When garlic breath is haute literature

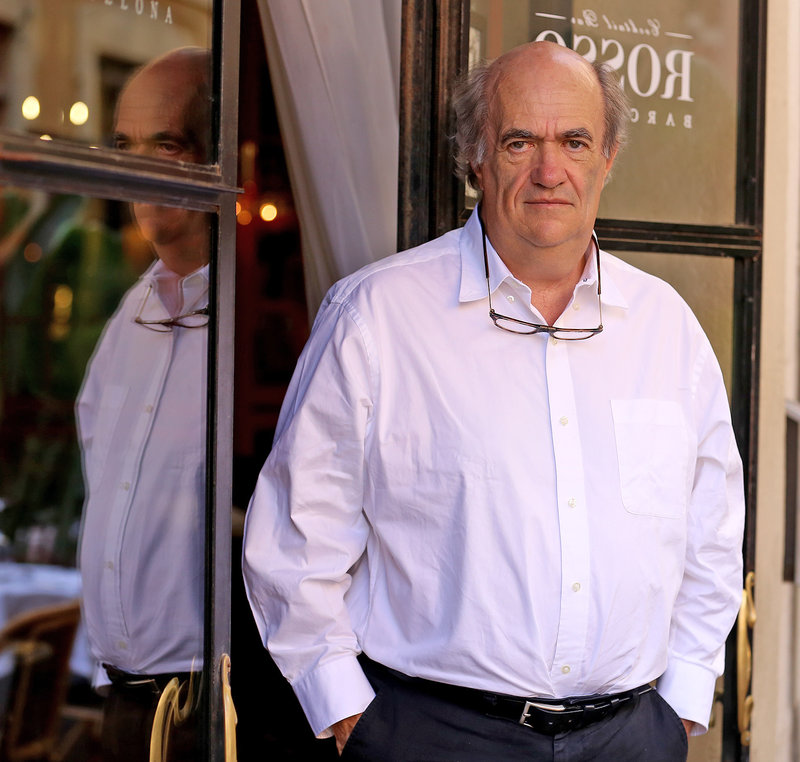

In a Catalan anthology of his stories, Mares i fills, Irish narrator Colm Tóibín speaks of family, sexuality and exile

In the story Barcelona, 1975, which has a strong autobiographical component, Colm Tóibín writes: “His mouth had a taste that I had never found before. It was garlic. Even now, if I ever notice a touch of garlic on someone’s breath, it conveys an erotic charge, a feeling of pure and simple pleasure.” “That garlic breath may be erotic or an aphrodisiac is not opinion, it is fact,” said the Irish author, laughing, and covering his face with his hands a few days ago. It would appear that, rather than decreasing, this sexual connotation of garlic has increased over the last 44 years.

Barcelona, 1975, in which Tóibín relates how he met Ocaña in Plaça Reial, is one of the 13 stories in Mares i fills, an anthology that brings together a selection of two other books, The Empty Family and Mothers and Sons, published in Catalan by Amsterdam (with translation by Ferran Ràfols), with a prologue by Andreu Jaume, and in Spanish by Lumen (translated by Antonia Martín).

Colm Tóibín (Enniscorthy, 1955) is one of the great modern authors of English literature, both inside and outside Ireland. He divides his time between New York, Los Angeles, Ireland and, for much of the summer, Farrera de Pallars, where he has had a house since the 1990s.

His work includes novels, short narratives, essays, theatre and literary criticism. These stories reveal everything from an admiration of Henry James, his most important confessed influence, to an exploration of uprooting and returning home, homosexuality, the Spanish state at the end of the Franco regime and, of course, the relationship between mothers and sons. All in a style that barrels from social realism to the most sublime subtlety, and includes the emotional elements and ellipsis that have characterised Tóibín’s literature to date. The work of this regular candidate for the Booker Prize — nominated three times, he has never won it — has been translated into over 30 languages. In Catalan, Amsterdam has published Brooklyn (2010), El testament de Maria (2014), Nora Webster (2016) and La casa dels noms (2017).

What brought a young Irishman to Barcelona in the final years of the Franco regime? “I had some Irish friends who had spent a few years teaching in Barcelona and they told me it was easy to find work as an English teacher. I was 20 years old and had been studying at university for three years. It was time to decide what to do in the immediate future and, quite quickly, I decided to come to Barcelona,” he explains in very comprehensible Catalan, wrought in Pallars, where, as mentioned, he has a house. Since Catalans tend to change to Spanish when faced with foreigners and stick to Catalan among ourselves, Tóibín soon saw that what Catalans said to each other was more interesting and learned the language.

“When Franco died, a teacher friend took advantage of the holiday to go away with his wife and saw a beautiful place, with empty houses, in Farrera de Pallars”. Tóibín went there in March 1976 and in the 1990s went back and bought an abandoned barn there before renovating it.

This is the setting for the start of the story Estiu del 38. “A historian told me that he invited a fascist general to La Pobla de Segur in the eighties to locate the spot where certain battles had taken place and, walking down the street, the general crossed paths with a woman, also old, from the town, and they greeted each other in a very friendly way. In addition, I knew that during the war, in the summer of 1938, there were National soldiers who would go to play the guitar and sing and drink wine on the banks of the river and that, little by little, the young people of the town joined the parties, because the men had fled [the war].” And so he brought the two situations together in prose, turning them into literature with his narrative ability.

“Everything starts with something someone tells you, but you have to change it until you make it yours. You have to sit down and write when a thought, a phrase or something someone has told you changes and starts to have a rhythm to it, when you realise that what you want to explain is there. And that happens suddenly, in a way that you can’t control or force. That’s when you have to work hard,” he says. “I always go round and round the same subjects, in a circular way: family, sexuality and exile. And nothing else. Maybe identity, but that’s part of sexuality.”

These are descriptive and conclusive stories. No final twists. Stories with narrative musicality, often with a specific music, as in Una cançó, in which we witness the pain of a young man who hears a woman sing in a pub and realises it is his mother who left him as a child. Without knowing what song it is, we listen to it, we feel it beat.

And this way of narrating he partly owes to Henry James. Although without natural talent, an influence means nothing. “Henry James changed the theory of the novel. Before him, the novel was about its architecture, but the most important thing is the point of view, you have to choose the point of view of a person, a character who has emotions, who can remember, think, who can do everything... To write a story or a novel you can’t enter the head of all the characters, you have to choose one,” he explains.

Political view of Catalonia

In July 2014, Tóibín said in an interview that it would be hard for Catalonia to become independent because Spain and Europe are too strong. Is that still the same? “Yes. It’s complicated. Although what no one in Europe understands is that the politicians are still in prison. If it were in Azerbaijan people would understand, but not here,” says Tóibín, although Europe has done little to correct an undemocratic situation.

He is more positive with his view of the language, although the latest statistics contradict him slightly. “What has happened here with the language is a miracle. In Ireland, people don’t want to speak Irish, but here language immersion has been a success. The problem is that there’s a huge difference between the city of Barcelona and Vic, or El Pallars, or Girona, where most people speak in Catalan. Barcelona has always been a melting pot of cultures, where there are Catalans, but also Pakistanis, Andalusians, Peruvians... Nationalism is an emotion, and other things too, but it is based on an emotion that outsiders do not feel. And this can become a problem. But Barcelona must remain as it is: a melting pot of cultures.”

INTERVIEW