaén, Málaga and Úbeda, all in Andalusia. He ends with a final chapter on Catalonia as he approaches home. He is forced to take an AVE for a second time. Slow trains, where they still exist, are notoriously underfunded.

This is a short book, long on content. He moves slowly, but the book moves rapidly through scenes and themes. At times, though, these shifts are too brusque. One example: Brett mentions the “subtle, engaging memoir titled An Unknown Woman” by Lucia Graves, but then says nothing more about her except her throwaway comment that well-off Spaniards in the Franco years used to order books “by the metre” merely as decoration (p.140). Lucia Graves is used by the author to make a point, but she and her memoir are not integrated into the flow of his book. Such over-brevity is frustrating for the reader and inelegant, too.

Brett’s curious style is disconcerting at times. Perhaps it should be so. He draws his readers through contemporary Spain. Not all, he shows, is wonderful. But toward the end, in otherwise rather dull Jaén, he stumbles on “squares full of people eating and talking in the open air… This was Spain at its absolute unaffected best: men, women and children of all ages socializing smoothly together in large groups.” The Mediterranean life! Despite crisis, despite poverty, despite the rise of fascism: doesn’t it take your breath away?

book review

Slow Travels in Unsung Spain

Author: Brett Hetherington

Pages: 150

Publisher: Apocryphile Press (2019)

www.bretthetherington.net

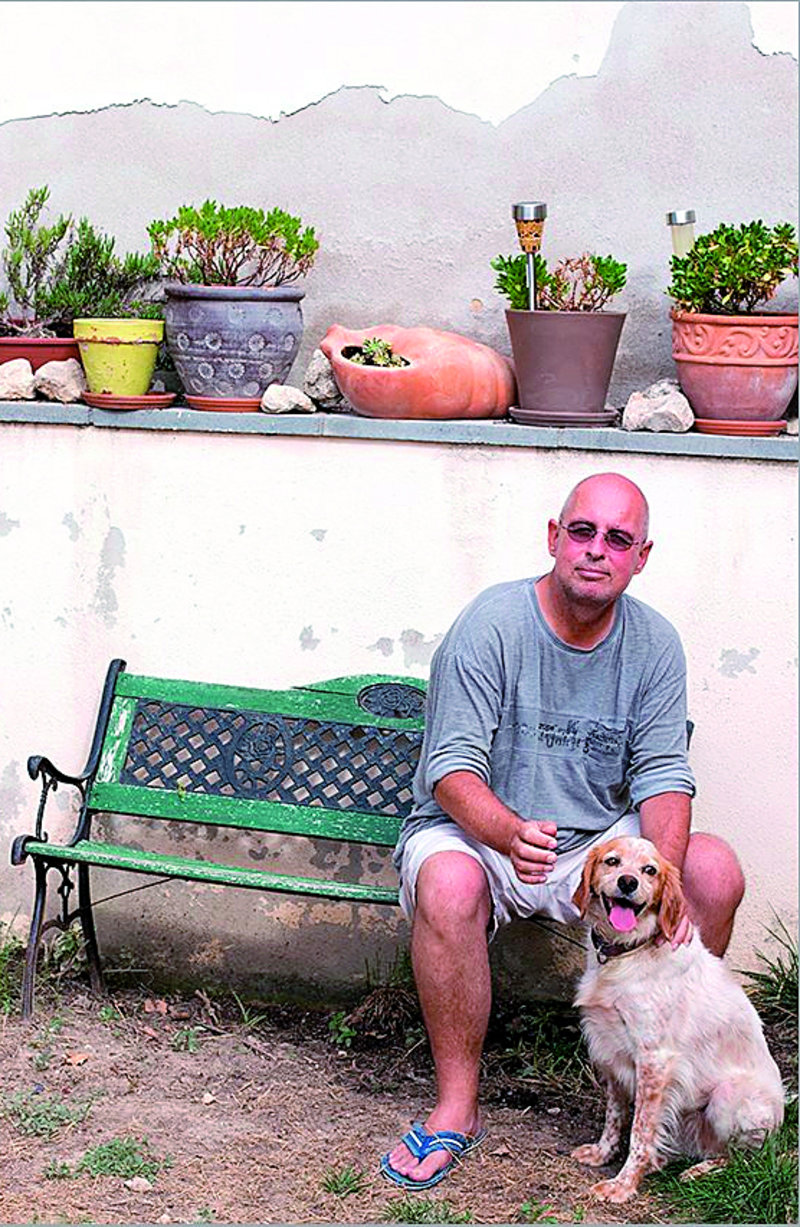

The Australian Parent

Brett Hetherington, born 1968, is a teacher and writer. Brought up in Australia’s inland capital Canberra and graduating in Political Science and History from university there, he has lived in a small town near Barcelona with his partner/wife Paula and their son Hugo since 2006. He has written for Catalonia Today since 2008, as well as various other magazines, both in Australia and Catalonia. He contributes regularly on Catalonia’s politics and culture to Australia’s ABC Radio.

Before Slow Travels, he published a book about parenting, education and gender titled “The Remade Parent: Why We Are Losing Our Children & How We Can Get Them Back” (2013). Brett looks at why men often fail as fathers and why women increasingly opt out of parenting. The ambitious book calls on parents to stop running so fast in their hectic recession-dogged lives and think how they can provide the “continuous care, concern and affection” that children need.