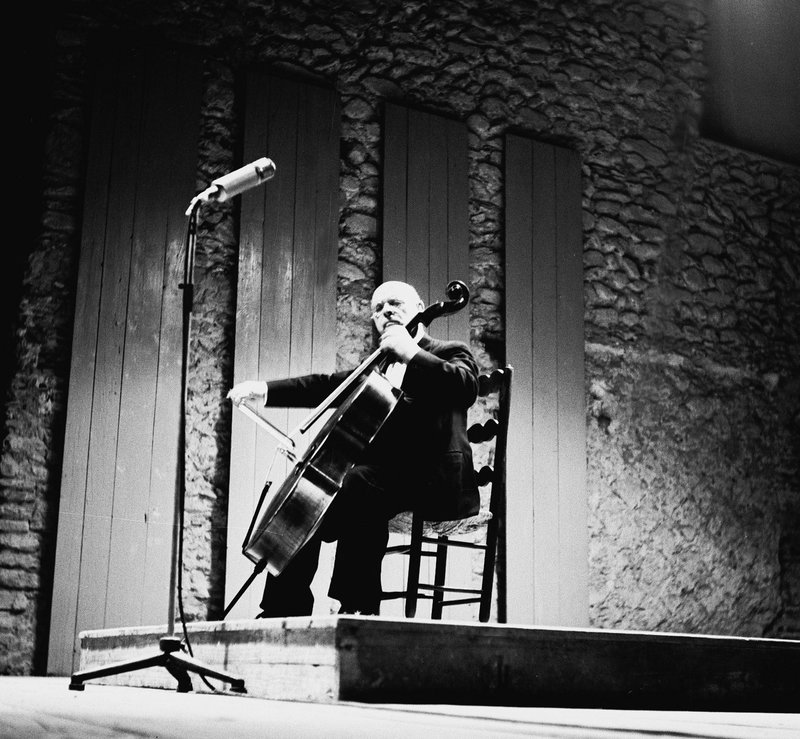

Remembering Pau Casals

The first Catalan name I ever (knowingly) heard was that of Pau Casals. I was around eight years old and listening to a Monty Python comedy record.

An English mock-commentator’s voice introduced “The Sonatino in E sharp by Antonio Vivaldi to be played by Pablo Casals during his 400 foot plunge into a bucket of boiling fat.” Next was the sound of a violin soloist playing a few bars, then a long scream followed by the sound you’d expect of someone falling through the air into a container of liquid.

This was very funny as a kid but, in fact, Casals was mainly a cello player and so much of this man’s life, his beliefs and practices, make Monty Python’s comedy sketches seem tame and dull in comparison.

Pau Casal’s mother Pilar (who was originally from Puerto Rico) had brought him up to treat everyone as an equal. He claims she openly breastfed his baby brother in front of the Spanish infanta (the sister of the king) on their first day at the royal palace in Madrid. The young cellist had gone there to audition for a scholarship from the queen but it turned out to be barely enough for the family of four to live on.

Fluent in seven languages, Casals became a public friend to many well-known figures in the arts, including Colonel George Picart, a hero of the infamous, anti-semitic Dreyfus case in Paris at the turn of the century.

Casals was full of contradictions, too. Adventurous by nature, he was also a creature of habit. He started more than 80 years of his life every day playing two preludes and fugues by Bach but somehow found new vitality in himself and the music every time he did so.

Rightly though, it is his musical genius that he is still remembered for.

His belief that intuition or instinct is the most important factor in the creation and performance of music was not then a popular opinion. He was also controversial in his development of radical methods of using his main instrument but understood the fundamental importance of “playing songs in the language of everyone.”

Listening to his interpretation of the old Catalan folk song (Casals says it is actually a Christmas carol) ‘El Cant del Ocells’, or Song of the Birds, brought tears flooding into my eyes and tugged at my heart strings in the first handful of notes he played. He seems to have the ability to drag you under the waves for a few wrenching seconds then within a few beats, thrust you up, blinking hard into the warmth of the sun.

My only criticism of this extraordinary man (who was also an accomplished orchestra conductor) is his mental and emotional blindspot towards the monarchy. Casals called himself a life-long Republican but his continually fawning attitude towards them was at odds with his stated attitude.

While he understandably felt indebted to the Spanish royals for early opportunities in his career, it seems to me that in his autobiography ‘Joys & Sorrows’ he exaggerated the “friendship” he had with King Alfonso XIII and Queen Maria Cristina who, as his supposed “second mother”, gave him decorative honours and jewels. Casals failed to state that their riches and position came at the expense of ordinary people such as his own family.

Just like his name Pau, Casals was essentially an international man of peace. Surely, this is partly because three major wars straddled his life, the same way he straddled the cello. He once said: “The love of one’s country is a splendid thing. But why should love stop at the border?” These are still important sentiments today, almost half a century after his death.