The “SLOVENIAN WAY” to independence

Some observers have drawn parallels between the current political situation in Catalonia and Spain, and that of the Eastern European republic’s efforts to break away from the Yugoslav federation in the 1990s. But is the comparison a valid one?

In a room dedicated to the 20th century in the National Museum of Contemporary History of Ljubljana, the capital of Slovenia, there is a photograph of Slobodan Milosevic, then president of the Socialist Republic of Serbia, federated to what was once Yugoslavia, raising a card to vote “No” during the 14th Extraordinary Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, held from January 20 to 22, 1990.

The significance of this photo and that of the vote, is that it was the response of the influential Serbian politician to a proposal made by the delegation of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia, also federated in this mosaic of disparate republics that was Yugoslavia, calling for reforms, including multi-party democratic elections, which meant breaking the stunted Yugoslav political structure that had held since the foundation of this socialist state by Josip Broz Tito at the end of World War I.

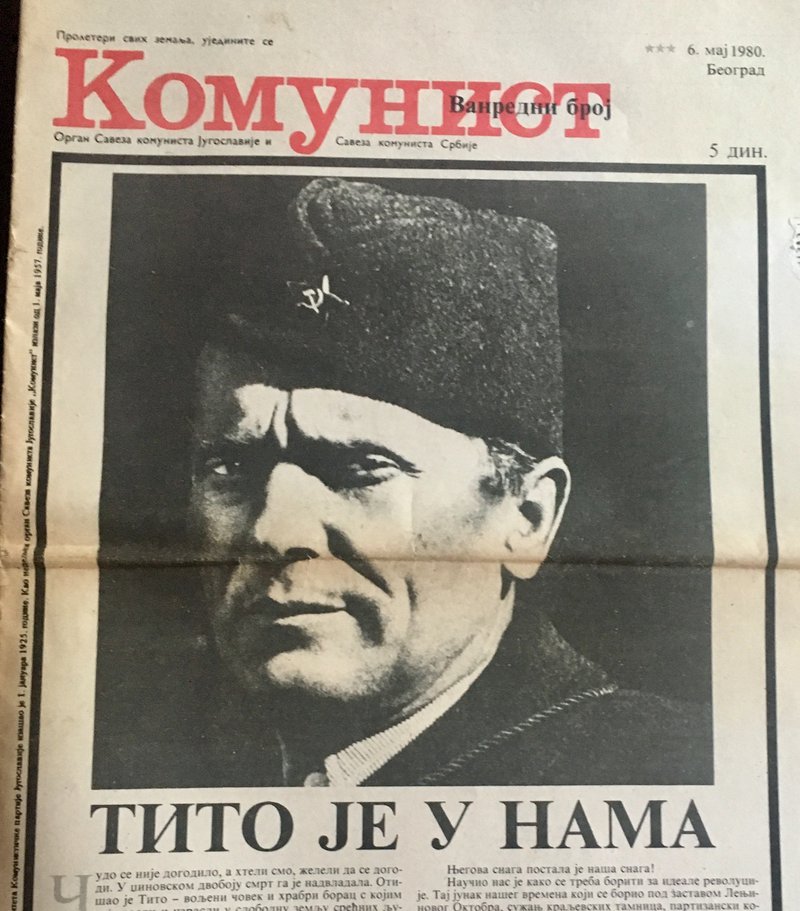

Tito had died 10 years before, precisely in Slovenia, after a long illness, and his disappearance, together with the economic crisis of those years, increased Yugoslavia’s debt, produced a decrease in living standards, a shortage of basic products, and uneven development between the different republics, in addition to new ethnic tensions hidden during the time of Tito.

Slovenia, the most ethnically homogeneous and relatively more developed republic, close both culturally and sentimentally to democratic Europe, saw no future for the “Titoist” conception of the Yugoslav federation and much less for Milosevic’s aim of a more centralised political and economic structure in which Serbia would, of course, be the dominant republic. In fact, a third of the delegates at the Congress were Serbs, a percentage roughly equivalent to the total Serbian population in the country as a whole, thereby ensuring that Milosevic secured a good proportion of favourable votes from among the six confederate republics.

Milosevic’s blunt “No” to the Slovenian reformist proposals, which Croatia, another of the Yugoslav republics, had also supported, had an inevitable outcome: Slovenian delegates felt despised and left the Congress en masse, something the Croatians also did when Milosevic wanted to impose his policy and continue the meeting and the voting despite the absence of delegates from Slovenia.

Eighteen months later, Yugoslavia ceased to exist after more than 80 years as a state and 45 years of socialist status, and Slovenia gained its independence.

In the current debate on the political future of Catalonia within the Spanish State, the example of Slovenia, or what has come to be called “the Slovenian way”, has been brandished by pro-independence politicians as a path to separation from a state that, they say, does not satisfy their political and economic aspirations within the present structures.

There could be a parallel between Milosevic’s “No” to the Slovenian proposal to give more power to the republics and launch deep political reforms and the refusal of the former Spanish prime minister Mariano Rajoy to the request by Catalan president Artur Mas regarding a new fiscal pact for Catalonia at the now famous and iconic meeting held at the Palacio de la Moncloa seven years ago. That meeting set the stage for a new campaign of Catalan claims, resulting in the current territorial and constitutional crisis in Spain.

For the moment, if there is any parallel between the two situations, it ends there. What came next has differed, at least until now.

Slovenia stubbornly insisted on following its path outside the state to which it belonged. On December 23, 1990, two million Slovenes were called to vote in a referendum to decide whether they wanted an independent state (“Da”) or not (“Ne”) and the result was unequivocal. With a turnout of 93.2%, 88.5% of the voters chose the option of continuing their lives outside the state they had belonged to, with some changes, since the end of World War I in 1919.

In view of this result, the Slovenian authorities proposed to Belgrade the peaceful dissolution of the Federal Socialist Republic of Yugoslavia to facilitate divorce negotiations. The federal authorities rejected the proposal quickly and vehemently and launched all kinds of accusations against Slovenian separatists. The tension was increasing. The unthinkable, an armed conflict within the borders of civilised Europe, was glimpsed on the horizon, although at this point far from the catastrophic dimensions it would ultimately reach.

In Slovenia there were barracks of the so-called “Yugoslav People’s Army”, controlled from Belgrade and therefore subject to the orders of a federal government opposed to Slovenian secession. But Ljubljana also had indigenous Territorial Defence Forces, the only military force available to the Slovenian authorities, which was quickly reinforced and equipped.

Initially, the European Union refused to recognise Slovenia’s independence because it had been declared unilaterally. But when hostilities began between the federal army and the local militia as soon as Slovenia proclaimed its independence on June 26, 1991, Brussels did everything possible to reunite the two sides and prevent the extension of the conflict, something that at that time seemed achievable.

The Agreement of Brioni, an island near the Croatian coast, ended the so-called “Ten-day war” between the “Yugoslav People’s Army” (YPA) and the Slovenian militias. The former, which were surprisingly weaker in the conflict, pledged to cease their attacks, while the Slovenian authorities pledged to do the same and establish a three-month moratorium on their policy of advancing the country’s independence.

The “Ten-Day War” produced 75 deaths: 44 in the YPA, 19 were Slovenian fighters and the rest “foreigners”. Politically, the conflict exacerbated an already insurmountable gap between the Ljubljana executive and that of Belgrade, and obviously among the respective populations.

By the time the moratorium expired, Croatia had also embraced independence and Serbia was preparing an aggressive defence plan for its ethnic minorities scattered throughout all the republics because it considered them vulnerable in view of the historical precedent and nationalist fervour fuelled by the conflict. These Serb minorities challenged local authorities everywhere and defended what they deemed threatened territories and cultural rights. The prejudices and historical grievances came to the surface again. The break-up of Yugoslavia through an ethnic conflict that unleashed unimaginable brutality had begun. But this time the conflict did not last 10 days but 10 years. The Balkans became rivers of blood.

There are also some politicians in Spain who have established another sinister parallel between the Spanish situation (“the Balkanisation of Spain”) and the Yugoslavian bloodshed. That seems to be far-fetched, if not provocative. If the Balkan conflict proved anything, it is how easy it is to awaken sleeping demons, fuel hatred, and let demagogy, falsehood, racism, intolerance and cruel medieval savagery among humans take over the minds of the people.

We should learn from history. Events such as those in the Balkans in the 90’s should be prevented from happening again there and elsewhere. And that requires effort on all sides.

feature The Balkans revisited (1)

feature The Balkans revisited (1)