A new world in their hearts

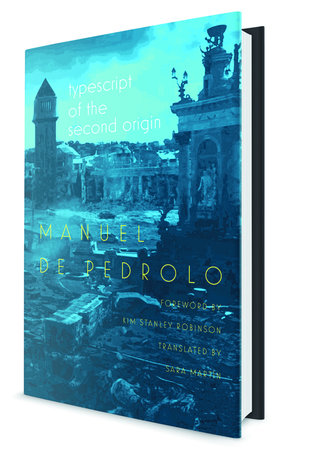

This short novel is like a series of hammer blows. Arranged in five notebooks, each notebook ordered in numbered paragraphs, with every paragraph starting ‘And’ to drive the narrative forward, the book strikes the reader with force, pace and a clear stream of prose

Typescript of the Second Origin (Mecanoscrit del segon origen) is Pedrolo’s best-known book. Alba and Dídac survive the attack of flying saucers that reduce their village to ruins and kill all humans except them. Fourteen and nine years old, they have to organise their survival. Their parents are buried under rubble, their neighbours and school-friends are dead, there are no phones, no TV and no house left standing. They camp in the woods to escape infection from corpses. They raid shops for tinned food and medicines. They acquire fire-arms from the police station. Alba is a girl, then a woman, of great resources. In each ‘Notebook’ she grows a year: starting at 14, she ends up at 18.

Pedrolo’s panorama of total destruction by something like a neutron bomb is ferocious. The book is often presented as science fiction for children and nowadays is taught in schools. It is, rather, a book about children, but for adults: both because of the horror of the situation and because Pedrolo’s purpose is to write an adventure story that also pushes his readers to think.

Gradually Alba and Dídac overcome their fear and disorientation and begin to create a new world, based on solidarity and satisfaction of basic needs. They find a large sum of money, but private property is no use. They release Dídac’s caged goldfinch. He loves it but learns to love its freedom more. Alba is white; Dídac black. In the new post-destruction world, he no longer suffers racism.

Alba has a mission: to conserve for future generations all the books she can find because they contain the sum of humanity’s knowledge (even though they might contain dangerous superstition). The children dare to begin to feel happy. The book becomes a song of freedom. Alba reflects (Paragraph 14, Notebook 2):

“For sure she couldn’t hide the ruins from Dídac, but she wanted him to feel they were not the demolition of an old world, but the materials with which to construct a new one.”

She sounds like Buenaventura Durruti, who had no fear of smashing capitalism, for: “We carry a new world, here in our hearts.” But unlike Durruti, Alba believes in conserving the culture of the past.

Mother of humanity

Pedrolo is telling an alternative creation myth, a rebirth of humanity without class society, religion or racism. Mass destruction opens the way to a second start. Not all is roses, though: this science-fiction fantasy is a tough, realistic story. The children have to kill an alien so as not to be killed. On a journey by boat from Barcelona along the coasts of what once were France and Italy, they meet three men, crazed survivors set on raping Alba. The children kill them, too. They meet a woman maddened by the death of her child and world.

They themselves have decided that, when Dídac is old enough, they will have children. Thus, poses Pedrolo at the end, Alba becomes the mother of humanity, a new non-religious, non-subordinate Eve.

The novel is now 45 years old and was published when the Franco regime was in its death throes. It was a fitting time for a book on a new world being created out of the disappearance of the old; on Catalonia rising from the regime’s attempt to wipe out its identity. Some references date it: the emphasis on libraries and books or the male gaze of Pedrolo dwelling on Alba’s breasts and tight white bikini like Ursula Andress’ in the film Dr. No, a famous image of the time.

Typescript of the second origin is an adventure story, told in Pedrolo’s direct prose, lucid like flowing clear water. And the adventure is also a parable of freedom and love in a new world. I asked Anna Maria Villalonga, the coordinator of Pedrolo’s Centenary Year in 2018, to sum up the novel:

“Typescript of the Second Origin represents Pedrolo’s desire to bring normality to Catalan literature by introducing genre fiction. It is also a very modern polemic against racism and prejudices and a defence of books, culture and the central role of women. Not in vain does Pedrolo place in the hands of a woman the rebirth of destroyed humanity.”

book review

book review

Dangerous quality Translation

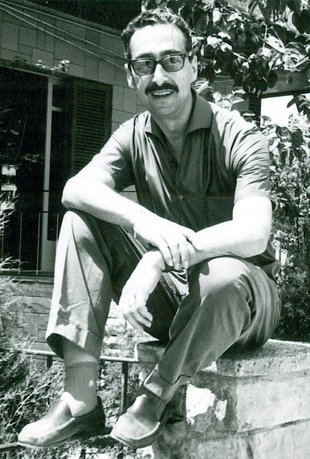

Manuel de Pedrolo i Molina was born in 1918 into a family of the minor rural nobility and brought up in the castle of Aranyó (Lleida). In 2018, year of his centenary celebrations, a biography by Bel Zaballa was titled La llibertat insubornable, Incorruptible Freedom. That sums up the life of Pedrolo, a writer who was a revolutionary and fighter for Catalan independence from the Civil War, when he joined the anarchist CNT, to his death. In the war he worked as a teacher and fought with the Republican army on the Fraga and Figueres fronts. In the 1940s, after being forced by the dictatorship to repeat military service in Valladolid, he scraped a living at many jobs, among them for an investigation agency, which makes him and Dashiell Hammett just about the only crime writers to have actually worked as detectives.

Pedrolo’s reputation is high: he wrote both popular fiction and highly literary books, always devoted consciously to the recovery and development of literature in Catalan. His first published books, from 1949, were poetry. Between then and his death from cancer in 1992 he had over 120 books published, most of them novels. These were in a variety of genres: thrillers, science fiction, crime, psychological dramas. He wrote plays, too. The censorship of the Franco regime meant his books were repeatedly rejected for “Catalanism, political opinions, sexual immorality and indecorous language”. In 1959 one censor honoured him by forbidding publication of a novel because it was “dangerous… due to its high literary quality.” Censorship problems meant Pedrolo found few publishers willing to risk taking him on. He was not prepared to seek the easier paths of self-censorship and/or publishing in Spanish.

Pedrolo was also a busy translator, in the 1950s mainly poetry from Italian, French and English. In the 1960s he edited the famous La Cua de Palla list of translations of North-American and French crime fiction into Catalan. Their style chimed with Pedrolo’s own literature, distinguished for the clarity of its language and for its realism of detail, however speculative and experimental some of his books are.

In the 1970s, with the dictatorship wilting then defeated, Pedrolo’s own books were published copiously: 5 in 1973, 9 in 1974, 6 in 1975, 4 in 1976, 6 in 1977 and 5 in 1978!!! Many of these had been written 10 or 20 years previously.

After his death, his newspaper articles were collected in several volumes. The title of one of these sums up Pedrolo’s spirit: “Cal protestar fins i tot quan no serveix de res – You have to protest even when it gets you nowhere.”