Marooned in a small grey country

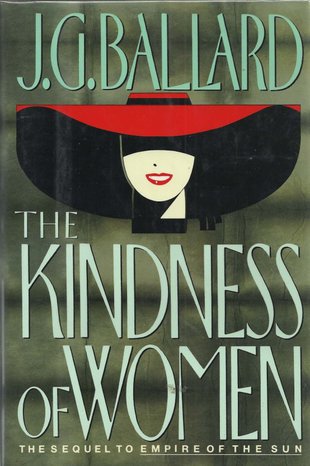

The Kindness of Women is an autobiographical fiction based on James G. Ballard's life from when, still a child, he was interned in Lunghua camp in Shanghai, by the Japanese during World War II, through to the 1980s when he finally writes his novel Empire of the Sun about that inferno that Steven Spielberg turned into a film in 1987

While Empire of the Sun was, despite war, hunger and the prison camp, upbeat and optimistic – there was always a better future awaiting –, The Kindness of Women is a darker novel. It starts once more in Shanghai, but here Jim the narrator watches in fascination bodies being blown apart as the city is bombed and the torture and killing of a Chinese youth by four Japanese soldiers. In the camp where foreign nationals are interned, Jim lives through the breakdown of British colonial society as confidence in their imperial power suddenly collapses.

When Jim reaches England in 1946, “I was marooned in a small, grey country… a labyrinth of caste and class.” He has been exiled from England by Lunghua. He has witnessed murder and learnt that the narrow patina of conventional life cracks too easily. Unable to fit in, he runs through a variety of jobs. He studies medicine to see if dissecting cadavers might exorcise his memories. He joins the Air Force, preparing for World War III.

Then he meets Miriam and they have three children, two girls and a boy. Secluded in their suburban house by the Thames, Jim lives an “endless summer” of intimacy he had thought impossible. It is the childhood he had lost in Shanghai.

The World's End

Yet summer ended in a blink of God's eye. Miriam dies in a holiday accident on the Costa Brava. The rest of the novel charts Jim's 'crazy years' in the 1960s with his bizarre friends and his pleasure in bringing up his children. How can you manage? concerned well-wishers ask. He realises his children are bringing him up. The kindness of women? It is not so much that they are kind, but that all his male friends are crazy, as Jim is himself. Only the women, though many of them are mad too, save him.

There are just 20 pages set in Catalonia in this book, but they are central, as they describe the disaster of Miriam's death. If anyone should be enticed into thinking that The Kindness of Women is a literal account of Ballard's life, resist the thought. It is a hybrid of autobiography and novel, in which Ballard shuffles the events of his life to try to make sense of his times. In fact, Ballard's wife had another name, did die young, but did not die in an accident in Catalonia.

On the Bay of Roses, Jim and his family are in paradise just before the Fall. “Untouched by the feet of holiday-makers, the white sand was like fluffed sugar”. But already plots by the beach are being marked out for building “villas for Dusseldorf dentists” and Miriam is about to slip, crack her head and die. As the traumatised Jim and the three children drive away after her funeral, he reflects that: “The resort beaches of the Costa Brava, the hotels and cafés slid past through a dream more lurid than any of Dalí's paintings, a vision of the world's end seen in terms of polluted sand, the stench of sun-oil and terraces of over-exposed flesh.” This is Ballard's vision: apocalyptic, overblown maybe, but bold and trying to make his readers think.

Wild yearnings

Criticisms of The Kindness of Women focus on two types of explicitness. Jim's sexual life is chronicled in clinical detail. This underlines the dislocation between sex and feeling in him. Chilling scenes of prostitution at a Rio film festival show both Jim's callousness and his very precise eye. The sexual explicitness also leads to welcome uninhibited descriptions and to a moving account of childbirth.

The other kind of explicitness is when Ballard spells out his themes too clearly, instead of letting them speak for themselves. For instance, the association between his watching the Chinese youth being strangled slowly by a telephone cable and his fascination with corpses and car accidents are repeatedly brought out in sentences that sound pretentious. “Had the events in Dealey Plaza [where President Kennedy was shot] been no more than the most elaborate of a series of strange accidents prefigured on that Shanghai race-course of my childhood?” Yet, in Ballard's defence, if you do not risk pretension when struggling to express what is hard to express, you may censor yourself to simplicity and will never attain originality.

The Kindness of Women shows, too, the social revolution of the 1960s. As Britain's colonial order has broken down, a newer society is being born: one that is damaging and crazy, like Jim's friend Sally's needle-pitted arms; and at the same time, one that is more caring, open and imaginative. Ballard digs into the contradictions. Sally herself, so wild and self-destructive, is endlessly kind to Jim's children.

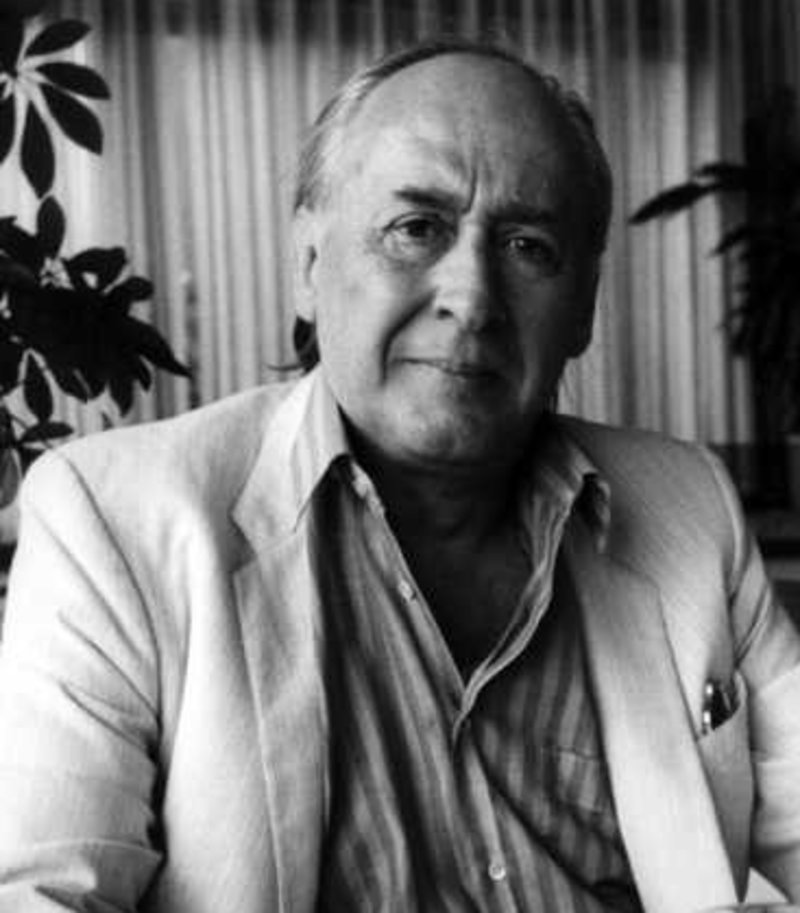

Ballard is one of the most original writers of his generation. Like Salvador Dalí, who draws figures in pin-pointed detail beside monstrous images dragged from his unconscious, Ballard uncovers in hypnotically calm prose the wildest yearnings of our secret selves. His voice is matter-of-fact, while the content is extravagantly surreal.

Secret desires

James G. Ballard (1930-2009) was known as a science fiction writer from his short stories of the 1950s and his first novel, The Drowned World (1962). His was not the science fiction of monsters from outer space, but rather reflections on a world recognisably our own, but beset by ecological, political and psychological disaster. He worked on a science magazine in the 1950s and science informed both his imagination and sober, straightforward style. So sensible-sounding it verges on the mad. His Crash (1973), later filmed by David Cronenberg in 1996 and starring James Spader and Rosanna Arquette, explored Western society's obsession with fast driving, social acceptance of random death on the road and sexual attraction to car crashes.

It was not until the autobiographical Empire of the Sun (1984) about his adolescence in a Japanese prison camp in Shanghai that he became recognised as one of Britain's major novelists. The Kindness of Women, reviewed here, was the sequel to Empire of the Sun.

Ballard's terrifying Cocaine Nights (1996) and Super-Cannes (2001) were novels about only-slightly futuristic enclosed communities in which too much leisure led to murder. Set in Mediterranean Spain and France, respectively, these two books built on both the evocation of the British on holiday and the breakdown in civilised behaviour in stressful situations that he had explored in The Kindness of Women.

By my count, Ballard published 19 novels and 16 volumes of short stories. He lived in Shepperton from 1960 to the end of his life and it became a perennial theme of articles and interviews during the fame of his last 25 years that he was the surrealist writer of apocalypse and dystopia living in a peaceful, suburban house in a boring outer suburb of London. Making places like sleepy Shepperton feel dangerous was his gift: his scary imagination uncovered unspoken desires behind conventional housefronts.