Spirit of resistance

The contrast of such a heroic city so bowed in submission to the church surprises an American documentalist

Travellers in Catalan Lands

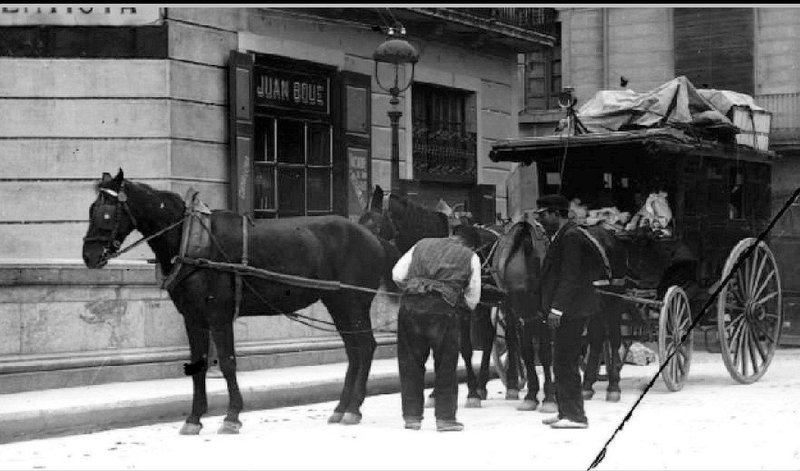

On the first of May, and a day, too, of balmy mildness which was worthy of the poetry that has been written about it, I came on […] to Gerona, where I dined. It has a long and famous history, was once a splendid city, as the remains of its earlier architecture prove, as well as the fact that it gave his title to the eldest son of the ancient kings of Aragon, who was called Prince of Gerona. Under Moors and Christians it has always been alike terrible in war and faithful in peace. Its most interesting point to me, however, is the awful resistance it made to the French in 1808, its final surrender, its generous rebellion in 1809, and the horrors of the siege that followed, when, after being blockaded eight months and remaining starved two more, it hardly yielded to three divisions of the French army. It is the first time I have been on a genuine field of Spanish heroism; and when I looked about me here, I saw the cathedral pierced with bombs and still bearing marks of having been fortified, and whole streets more or less marked by the desolation of war. I felt that I had come among a people whose genius and character is different from any I have seen yet, for, though I have been where much more blood was spilt, I have never yet found the traces of such a spirit of resistance as this.

Gerona, too, gave me my first glimpse of another less favourable side of the Spanish character; I mean its religious slavery. When I walked through the streets and found every fourth or fifth person I met a solemn ecclesiastic with a long black cloak and a portentous hat curled up at the sides in a most characteristic and exclusive manner; when I found the lower class of people doing more reverence to them than a Pharisee ever exacted, and all around me indicating the preponderance of ecclesiastical influence over every other, it seemed as if I must be in a dream […] When I was in Bologna, a city five times larger than Gerona, which contains hardly 12,000 inhabitants, I remember having been struck with the increase of the clergy, which was certainly natural enough on my entrance into a state exclusively ecclesiastical; but there is not so great a difference in this respect between Bologna and a Protestant town as there is between the most devout city in the patrimony of St. Peter and Gerona. I felt at once that I had never been in a Catholic country before.

In the evening I came on as far as Grenote [La Granota], a mere hamlet of four houses, such as we often see in America[…]I amused myself an hour, looking at them by moonlight and listening to the nightingales and whip-poor-wills with which the neighbouring woods seemed full, and whatever may be said in prose or in verse about the gaiety of Frenchmen, I do not believe all France could have furnished me such a sight as this. […]

“May 2. Still continuing my route through the fine country I have so long been enjoying and admiring, I came down upon the shore of the Mediterranean at Pineda, and passed along through a great number of active, industrious, thriving villages, where the men are fishermen and the women weavers and lace-makers, to Mataro, a town of 27,000 inhabitants. The cultivation was every-where neat and good, the population busy, well-nourished, and expert, and the country showing me plainly that it is improving and increasing, since everywhere I saw new houses building. Indeed, taking it all together, its delicious climate, sufficiently marked by hedges of aloes in all directions, and palm-groves, and its hearty, active, overflowing population, I do not know when I have seen a country that has pleased me more than this.

On the morning of the 3rd I passed through two or three more of the same kind of villages and great numbers of little hamlets. I finally entered the rich plain in which stands Barcelona. The plain, covered with country houses, bounded on one side by the Mediterranean and on the other by a long line of hills that follows the coast, and filled everywhere with the influences of the great city that closes up the prospect before you, a striking and majestic show.

George Ticknor

Pere GifraGeorge Ticknor (1791-1871), a true Boston patrician, was initially tutored at home by his parents, and then attended classes at Dartmouth College, where he graduated and eventually pursued legal studies. His linguistic and literary leanings pushed him into the world of letters. He spent a long sojourn in Europe (1815-1819) where he studied and travelled meeting eminent politicians, writers and scholars, establishing long-lasting personal and professional networks. Back in the US, he was appointed professor of modern languages and literature at Harvard. He then began a second tour of Europe. The books and manuscripts he collected for years became particularly advantageous for him to write the three-volume History of Spanish Literature (1849), a widely acclaimed work that –along with his modern teaching methods– won him the unofficial title of “father” of American Hispanism. Ticknor travelled to Europe once again to acquire more documents for Harvard and upon his death bequeathed it thousands of invaluable volumes. Even though during his lifetime he never wrote a fully-fledged travel book, his journals and letters, published posthumously, provide ample evidence of his wide interests and enlightened pursuits. Crossing Catalonia during the spring of 1818, he did not hesitate to denounce the religious slavery of such a place as “heroic” Girona, at the same time as he praised the industriousness of the thriving towns in the Maresme area.