Long-term resident

Belarus and Ukraine today

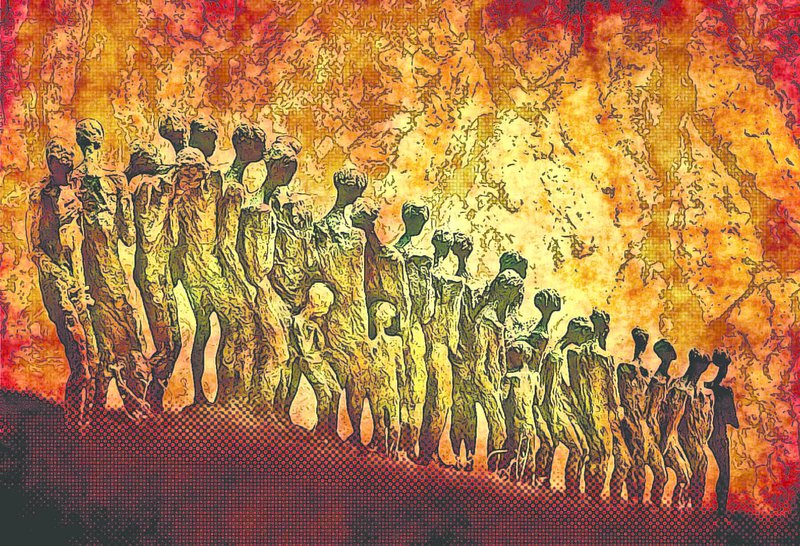

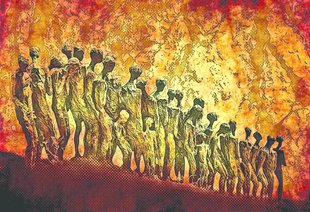

It would have been natural, given that I've just travelled to these two relatively unvisited countries, to write a travel piece about them. About the safe streets of Minsk, for instance (the poshest of which is named after Karl Marx) where the statue of Felix Dzerzhinsky (founder of the Cheka) rubs shoulders with Apple outlets and luxury jewellers'; or about the deliciousness of kvas (a soft drink made from bread). And in Kiev I could have gone on (and on) about the beauty of its buildings, the stunningness of the views over the Dnieper, and the glory of its vereniki (sumptuously stuffed dumplings). Etcetera. But highly appreciable though all these things (and many others) are, I went to the aforementioned countries for another reason: to see some of the places I've been reading about for the last 40 years due to an abiding interest in genocide in general and the Shoah in particular. Places like The Pit in Minsk, in which 5000 Jews - including 200 orphans - were shot in one day in March of 1942 (the monument there shows a huddled, terrified crowd clambering down the slope that leads to the killing site). In the course of World War II, Belarus lost a quarter of its population (including the near entirety of its Jewish component), and monuments to this loss are everywhere to be seen. As for Ukraine, its first mass atrocity took place courtesy of Stalin, who, in 1931, launched a policy of grain confiscation to supply the larger Soviet cities, which resulted in the Holodomor: a famine in which between 3 and 5 million Ukrainians died of starvation in one year. Later, in WWII, hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian Jews were shot into mass graves, including nearly 34,000 of them in just two days in September 1941, in the Babi Yar ravine (now part of a park in northern Kyiv: kids sled down the slopes). Forward looking though Belarus's and Ukraine's populations are, they are both unable and unwilling to forget the horrors of the past. (In Ukraine, what's more, the horror hasn't stopped: Tatars in occupied Crimea are regularly kidnapped by Russian-backed security forces and 'disappeared', and the war in the east - in which 9000 people have died - is still ongoing). According to historian Timothy Snyder, the scope of the WWII atrocities in Belarus and Ukraine was made possible by the fact that for years everyone (except the people who lived there) did not regard them as serious political entities, obliged as they had been in the past to form parts of larger states, which meant they emerged only fleetingly on what is so pompously called the stage of history. In other words, they were considered fair game by those playing the latest version of the Great Game. As has, indeed, been the case with Catalonia; although, by comparison, Catalonia would appear to have got off fairly lightly.