The city of water and stone where I was born

In the most intense five days of her life to that point, as Catalonia's revolution of July 1936 explodes, a 22-year-old Helen changes from being a visiting journalist to become a committed radical

Helen changes too from a young woman unsure of herself to an adult understanding her place in the world. In the Barcelona turned upside down in the first days of Revolution, Helen finds “the end of confusion.” It is no paradox. Though Revolution is chaos, a new order is being built by the dispossessed. “I began to say what I believed”, Helen thinks.

General Strike

Helen has been sent to report on the anti-fascist alternative to Hitler's Berlin Olympics, the People's Olympiad due to start in Barcelona on July 19, 1936. The train from Paris carries a mixed bag of passengers: the Hungarian, US and French teams to the Games, tourists, three Hollywood producers, local women.

The train halts in Moncada station (today, Montcada i Reixac), 10 miles short of Barcelona. A General Strike has been declared against Franco's military rebellion. The passengers react in varying ways to the news filtering through. Helen makes friends with two Communists, a black woman, Olive, and her white husband, New Yorkers like her. She meets a German runner, Hans, and they have sex in an empty train compartment. The Olympic teams go into the town and, despite the language barriers, show their solidarity with the town on strike. Five fascists are killed. Religious pictures and icons are brought out of houses and burnt, but there is no looting. There is shooting in the hills. Despite the braggadocio of the Hollywood producers that they'll fix this stupid fuss, it becomes clear that a full-scale Revolution is taking place.

The second half of the novel takes place in Barcelona, where the passengers have been taken in a pick-up truck. There are still snipers around. One of the French Olympic team is killed. In a swirling kaleidoscope of faces glimpsed and lost in the crowd and people rushing about, meals and accommodation are improvised. Self-organisation is imposing its order.

This is an autobiographical novel. Throughout, Rukeyser is keen to pinpoint detail, which makes it a fascinating first-hand source for historians. There are not so many accounts of these days written immediately afterwards, while memory is fresh and undistorted. Women are Rukeyser's main speakers. At the beginning, three local women on the train are discussing politics. Helen can't understand their Catalan, but she catches “anarquista”, “comunista”. Helen is listening all the time, learning. She feels something new. Rukeyser is explaining how Helen and others are changing under the impact of massive events.

For the rest of her life Rukeyser would repeat that Barcelona was “the city of water and stone where I was born,” even though she had only been in Catalonia for five days.

Gross rejection

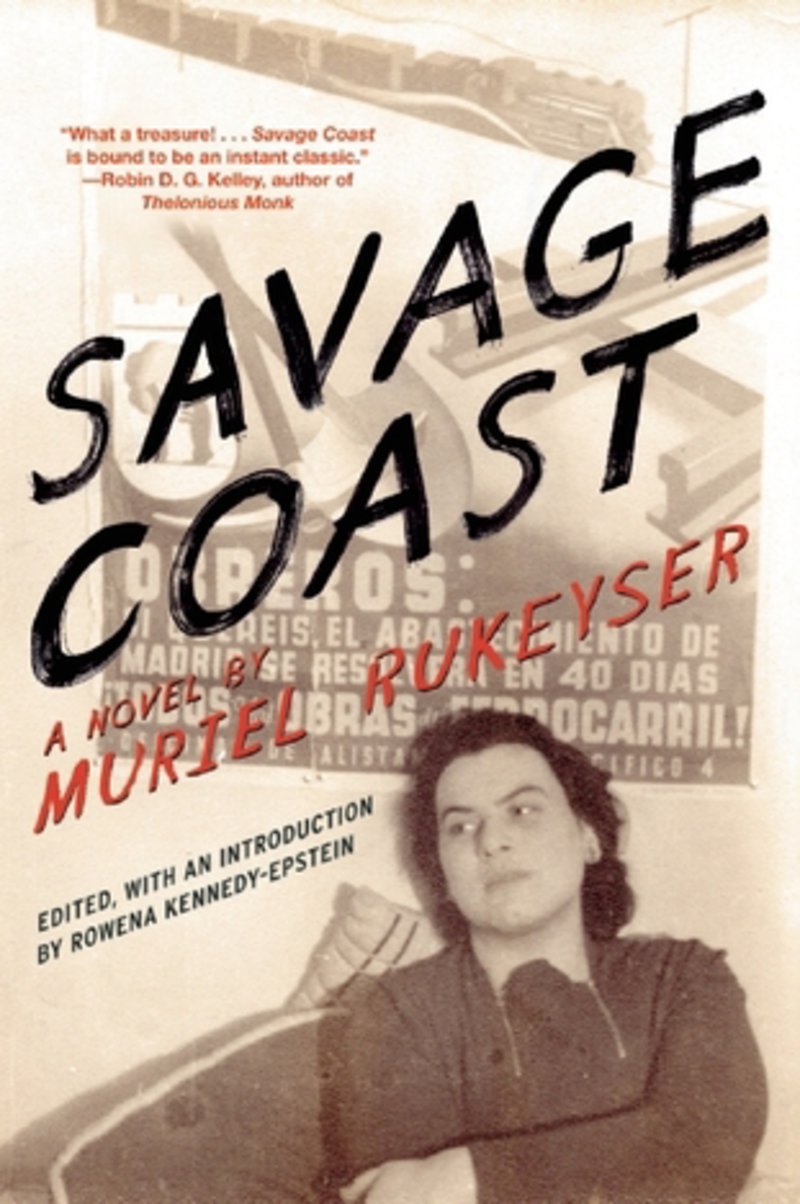

Savage Coast (Rukeyser's translation of Costa Brava) has an extraordinary publishing history. In Autumn 1936, Rukeyser sent it to a publisher who replied with a brutal letter of rejection: “one of the worst stretches of narrative I have ever read,” with a heroine “made to seem too abnormal for us to respect what she sees, hears and feels.” BAD, he wrote in capital letters.

There is evidence that Rukeyser re-worked the novel until at least the end of the Civil War. Some of the middle chapters are incomplete, though they are quite readable. Later she mined it for poems and articles (one of which, from 1974, is included in this volume). Never published in her lifetime, Savage Coast was discovered among Rukeyser's papers in 2011 by Rowena Kennedy-Epstein, a research student and now the novel's excellent editor.

The novel is not perfect. Helen's lover Hans is an idealised vision of handsome, heroic male strength. With Hitler in power making him homeless, he will stay to fight: “Spain is my country now.” Rukeyser repeatedly calls two American women a jarring, “the bitches”, for no explained reason. If you are out of sympathy with Helen's personal journey from confusion to commitment, you may find the book irritating, but it is not BAD.

The original rejection was so curiously gross and intimately hurtful a response to a book that the novel must have deeply offended the publisher.

But where could the offence lie? In its content and its form, both experimental.

Kennedy-Epstein believes that Rukeyser's young, sexually free and free-thinking heroine was just too much for the publisher. She was ahead of her time. The content is feminism and revolution. And the form is fractured and modernist. Rukeyser includes extracts from novels, documents (such as the fascinating manifesto of the People's Olympiad) and poetry as well as prose. What John dos Passos did in his huge 1930s novel U.S.A. was not allowed to a young woman. Kennedy-Epstein summarises that Rukeyser was discouraged from “writing the kind of large-scale, developmental, hybrid, modernist war narrative that she had begun – one that is sexually explicit, symbolically complex, politically radical, and aesthetically experimental.”

In the moving climax to the novel, Helen stands alone in the middle of a huge, heavily armed crowd shouting in languages she cannot understand – and she feels safe and free. She is at home in the revolution.

Rukeyser's responsibility

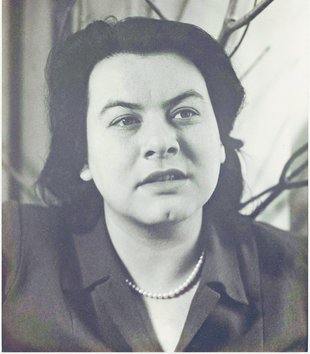

Muriel Rukeyser was born in New York in 1913 to non-observant Jewish parents and died of a stroke in 1980, aged 66. She was a well-known poet in her lifetime and even more so after her death, as feminists recovered and discovered her. She published over a dozen books of poetry. Her first, Theory of Flight, won the Yale Younger Poets Prize in 1935. She found her voice in her second, The Book of the Dead (1938), a group of poems polemicising against silicosis among miners.

Rukeyser believed that poetry was essential, “infinitely precious” as she wrote in The Life of Poetry (1949). Rage at oppression combined in her writing with optimism that equality and social justice could be achieved. She was often compared with Walt Whitman for her powerful voice and rebellion.

If poetry was her great passion, the other was political activism. She was jailed twice in her life, first for “associating with black men” when in 1932 as a college journalist from Vassar she covered the frame-up for rape of nine black teenagers, known as the Scottsboro Boys; and then in the late 60s for protesting the Vietnam war. In the 1960s and '70s Rukeyser, as President of PEN's US centre, led international campaigns to defend dissident writers.

It was Rukeyser's fate to suffer criticism for sticking political views in poems. The objections boil down to opposition to her political and artistic struggles. Women were meant to write fine lyrics and domestic dramas, not “mighty lines” to protest capitalist slaughter.

In many of Rukeyser's articles and poems on the Spanish Civil War, composed across 40 years, she returns to the moment when she is given her “responsibility” by the organiser of the People's Olympiad, who tells her and the other foreigners about to be evacuated: “It is your work now to go back, to tell your countries what you have seen in Spain.” Rukeyser fulfilled this commission to write and fight for justice all her life.