MEGACITIES of the future

With the world’s urban population set to keep rising, among the many challenges facing megacities is achieving sustainable and balanced growth. Catalonia’s largest urban centres are aiming to deal with their growing populations by opting to strengthen local neighbourhoods and empowering the citizens who live there

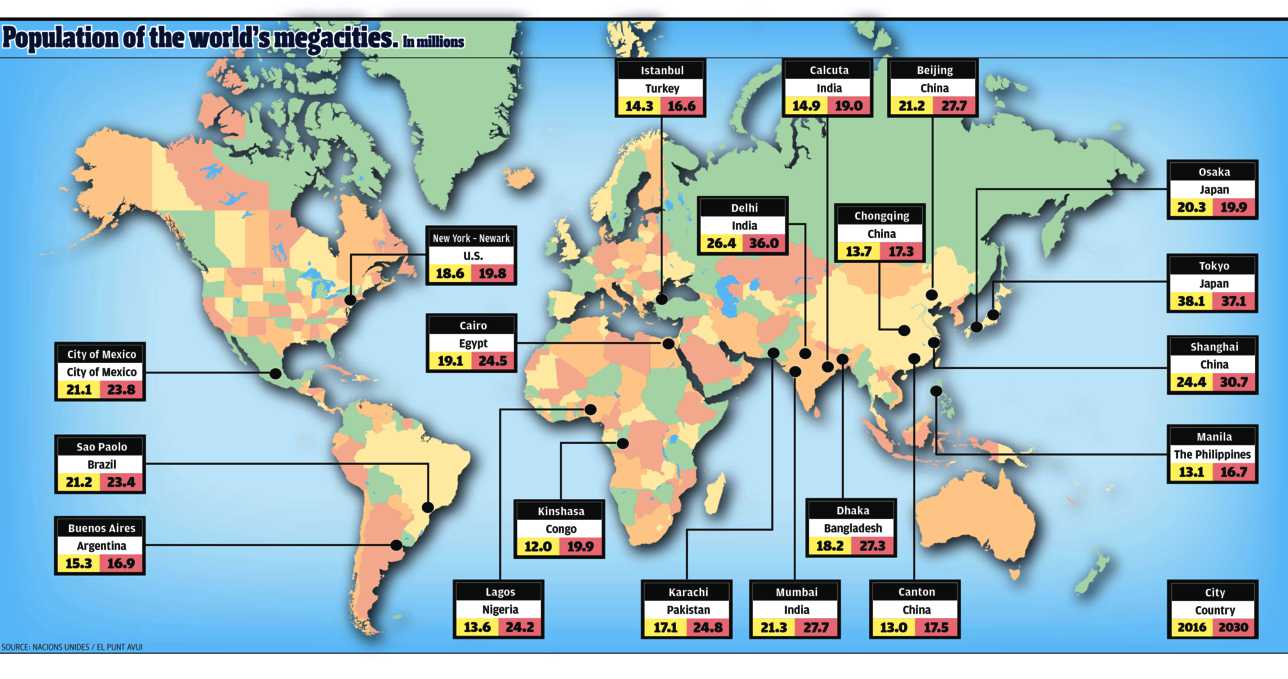

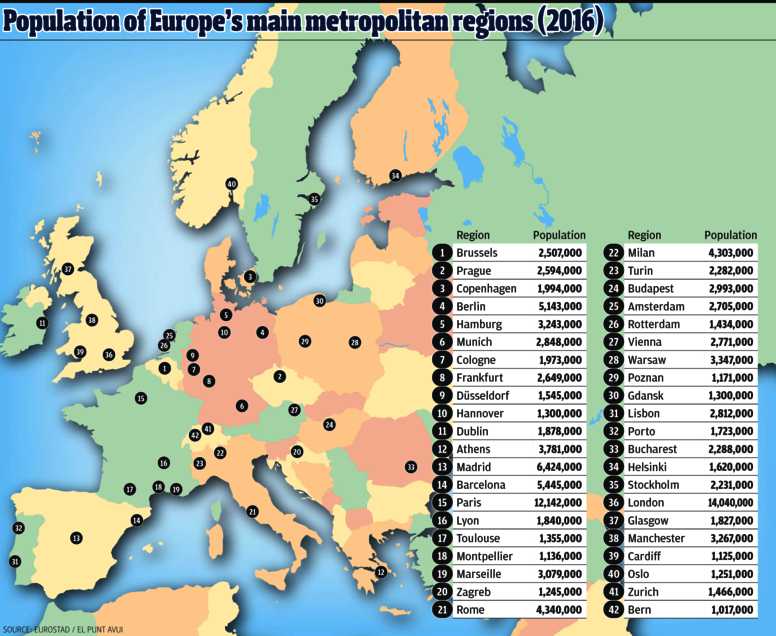

According to United Nations forecasts, the world’s urban population will rise from 54.5% to 60% by 2030. A good number of cities will reach 16 million inhabitants, and another group will have over 20 million, while others, fortunately the least numerous of the group, will have in the range of 30 to 40 million inhabitants. These figures will not be reached in Europe, however, and nor are they ever forecast to, with the exception of the exotic Istanbul, which has a foot in two continents and now numbers 20 million inhabitants. What is remarkable about Europe today is its large metropolitan regions. Preventing the large urban areas from overflowing requires careful management of resources, waste, mobility and governance, and planning balanced growth that takes into account citizens’ well-being, sustainability and the role of new technologies.

The 600 largest cities on the planet account for three-quarters of the world’s GDP and most are located in countries with emerging or developing economies. The question now is whether the power of these megacities will remain limited to their municipal scope. Some mayors around the world are already better known than the presidents or prime ministers of their countries, and experts are predicting that in the not too distant future the large-scale international summits, until now reserved for state representatives, will also include the municipal leaders of these big cities.

“Cities are facing two major challenges,” says Boyd Cohen, a professor at EADA Business School in Barcelona. “First of all, the application of new technologies to transform them into smart cities. Big data, the Internet of Things (IoT), transport efficiency and sustainable energy, among many other factors, will lead to the necessary creation of public-private management models. Secondly, people. These cities must be designed with them in mind and their voices will need to be taken into account.” Cohen recalls that diverse examples of governance already exist in Barcelona, “whereby citizens decide much more than just who will be the mayor every four years.” We are entering the era of citizen empowerment.

Civic entrepreneurs

The EADA professor gives as an example of this new citizen management the one implemented by Boston City Council, which “recruits civic entrepreneurs to present solutions to the various problems of the city, which has seen the creation of 51 shared mobility service entities.” As Cohen notes, “they are bottom-up and top-down models of city construction.”

Europe is pioneering experimentation in these new urban models, as the great concern at this time is how to balance the territory so that no area becomes a European megacity, with the problems that these large cities have with regard to sustainability and citizen well-being. The European Urban Agenda establishes guidelines for preventing rural depopulation and cities spiralling out of control.

“The concentration of people in cities is not desirable. They leave the countryside seeking education, work and services, and this is a global phenomenon. In Europe, this happens less because we have populations and cities that are widely distributed throughout the territory, but there are countries, such as Chile, where 70% of the population is concentrated in the capital,” explains Pilar Conesa, organiser of Smart City Expo World Congress and CEO of the consultancy firm Anteverti, which specialises in urban and digital transformation.

Large cities have advantages for the people who live there, but also pose serious challenges for those managing them, such as improving citizens’ quality of life, managing natural resources and the pollution caused by mobility. “This means cities are playing a growing political and social role,” says Conesa, who adds that “inequalities increase in megacities and we must therefore pay great attention to ensure social inclusion.”

In this regard, she points to the sustainable development goals developed by the United Nations, which sets out guidelines to address challenges such as poverty, gender equality, housing, sustainable energy and the growth of cities, among others. Europe also has its own roadmap to address the challenges of the future – known as Europe 2020 – and to prevent poor governance and anarchic growth in cities – the Urban Agenda – which establishes actions based on cooperation between regions aimed at achieving a balanced territorial distribution and sustainable urban development with a human focus.

Neighbourhoods are key

The problems associated with megacities can only be combatted, according to Conesa, “with more sustainable neighbourhoods and working to achieve social inclusion, not forgetting that the issue of gentrification must also be addressed, a problem that has been established in all the world’s cities.” The motto of the next Smart City Expo World Congress is “Cities to live in”, and it will be held in Barcelona from November 13 to 15 this year. “At the Congress we will tackle the balance between recovering neighbourhoods without expelling the people from them, and how this can affect the housing market through public action.”

Conesa explains that some experiences have been designed to curb gentrification have already been put into practice in other cities, “such as the project that was implemented in New York, where the people demanded smaller homes at more affordable prices in rehabilitated buildings located in very central places, so as to provoke a mix of social classes and nobody being expelled due to not being able to pay a high rental price. At the beginning, this decision led to confrontations with citizens of greater means, because they did not want to live next to people on lower incomes, but in the end it all calmed down. It’s an issue related to culture and change, a matter that the public sector has a big say in.”

Conesa believes that “if we want to have a sustainable city and quality of life for its inhabitants, we must work towards strengthening neighbourhoods. In Barcelona, this is very ingrained and we want each neighbourhood to have its own centre.” This is the strategy that Europe has also established to make cities inhabitable, because putting an end to megacities is an impossible task. “It’s a global phenomenon that will not stop,” says Conesa, “and we therefore have to turn them into places where people can live, and this requires taking care of the neighbourhoods, making very local policies and effective mobility policies, bearing in mind that to improve mobility, the first thing you have to do is reduce it.”

Building and strengthening the neighbourhood structure to not become an out-of-control megacity will also affect the labour model. “Right now, this is already changing, especially in northern Europe, where there are already companies that instead of having everything concentrated in a single work centre have chosen to set up in several buildings closer to their employees’ places of residence, be it on their own premises or in shared spaces,” explains Conesa. New technologies will benefit and promote these new labour models. In fact, the current boom in shared work spaces, or coworking, is a first step in the evolution towards this transformation of the world of work.

Younger generations of Europeans are already assimilating these cultural changes. They have adopted alternative mobility systems, such as the bicycle, and many choose to share a vehicle instead of buying one, “because in Europe cars are no longer synonymous with social status, as they are in North America and Latin America. Young Europeans are already growing up in a different social model,” comments Conesa.

Europe is like an island in a sea of megacities, where most have peripheries that are growing with no urban planning, infrastructure or services. “At Anteverti we’re working a lot with Mexico City and there are many neighbourhoods in the city that are practically rural areas, but immersed in a large city of over 20 million inhabitants. They do not have running water or lighting in the streets, or decent housing,” explains Conesa, “it’s a problem we also have to tackle all together.”

There are management challenges common to both megacities and large European urban areas. A dual vision is necessary: one for the large city and one that goes further and covers the whole metropolitan area, however large it is, because the physical limits between cities disappear and coordination and integration between different administrations become vital. In addition, Conesa says, “we must look for citizen cooperation, provide them with tools to participate in management and assume joint responsibility for actions carried out in their surrounding environment; that’s why it’s important to empower neighbourhoods.” She explains how the Colombian city of Medellín went from being known as the most unsafe in the world to being one of the most innovative, “and they did it by involving citizens in the transformation of the city, they made it feel like it was part of them.”

Industrial symbiosis

Other important actors in this urban transformation are industries, generators of waste and consumers of energy that must be recoverable. Sustainability and profitability are two concepts that embody industrial symbiosis. “It’s about creating an appropriate environment so that different types of companies can collaborate by exchanging all the resources they can’t manage,” explains Verónica Kuchinow, co-founder of the consultancy firm Símbiosy, which is responsible for creating a method for analysing information from a group of industries and creating opportunities to become more sustainable, without affecting the profitability of the business.

It is, according to Kuchinow, about “creating synergies and applying circular economy concepts to the productive fabric, which has serious problems with resources and is key to the change. Industrial symbiosis is the method for applying these concepts of circular economy.”

The aim of industrial symbiosis is to transfer the functioning of a natural ecosystem to the industrial fabric. “This is done by creating the right connections so that there is no waste, because all the energy is renewable, creating wealth through the diversity that is achieved in the territory,” explains Kuchinow. For her, the key words are “optimising and regenerating.” She says that prior to today, “an industry had to build a wastewater treatment plant, which also produces sludge as a waste, and that must be taken to a landfill. But if this company contacts another one that also has to remove the sludge waste from its wastewater treatment plant, and they are joined by two or maybe three or more, then surely there’s the opportunity to set up an installation and take advantage of the sludge to produce gas. And that gas can fuel urban buses in the nearest city. What was once waste has now become an asset.”

Industrial symbiosis is also a business, because if it were not it would not be possible to implement it. “It makes you realise that what for you is waste, for another company is a raw material and that the water that you don’t need may well be used by another industry,” says Kuchinow. Simbiosy works with the local authorities, “because they are the ones that have the citizens, the public facilities and the industries under their charge. It is the local authority that acts as an external facilitator with industries.” She also says that there is a lot of local government interest in industrial symbiosis projects because “they need the industries and must help them be sustainable.”

After participating in European circular economy projects, in 2014 the company implemented the first pilot industrial symbiosis project in Manresa, on the Bufalvent industrial estate, with the support of local businesspeople, the local town council and the Bages Waste Treatment Consortium. The project is being continued by the local businesses, as collaborative waste recovery brings profits.

The first step to starting an industrial symbiosis project is to carry out a thorough study of all the different businesses present on the industrial estate. “We take note of the waste they generate and other data, such as water use or energy consumption. When we have all the information, we cross-reference it and form groups of companies, making links between them and creating synergy maps. We then tell the local authority where work needs to be done,” explains Kuchinow. The company carries out the analysis and identifies opportunities before monitoring the project for at least a year, “until they can go it alone.” After completing the project in Manresa, they carried out others in Sabadell, Barberà del Vallès and Sant Quirze del Vallès. What’s most difficult is getting the companies involved,” Kuchinow points out, but little by little progress is being made.

Making a more sustainable world is a global issue. Natural resources are finite and a change of use and management models is essential. In Europe, we have a very different starting point to that of other parts of the world, which are immersed in the whirlwind of cities growing uncontrolledly. The roadmaps are on the table. Now is the time to apply them and make them work.

feature

feature

A large urban area in a small country

It may seem like science fiction, but there are few who do not accept that in two decades Catalonia could have one large urban region stretching along the coast in a line that would link three of the country’s four capitals and connect them with the region of Perpignan and Montpellier to the north of the Pyrenees. In order for this to become a reality, a series of infrastructure developments will have to be put in place that Catalonia has been demanding for years: the construction of the Mediterranean Corridor, the modernisation of the railway axes, for fast and sustainable mobility, the expansion of the airport facilities, and the deployment of a fast and direct connection between the airports of Barcelona, Girona and Reus. “The link between territories is increasingly important and the distance between Barcelona and Girona, for example, is ridiculous if you think that in many cities around the world it takes twice as long to go from home to work,” says Pilar Conesa, organiser of the Smart City Expo World Congress. The growth of large cities, both in Europe and around the world, is headed in this direction. The challenge is to build a territory that maintains a balance, and that depends on size.