Close to the truth

This collection of fourteen tales set in Barcelona is one of a long-lasting O.U.P. series: Paris, Berlin, Amsterdam and Lisbon, among several others, precede it. The collections are aimed at giving cultural tourists a literary background to the cities. They are tales for holiday-makers, readable in snatches

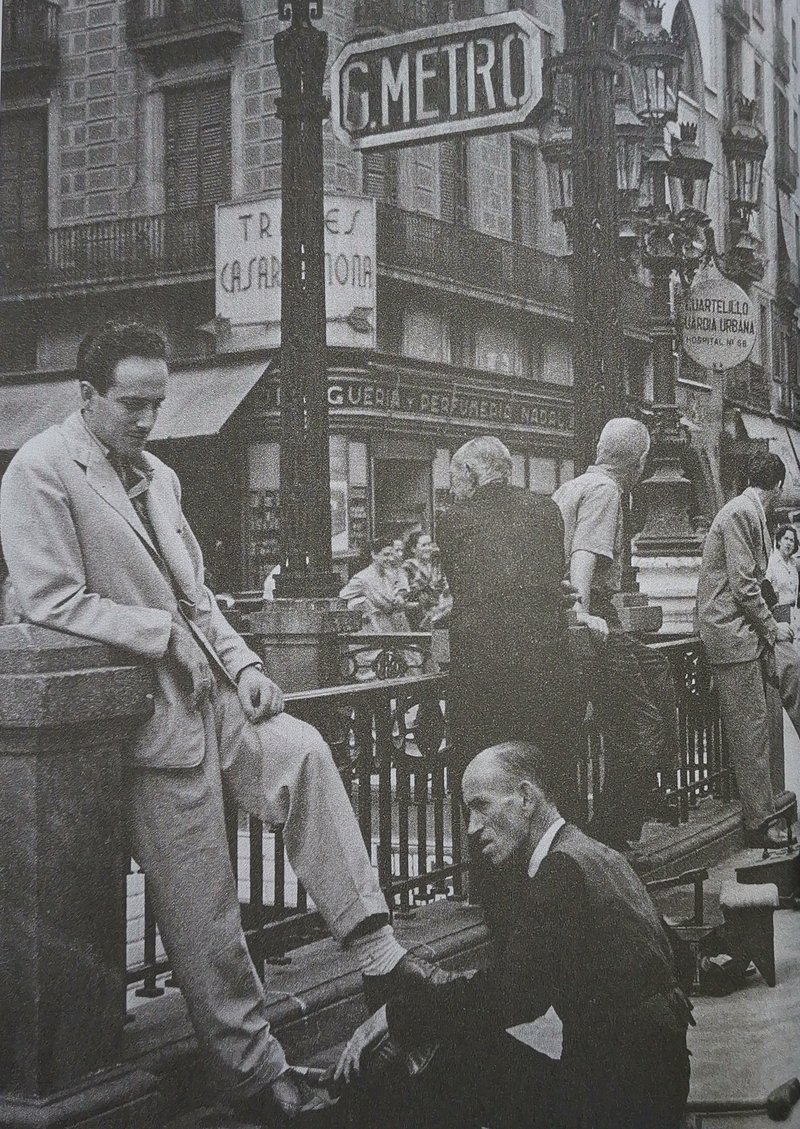

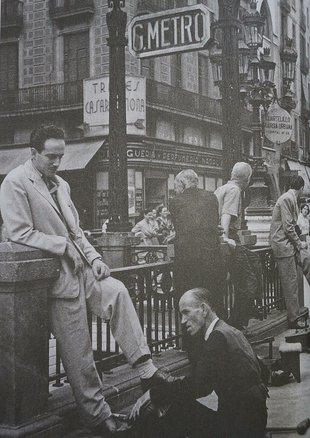

Barcelona Tales has a black and white photo accompanying each story. Two introductions, by editor and translator, give context to the tales. A list of other books about the city is supplied. A map of Barcelona shows the tales’ locations. It is a beautifully produced soft-cover book.

Not all are short stories. The book opens with Cervantes’ description of Don Quijote visiting Barcelona. The Don laps up peoples’ adulation as he walks the streets without realising that he is carrying a sign on his back saying “THIS IS DON QUIXOTE”, yet he is innocent in both his pleasure and, later, fury at the printer publishing a book about him without permission. Don Quijote rages about the author: “…he’ll get his comeuppance soon, because fiction is enjoyable only when it comes close to the truth…”, thus expressing 400 years ago the subtle relationship between fiction (lying?) and truth (reality?).

The stories evoke very specific parts of the city. Teresa Solana’s “Dead Time” is the most concrete, with a tale set around the Ninot market on the Left of the Eixample that details the smells of the foods and spices, and dwells on “that bourgeois neighbourhood where common-sense grid-iron streets coexist with the flamboyance of surreal modernist façades, a marine horizon, and the silhouette of the mountain”. Her protagonist Soledad knows but does not want to know the terrible truth about her husband. The woman wants Barcelona life, her routine life, just to run on without collapse or radical change. Like all of us, but impossible! This is a city (like most) of war and upheaval, both public and private.

In “Transplanted” Narcís Oller, founder of the modern novel in Catalan in the late nineteenth century, tackles the drama of a village baker who emigrates to Barcelona, loves the city’s glamour and bustle, but suffers its loneliness and finds on his return to the village that he no longer has a place there, either. Josep Pla, Montserrat Roig and the Peruvian Alfredo Bryce Echenique have stories that perhaps do not represent the best of their authors. Montserrat Roig’s, with the suggestive title, “A Brief, Heart-Warming Story of a Madame Bovary Born and Bred in Gràcia, Following our Best Principles and Traditions”, bamboozled me at first. Greater concentration reveals an experimental, modernist story interweaving the narrator’s Bovarian frivolity and the death of her grandmother. Not even seeing the dead and wounded in the 1893 bombing of the Liceu dents her egotism.

Living Writers

Juan Marsé’s tale (“A Detective Story”) of lost kids playing among the ruins in the aftermath of the Civil War (though the fine photo accompanying it is of the beach, not the hills where the story is set) strikes the themes of much of his literature: nostalgia for broken futures, the cinema as escape, children traumatised by the war, cops everywhere, women driven by poverty to prostitution and men to suicide, fathers absent in jail or exile. I am prejudiced in his favour (literarily, not politically). Marsé’s fine story should stimulate readers to look for the novels of one of the greatest living Catalan writers. In the subtle story (“Three Steps”) by Miquel Molina that follows, the novel-loving main character visits a typical Marsé scene and finds it is now overrun by tourists. The occasional grimy post-war bar has given way to restaurants now serving “some kind of exotic cuisine.” Marsé himself then appears, warning the narrator that his (Marsé’s) book is just fiction. Hero-worship is unhealthy, but, as Cervantes noted, good fiction “comes close to the truth”.

Another pleasure of an anthology is to discover writers unknown to the reader. C.A. Jordana’s “Blitz on Barcelona” is the book’s Civil War story, but one that defies expectation. This is no brutally realist story of bombs and slaughter, as the title suggests, but rather three sketches: of the moon on a night enemy planes are flying, a hospital and a bar. Its originality made me turn at once to the mini-biographies of the authors at the end to find out more about Jordana.

There are several other living writers, younger than Marsé (now 86), toward the end of this chronologically ordered book. Jordi Nopca weaves a tale of industrious migrants from China who become involved with difficult neighbours after opening a bar. Najat el Hachmi has another tale on the conflicts of migration (“The Sound of Keys”). Two young North African women move to a Barcelona flat, fleeing from their parents and four brothers in a Catalan town where the women have to do all the work. As always a fine, intelligent writer, she draws out the differing reactions of the women to their new-found freedom in this second migration.

In another story of migration, Empar Moliner, a passionate contributor to Catalunya Ràdio afternoons as well as a writer of acid stories, subdues her usual exuberance for a dramatic report on class and exploitation. She describes a “market” in a convent where the upper class can hire South-American maids and carers for about 600 euros a month.

The utterly convincing obnoxious protagonist of Quim Monzó’s “The Boy Who was Sure to Die” exemplifies how low an opinion this great short-story writer has of humans. Loneliness in the modern city and untameable selfishness are the themes of his deeply heartfelt stories about heartless people. Jorge Carrión’s cameo is a nice reflection on sounds and silence: dead languages, a mute cat, parrots that go dumb in old age and loquacious taxi-drivers who don’t.

One can always think of some omissions when reading an anthology. Where is so-and-so? Why wasn’t this beloved story included? There can be little complaint, though, about these fourteen tales, set in different areas of Barcelona, from the Montjuïc to the Carmel hills, from the Rambla to the Eixample and Gràcia. They reveal how this industrial port city has been and is a magnet for migrants. They show the class divisions between areas. They trace, too, the development of modern Catalan literature in both Catalan and Spanish. Cervantes is the richest of aperitifs, but the main menu starts, after centuries of decline and repression, with the nineteenth-century return to a vigorous literature, an artistic renaissance accompanying Catalonia’s political and economic renaixença.

book review

Editor and translator

Helen Constantine has edited all the Oxford University Press series of city tales. She is a translator from the French, too, with Balzac, Flaubert and Zola among her many credits.

Peter Bush is a distinguished translator from Spanish and Catalan to English. Awarded several prizes for translations and services to Catalan literature, in recent years Peter has brought many Catalan classics into English: Pla, Mercè Rodoreda, Prudenci Bertrana, Joan Sales and Emili Teixidor, along with a number of contemporary writers, from Teresa Solana, Quim Monzó and Francesc Serés to the endurance runner Kilian Jornet.