Far from the 1918 pandemic

Comparisons between today’s health crisis and the one in 1918 are inevitable, but that catastrophe led to millions of deaths in the world

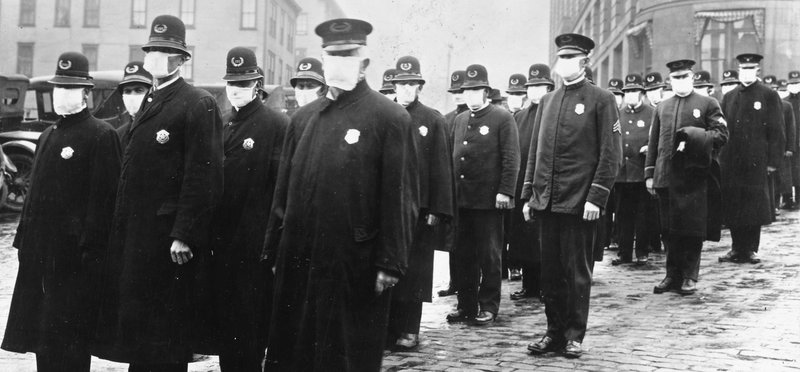

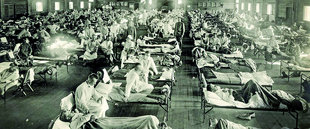

Some in the media have compared the current coronavirus pandemic with another health crisis that in 1918 caused between 40 and 100 million deaths around the world: Spanish flu. Yet, the comparison is somewhat false. The health situation in 1918 was nothing like today, and nor was the reaction of the authorities. While the Covid-19 pandemic has been treated with relative transparency and backed by a powerful health system, a century ago the authorities tried to cover up the crisis until the events overtook them. Nor can the medicinal arsenal we have today be compared with what they had then. They had no antibiotics, and while these medicines do not work against the virus, they fight the bacteria that take advantage of weakened immune systems. Often it is these bacteria that cause the fatality. No less important are hygiene conditions now compared with a century ago, and it is perhaps not an exaggeration to say at least half of the victims of Spanish flu might have survived had they had the hygiene standards we do today.

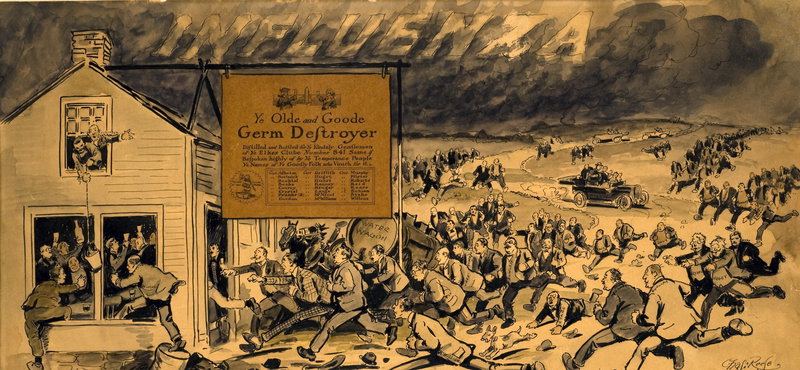

What impression do we get of that pandemic from the newspapers of the time? One very clear thing: the 1918 epidemic shook everyone up. Anxiety gave way to a feeling of impotence, and ultimately of failure. No one knew how to confront this flu that took so many lives.

In an interview in La Publicidad magazine, Ramon Turró , head of Barcelona’s municipal laboratory, explained the cause of the general feeling of anxiety: “We know little to nothing about the germ that causes the flu, nor the mechanisms that propagate it. We do not know what to do to avoid it or mitigate its spread.” And at the end of October, at a session of the Royal Academy of Medicine, he added: “We find ourselves in the same place regarding the plague.”

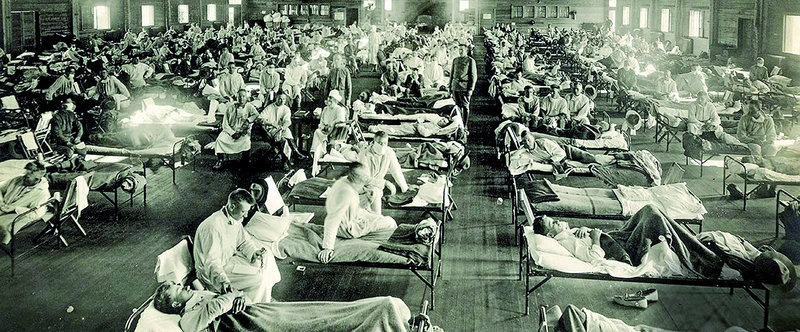

The 1918 health crisis exposed shortcomings in organisation, personnel, and material. Barcelona had always got through other epidemics, but this one overwhelmed the city. Yet, the same Turró, in an article in La Publicidad on October 15, talking about more advanced countries, also pointed out: “Their admirable health systems have not helped them, as ours has not helped us,” and he added that no one was able to defeat the disease “because right now against this devastating evil there is no defence.”

The press at the time revelled in controversies about the cause of the flu being Pfeiffer’s famous bacillus – they did not know that the cause was a virus –, about using anti-diphtheria serum as a prevention, about the lack of medicines, about the social impact of closed schools, about overwhelmed funeral services, about the tax put on some rents to help cover the extra expenditure.

If you can’t see it, it doesn’t exist

What was the attitude of the Barcelona press? The newspapers reported on the origin and cause of the flu, its symptoms and treatment, the development of the epidemic and the policies implemented by the authorities. Some newspapers, such as Las Noticias, every day printed the names, ages and addresses of those who died. As the list grew, it became clear that this was no normal flu.

Between the end of September and the beginning of October, some newspapers, such as La Vanguardia, Diario de Barcelona and La Veu de Catalunya, took a more restrained approach to reporting the development of the epidemic, relating the facts, without much commentary, although that alone was enough to cause general alarm.

The newspapers also reproduced the official bulletins that from the first day assured the public that the epidemic was on the downward curve and was largely benign. Some papers acted as if this was true. Las Noticias was one that spent October repeating the message that the epidemic was in decline, which meant it had to jump through hoops when fatalities spiked. In fact, its editor became a victim of the epidemic.

As for La Publicidad, it was very critical, but also sent someone to report on the situation on the border with Northern Catalonia and it investigated the facts and did not just stick to the official version.

Publications such as El Correo Catalán, El Diluvio and El Noticiero Universal weren’t averse to taking up positions that today we would call alarmist. Yet, the magnitude of the events ended up proving them right, and embarrassed those that followed the government line and did not do their own investigating. It is a lesson that we should remember today.

Yet, the civil authorities had few resources at their disposal, and on top of that made many mistakes. One of the most serious was covering up the events in the belief that it would avoid spreading alarm. At the start of October, Barcelona’s civil governor, Carlos González Rothwos, announced that there was no need for concern. The epidemic, he said, “is benign in nature”, a line that the many in the press repeated.

Until a week into that month, newspapers printed reports playing down the epidemic. They said that outside Barcelona, the number of ’invasions’, as they called confirmed cases, had been dropping. Yet, the same papers that sought to reassure the public also reported a large rise in the number of deaths compared with Octobers of previous years. Satirical publications like L’Esquella de la Torratxa printed descriptions that were closer to the real experience of the public than those in the serious press: people getting sick everywhere while the authorities denied it.

The price paid for the attempt to sweep the truth under the carpet was a lack of trust that gave way to feelings of anxiety. It did not help that the civil governor fled the scene between October 8 and 17. Or that while it was being reported that the epidemic was in retreat, the Health Board was “permanently” in session.

La Vanguardia on October 10 condemned the authorities for accusing the press of causing alarm, and it defended the papers for seeing the danger and denouncing it, while it accused the authorities of attacking “not the evil directly, but rather the scandalous reports about it.”

At that time, Barcelona had 641,000 inhabitants. The official statistics say some 6,209 residents died that October, when the usual figure was a little over a thousand. The figure had multiplied by many times. Meanwhile, on October 25, El Noticiero Universal reported a total of six cases of suicide.

Divine punishment

As the true cause of the epidemic was unknown, many hypotheses were printed. Some speculated that the origin of the infection was in the water or in the air, some suggested it was in the food, or due to the build up of rubbish. Naturally, there were those who attributed the flu to the lack of modesty in female fashion, such as deep necklines, while some simply said it was the result of divine punishment, as did La Comarca newspaper on October 19.

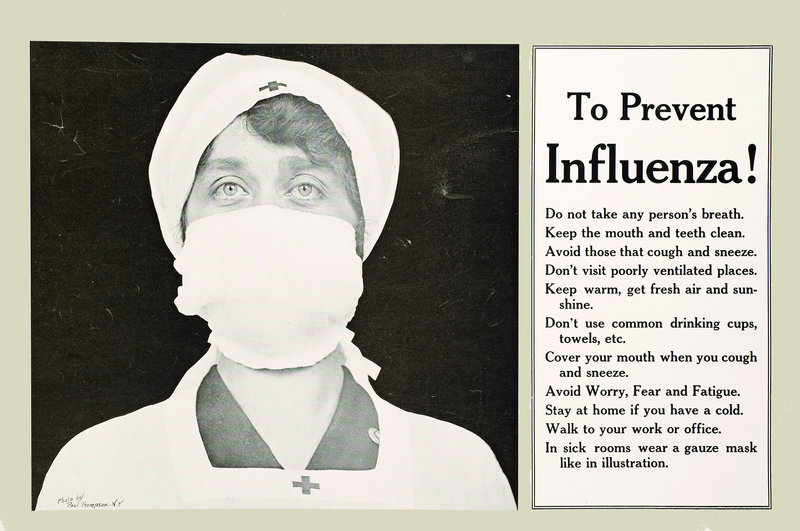

While some of the measures introduced by the authorities were reasonable, others make one wonder how they came up with them. As Turró denounced in the press: “Here hygiene is seen as a routine: isolated measures, often inefficient, are enough to satisfy those who consider themselves demanding experts. Modern hygiene is an entire system.”

The authorities were also prisoners of a persistent fantasy: that it was enough to publish an official directive for it to become reality. La Publicidad put it this way: “Many laws, royal orders, and directives from governors and mayors. All is in writing, but very little becomes reality.”

Firemen washed the streets with high-pressure hoses and the then popular disinfectant, Zotal. Residents were forbidden from sweeping the streets, in the belief that dust contributed to spreading the epidemic. People were asked to disinfect their houses. A system of coupons was introduced so that poor families could get bleach. Yet, hardly anything the authorities ordered was worth the paper it was written on. The civil governor banned the import and distribution of dusters, but few paid attention and the ban had to be reissued.

The Barcelona city council, then headed by the Lerrouxist actor, Manuel Morales Pareja, ordered that hens, rabbits and other animals be removed from balconies and rooftop terraces. Dairy goats could not be on the streets after 10am. These orders were either ignored or the animals hidden from sight. La Veu de Catalunya complained that faced with the municipal bans, every citizen “looked to see how to circumvent them”.

In the following days and up to the end of the epidemic, we find the city council constantly reissuing directives. Yet, El Diluvio complained that the local authority was unable to bring an end to the custom of “throwing rubbish into the street,” and added: “Nor has it done anything to stop the pavements being swept at all times of day.” And El Noticiero Universal added: “Rubbish is thrown into the streets despite the municipal ban. The sewers stink, the laundries disgust.”

Companys and hygiene

The epidemic did mean, even if only on paper, that for the first time the authorities began to show concern for living conditions in the city. Councillor Lluís Companys, the future Catalan president, proposed taking advantage of the opportunity to clean out empty properties and water tanks. Each household was ordered to have its own toilet. They were good initiatives but far from becoming reality. The city council gave landlords six months to install toilets, 15 days to install running water and eight days to clean out all domestic water tanks.

A commentator in Las Noticias reflected: “I ask the mayor, the governor and the Provincial Health Board where are we to find the 50,000 toilets that, at the very least, are needed...? It’s also very easy to order the closure of all wells, but where will residents get their water in eight days’ time?”

In order to raise funds to combat the epidemic, the council came up with a rent tax. El Correo Catalán wrote that the tax fell on people who were not the owners, in other words, the poor. “This sarcasm has no name,” concluded the publication. El Diluvio published more complaints. El Noticiero Universal pointed out the futility of the measure: “For all that the municipality might press, it will not have collected this million and a half for some time, in other words, probably after the epidemic has completely disappeared.”

Many post offices closed due to the disease, while villages put off harvesting the wheat. Many festivals were postponed, which in Girona did not please everyone. One editorial in the Heraldo de Gerona said: “The Sant Narcís festival must not be suspended, as it brings in major income for shops and industry and Girona.”

The civil government decreed that theatres and cinemas had to be disinfected between performances, and if they were unable to do this then they must close. The city council ordered that cinemas and theatres could only put on one performance a day, banned standing spectators – which was ignored – and urged disinfection of the premises after every two performances, an unnecessary directive because the contagion mostly emptied cinemas and theatres.

To avoid crowds, the civil governor banned dances in closed places and going to cemeteries on November 1 and 2. The florists protested, and González Rothwos added: “Flowers can be handed in to the person in charge of the cemetery, who will see to it that they are placed.” Football matches in the Catalonia championship were also suspended, although the decision was soon overturned. That Sunday, Barça and Espanyol won their respective matches. Towards the end of the epidemic, visits to the Santa Creu hospital were banned, a restriction that had been placed on all of the other hospitals in mid-October.

Barcelona University and public schools were closed, which the city council said was a “preventive” measure and no “cause for alarm”. But when it tried to do the same with private schools, the professional organisations complained because the closure, they said, would leave many teachers and their families in poverty.

Beyond that, the heads of private academies called for the reopening of the public schools “to keep children away from worse dangers in the street, cinemas and other places”. The academies closed and the protests grew. The public schools for adults stayed open because there were not many of them and, as the civil governor pointed out, the conditions of hygiene were better there than in the homes of the pupils.

Long live beer

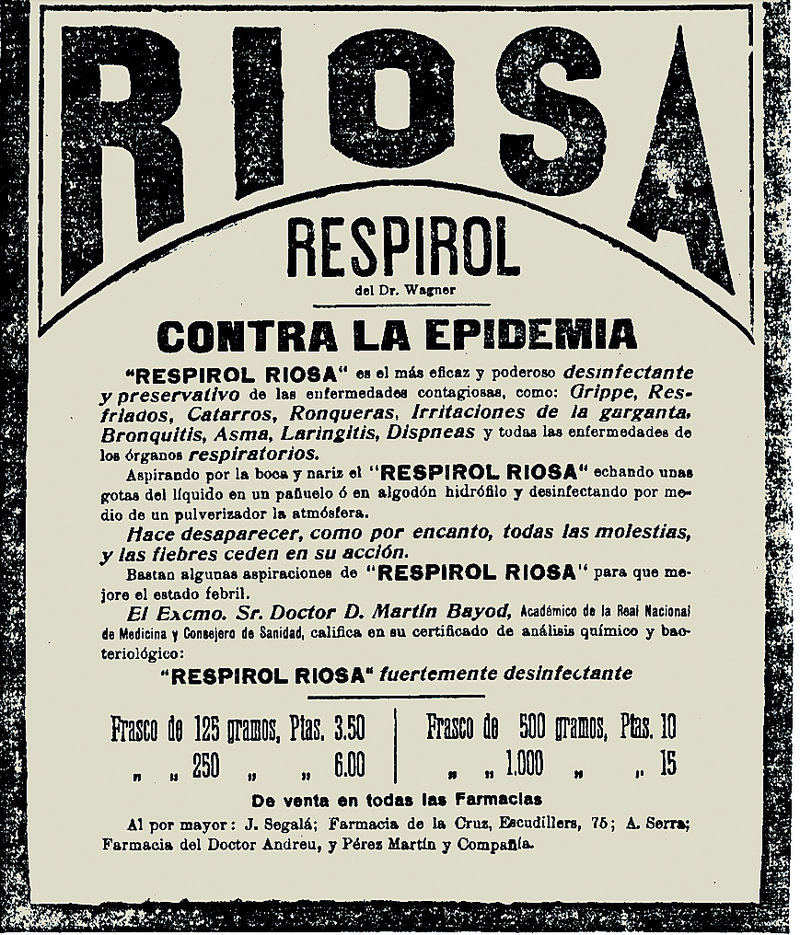

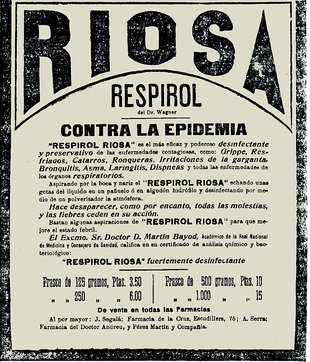

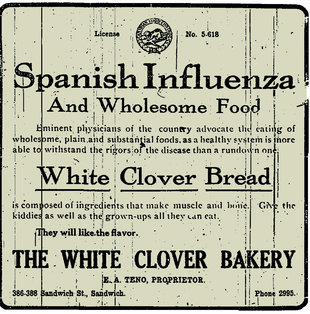

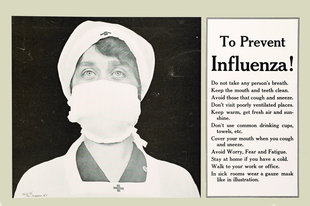

The press also printed advice about treatments. Apart from aspirin, quinine, purgatives, bloodletting and disinfectants for the nose and throat, many sufferers took to alcohol as an infallible remedy. One advert said: “Those who take beer as their only drink will remain free of infectious diseases.”

The confusion provided fertile ground for fantastical remedies. The police took one woman to court for selling an “infallible” product: “Citric acid, oregano, anise and some other drugs.” There was also a major controversy over the use of anti-diphtheria serum. We read that governance minister, Manuel García Prieto, called on Barcelona’s civil governor to end “the huge abuse of anti-diphtheria serum as a treatment for the flu”. Yet, the next day, in the Senate, senator Tomàs Maestre, who was a professor of medicine said: “Anti-diphtheria serum is the most powerful agent known that prevents the flu.” In the following days, there were calls in the press for more production of anti-diphtheria serum, and even the governance minister himself pledged to provide more funds.

Other experimental treatments were tried, such as the subcutaneous injection of one’s own blood and then “putting colloidal metal [such as gold] at the disposal of the organism”. Some doctors, basing their opinions on experience, recommended quinine salts with aspirin. Miracle cures included taking a purgative, followed by total rest, and then applying tincture of iodine between the shoulder blades. The following day the iodine had to be reapplied. According to El Diluvio, the results were excellent.

Even though all medicines used proved useless, the epidemic caused shortages. Not long after it broke out, the civil governor ordered an inventory of all drugs with the aim of “banning”, if necessary, “the new release of medicines given the scandalous rise in prices that have been seen”. Obviously, the order was disobeyed. The complaints about the high prices of medicines went on until the end. The pharmaceutical firms protested, and the civil governor repeated the original orders.

How was the calamity to be fought? From the start, Turró said: “The secret of victory is in the perfect health and nutrition of each individual, who should diligently take care of any indisposition the moment it is noted.” On this recommendation, which the authorities backed, the commentator Ariel wrote in La Vanguardia: “This thing [of nutrition], for the poor is a problem that is as difficult to solve as the illness itself.” Other recommendations, such as avoiding “concentrating sufferers in small houses without hygienic conditions” or that each ill person had to be kept in “a single room”, or if not, separated by “a wall or sheets hung between beds while the room is constantly ventilated” seemed like a joke, as many people in Barcelona were forced to live in unhealthy conditions.

There was much criticism of the handling of the crisis. One of the few who never lost sight of the problem was Turró, who in an interview in La Publicidad on October 15 stated: “No one either in Sweden or Switzerland blamed the authorities for the disaster; that would have been to call for measures against an aurora borealis.” Turró also said that instead of criticising the authorities so much, it would be better to help those who were ill, and concluded: “It is much more comfortable to blame the neighbour opposite for the evils that affect us.”

Cemeteries overwhelmed

As the deaths climbed, the crisis impacted the funeral services, which complained of a lack of coffins. In an ineffective effort to make burials efficient, the council ordered priests not to visit houses or accompany funeral processions. Due to a lack of staff, the local authorities mobilised the militia to drive hearses if the driver was ill. The Red Cross set up a service to collect cadavers from poor families, and the bishopric published statements absolving itself of blame.

The order also went out not to ring church bells for the deceased, as it was believed that it would spread alarm. Yet, El Diluvio said that church bells could be heard ringing at all hours, and that the noise bothered people who were ill. Due to the depressing sight of coffins piling up in the open air at Morrot station, the civil governor asked the Red Cross to put up a tent to hide them.

Newspapers like El Correo Catalán, La Vanguardia, Diario de Barcelona, El Diluvio and El Noticiero Universal printed the addresses of houses in which deceased people had spent too long without being taken away. “If it were not for popular initiative, the disinterested collaboration of citizens, cadavers would pile up in houses,” said El Correo Catalán. The newspaper railed against the funeral monopoly: “The coffins arrive late and in bad condition; when the cadavers are in a state of decomposition it leads to horrific scenes.” We also read about how 400 locals protested on carrer Sant Domènec del Call against the deficiencies of the funeral services and because the council had not disinfected the house of a deceased person. For the Carlismist El Correo Catalán, the conclusion was clear: “Barcelona is a Bedouin encampment, a dung heap, a filthy pigsty, where residents should not have to live.”

Barcelona, like all the cities in the world affected by the 1918 flu, found itself in a health crisis because it was not prepared for the epidemic. The ineffectiveness of the health measures implemented, the orders from the public powers that were never applied, the chronic lack of services and resources, and the lack of discipline shown by the population all contributed to making the crisis worse. Fortunately for all of us, conditions have changed a great deal in a century.

feature