Berenice Abbot: female, poor and free

Man Ray got a fright when he realised just how good a photographer Berenice Abbot was, and he feared she might outshine him. He had hired her as an assistant when she settled in Paris in 1921 with no idea of how to take photographs. They had a lot of things in common: both were Americans of humble origins, unlike all the other artists, who generally hailed from old and wealthy families. The person Abbott actually connected with most, however, was another photographer she met when he was an old widower, Eugène Atget. He would go on to become the main stimulus for her major work: Changing New York.

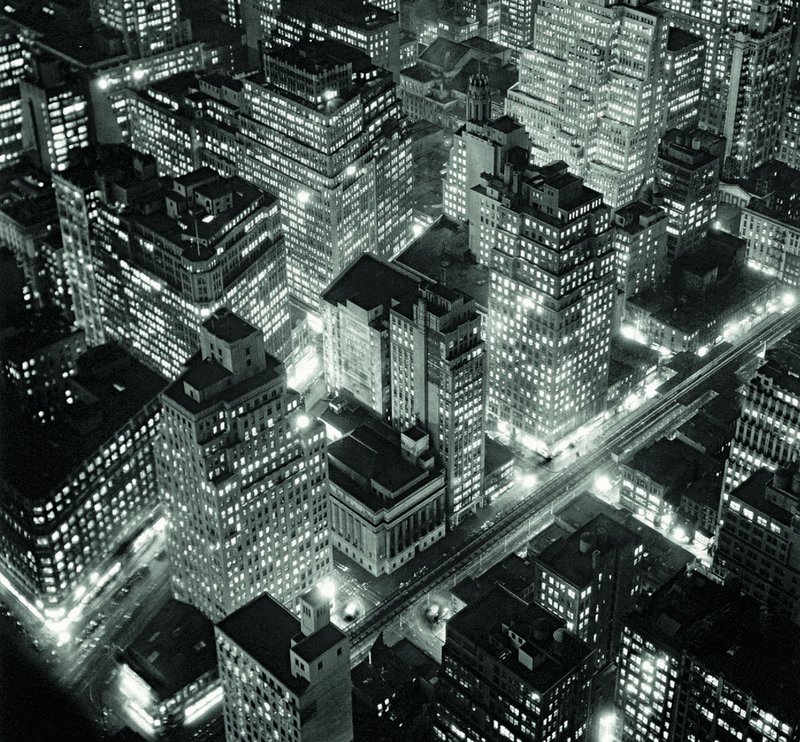

While Atget had begun work on a project aimed at preserving the essence of old Paris in the decade of the 1910s, when Abbott landed in a New York shaken by the 1929 crash, she saw its skyscrapers climbing high into the sky for the very first time. It was a city under construction, crying out for a new way of being understood and admired. And this is what she gave it. “Nobody would portray it with more skill and at the same time with more poetry than she did,” says Estrella de Diego, the curator of the exhibition Berenice Abbott. Retrats de la modernitat (Berenice Abbott. Portraits of modernity), now on at the Barcelona head office of the Mapfre Foundation. All the material on display has the added attraction of being vintage.

Abbott was born poor and died poor. However, she did manage to make a living from photography, and without needing to give up on her ideals. “Otherwise she wouldn’t have been able to do it”, says De Diego. Yet, she did not have the economic comforts afforded the likes of Marcel Duchamp, for example, whose circles she also moved freely in at the time.

Abbott was born in Ohio in 1898. At the age of 20, she moved to New York, initially with the dream of becoming a journalist, but then had to take any job she could, including debt collector.

She was poor and a woman: the worst combination. “She was a free woman who exercised this freedom,” says Nadia Arroyo, director of the Mapfre Foundation’s culture department. During the years that Changing New York was gestating, apart from looking for the most unusual views of the city (“she had to do some real stunts to get her photos,” says the curator), she also penetrated some of its darkest and most dangerous areas. “I’m not a decent girl,” she would say. “I’m a photographer and I go where I want.”

“With photography, which did not enjoy the status of art, she really could do what she wanted,” says De Diego. She herself “never wanted to be an artist; hers is viewed as documentary photography, but is it really?” the curator asks. It is a question that visitors to the exhibition can answer for themselves until May 19.