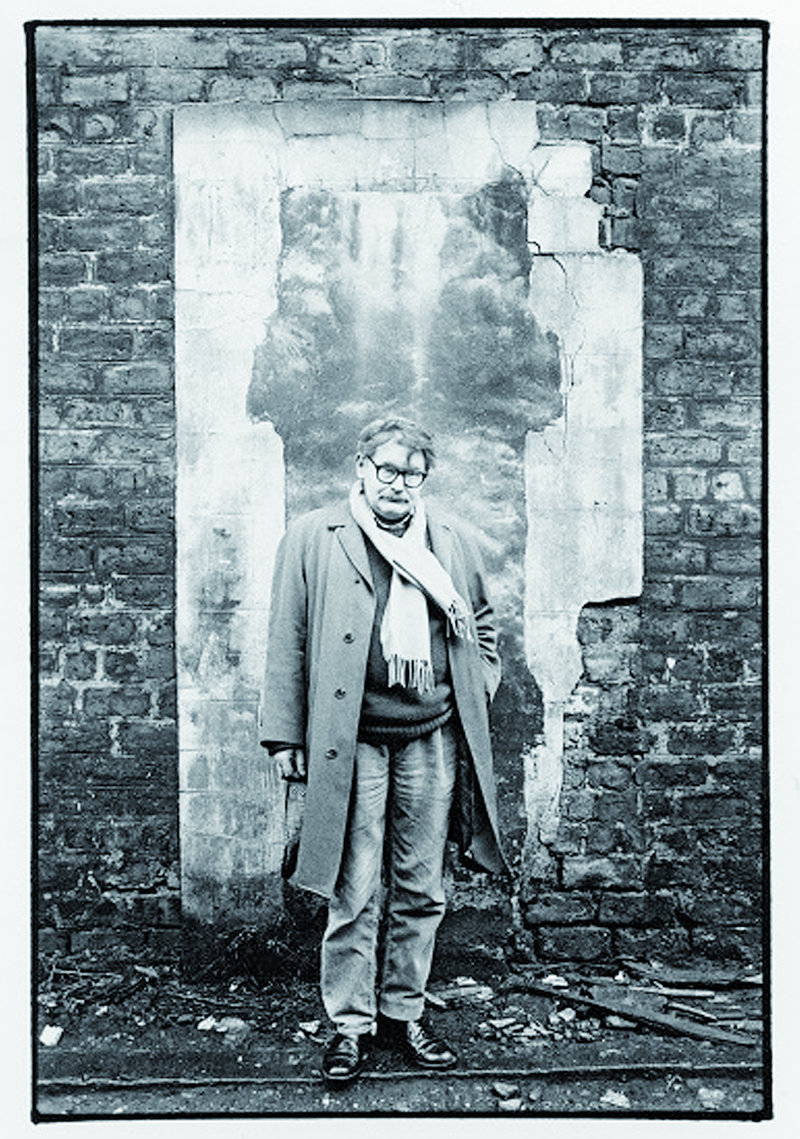

Alasdair Gray

28 December 1934 - 29 December 2019

in the early days of a better nation

“When I was 19 or 20 I went to a reading Alasdair Gray gave in Aberdeen, and I came away from that reading knowing that anything and everything were possible in writing. Scottish writing was in revolution and Gray was the heart of a literary renaissance which revitalised everything.” Ali Smith

The eulogy of Ali Smith, one of Britain’s finest writers, is characteristic of the outpouring of grief and admiration for Alasdair Gray, who died in the decade’s dying days, aged 85. His 560-page first novel Lanark, published in 1981 after 25 years gestation, blew open the gates to a golden era of Scottish literature. Like Joyce’s Ulysses, wrote the Evening Standard; “the greatest Scottish novel since Walter Scott,” Anthony Burgess said. Lanark, a mixture of coming-of-age angst, autobiography, fantasy, social realism, science fiction, analysis of mental breakdown and political critique was something quite new - though it had firm roots in modernism and reached back to nineteenth-century artist-writers like Williams Blake and Morris. It is not only Gray’s friends James Kelman and Agnes Owens who owe a debt to Gray, but a long list of writers: Ian Rankin, AL Kennedy, Irvine Welsh, Val Mcdermid, Ali Smith, Iain Banks, Janice Galloway, Liz Lochhead… almost anyone who has written in this Scottish Renaissance.

Gloomy labyrinth

In 1992 Gray published a pamphlet “Why Scots should rule Scotland”, with a vision of a socialist, independent Scotland based on working-class liberation and culture. Yet his political impact was greater than this directly political polemic. Though the influence of literature and culture is not measurable in any precise way, Gray gave Scottish writers and artists a confidence that affected the whole political climate. As Ali Smith says, anything seemed possible. Even that Scots might rule Scotland.

Nearly all Gray’s work is worth reading, but Lanark is his masterpiece. It is a surreal work based on a very concrete evocation of Glasgow, a “gloomy, huge labyrinth.” If it is true that a place needs a great writer to create it before it can take form in the imagination of its own citizens, as Dickens’ London IS the London of our minds, then Gray created Glasgow in Lanark. He caught the dark beauty and the roughness of the city, never more so than in its opening pages, set very concretely in a 1950s cinema coffee-bar, but at the same time suggesting a future of dictators and gangs.

I was lucky to see and hear Alasdair Gray in 1992, at the British Institute in Barcelona’s carrer Amigó to celebrate the publication in Spanish by Anagrama of Something Leather (in the days when the British Institute had a budget to promote writers). Fat, white-haired and uncombed, his eccentricities extended to his manner of speaking. He would wander off on numerous tangents, burst out laughing, suddenly cut short the guffaw with a high-pitched “Sorry, sorry”, then at once enter another line of argument, at first stuttering then rapidly spitting out a sentence with fluency.

His novels are similar, with debates, tangents, politics and humour expressed with artful simplicity. Not just humour, but joy - he loves jokes. He is an entertainer. In his best novels, Lanark (1981), 1982 Janine (1984), Something Leather (1990) or Poor Things (1992), Gray ties all these elements together in a great story. There are many other books: poems, short story collections and the monumental Book of Prefaces (2000), all decorated with Gray’s drawings and design. His books, with their art work, were worth all the extra expense, delays and headaches to his publishers. They are themselves art objects.

No pornographer

Gray also painted several major murals across Glasgow, much mocked in their time but revered today. There are recognisable motifs and images in both books and murals: large-breasted women; skulls; naked men; bearded men; self-portraits; doves and dogs; faces with a precision of line-painted drawings, one could say--; and a figure at the end of his books holding a sign saying “Goodbye”. At times, the straightforward writing style, benevolent written and drawn portraits, and jokes can seem twee, even tiresome to some. If so, it’s a small price for his commitment to engage with his readers. He even endearingly printed negative criticism, such as this by Peter Levi on 1982 Janine: “I recommend nobody to read this book… sexually oppressive, the sentences are far too long and it is boring… hogwash.”

The Book of Prefaces is a collection of authors’ prefaces from the seventh to the twentieth centuries, with glosses by Gray. At 640 pages, it is a history of “the literature of four nations” - United States, Scotland, Ireland and England -, as Gray puts it. This is a kind of literary criticism at its best: originating outside the academy, erudite, aware of books’ times and their authors’ social origins and wanting to entertain.

In the 1980s he was often attacked as a pornographer, for Janine 1982 is about a man with sadomasochistic fantasies. It is a mistake. He is discussing Scottish puritanism: sexual frustration (and the rational opposition to it, which understands but does not prevent it) runs throughout his work. Whereas pornography merely confirms the oppressive power structures of the world, Gray looks at pornography in order to unveil those oppressive power structures. He has great orthodox writing qualities: energy, pace, characterization. He is witty and accessible. But what brings everything together to make these technical abilities so important are his politics: class, national and sexual politics.

He will be remembered as a powerful and kindly cultural presence, devoted to a literature that is the opposite of much British fiction, with its “huge silences and absences about the lives of most people.” One of Gray’s mottoes was: “Work as if you live in the early days of a better nation.” It’s advice applicable to us in Catalonia, as many things Scottish are these days.

obituary alisdair gray