Way of the BULLY

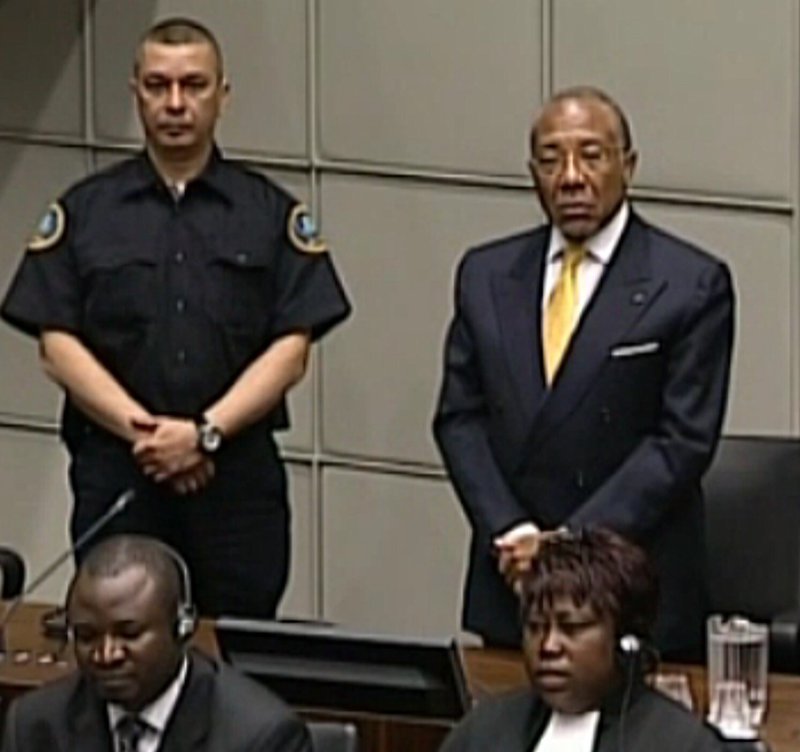

In 1997, Liberians chose a new president. A multinational peace force had just occupied the country to bring a murderous civil war to an end and hold an election. The main contenders were Charles Taylor, the bloodthirsty warlord who started the war, and Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, a prestigious economist with an impeccable humanitarian record. Taylor ran under an unusually candid slogan: “He killed my pa’, he killed my ma’, I’ll vote for him.” The UN-sponsored election was fair, and its outcome clear-cut: 75% for Taylor, less than 10% for Sirleaf – for many Liberians thought submitting to Taylor was the best way to ensure peace. Vain hope: just as the multinational force, baffled but relieved, pulled out while singing paeans to democracy, Taylor instituted a despotic kleptocracy and, soon enough, the example of his success led to other warlords resuming the civil war.

Such is the way of the bully: in the end, terrified victims are willing to exchange any long-term advantage for immediate peace – just as the battered wife repeatedly forgives her abusive husband because she fears him so much.

Half a millennium ago, Machiavelli advised the Prince to aim to be both loved and feared but, if forced to choose, always choose fear. He also cautioned, however, against taking away what people believed was theirs, for this would foster hatred towards the Prince, and people always strive to destroy those whom they hate. Machiavelli, however, did not fully realise that what people believe is “theirs” depends on each person’s self-image – and bullying can manipulate this subjective perception. Just as schoolyard bullies humiliate their victims and abusive husbands belittle their wives, the Spartans’ serfs were made to wear a cap resembling a dog’s head and New World slaves were brutally punished for staring at their masters. The goal is always to destroy the victims’ self-respect to make them more pliable.

Those who fail to understand the viciousness of Spanish repression against Catalan independentists forget what even schoolchildren know. Spanish prosecutors’ zeal not just to punish independentist leaders on trumped-up charges but also force them to recant and repent, or their tolerance of anti-Catalan abuse on social networks and mass media, coupled with their swift reaction when the abuse is hurled in the opposite direction, are all reminiscent of age-old bullying tactics. This goes a long way towards explaining why the most conciliatory moves by some Catalan independentist parties are so often met with both derision and heightened repression – most recently when J.M. Jové, an independentist member of the just-established “dialogue table” with the Spanish government, came out of the first meeting to find himself facing a court indictment for disobedience and an executive order to seize his personal assets as bail. Meanwhile, European observers praise the virtues of dialogue (just as in 1997 the UN preached respect for the Liberians’ democratic choice, or a battered wife’s neighbours praise the beauty of marital love) and try not to look too closely. When an approach works, it is only natural to keep using it: such is the way of the bully.

Yet human beings also eventually learn. In 2005, after another peace force ended their second civil war, Liberians voted again, and several warlords ran for office – but this time Ellen Johnson Sirleaf won the presidency. Perhaps many Catalan politicians, as well as many European observers, who seem to believe meekness and submission may be a way to end repression, will eventually learn that victims’ subservience, however disguised, rewards abuse and thus very rarely ends it. Sadly, bullies instinctively understand this only too well, and play it to their advantage.