Echoes of modernity

A book reflects on the influence of Hollywood movies in the lifestyle and in the change of attitudes of women in the twenties and thirties

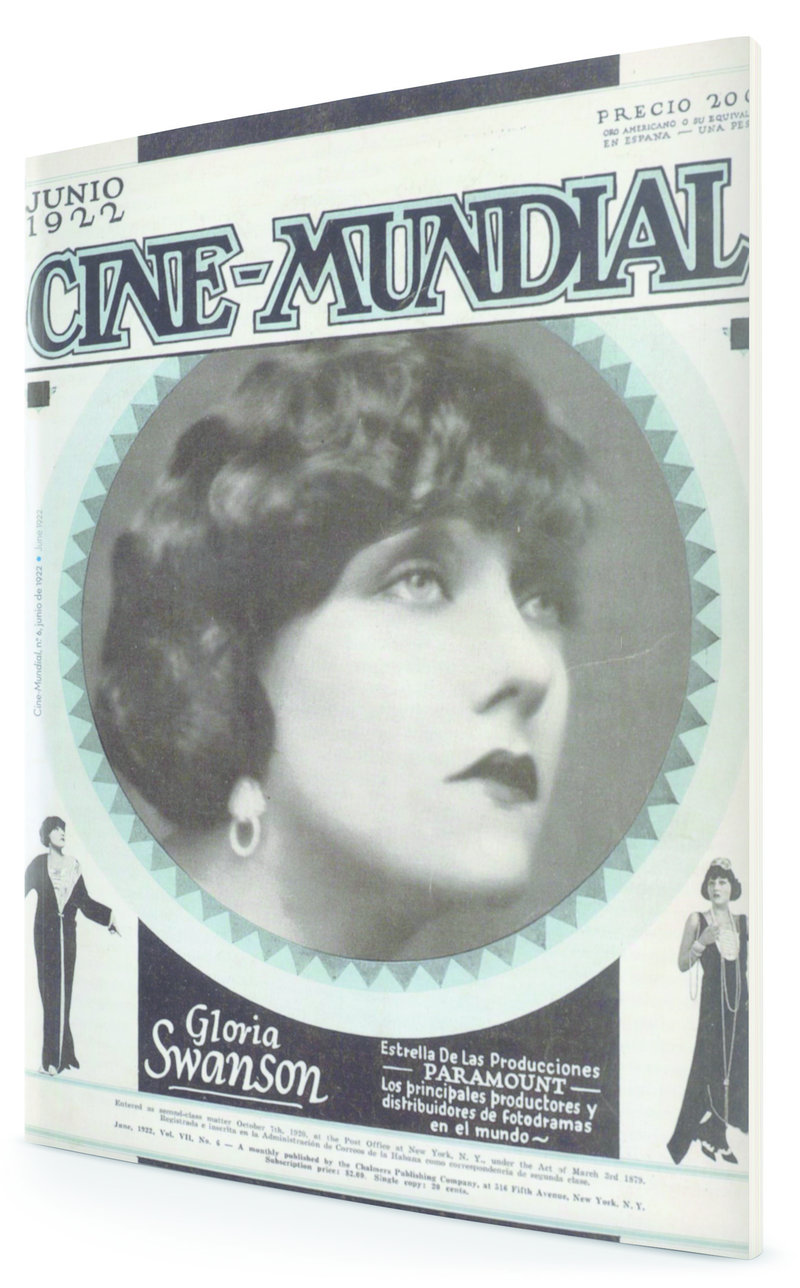

In an article in the June 6 1922 issue of the magazine Cine-Mundial titled “Presentando a la flapper”, the author, Josefina Romero, defined her as a “capricious creature” with “short and extremely curly hair.” It is the female model American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald described so well in his stories about the twenties, most probably inspired by his wife Zelda. The writer Vicenç Pagès Jordà, in an article about Vicenç Coma (1893-1979), in describing the same atmosphere as Scott Fitzgerald, said that flappers “drink Pommery champagne, dance the shimmy and the foxtrot and enjoy intense and ephemeral relationships “; in addition to the aesthetics, Pagès Jordà highlights the flappers as “representing the first liberated women.”

Flappers were the icons of these “echoes of modernity”, represented in films such as It (1927, released as Ello in Spain), starring Clara Bow, and that somehow served as a mirror for the Spanish woman in the 1930s, even though half the female population could neither read nor write. But in the thirties, the Second Republic (1931-1936) brought about political and social developments that would contribute to a changes in relations between men and women, epitomised by the right to vote (1933 ) and the first divorce law (1932). In the cultural sphere, women became more visible, with platforms such as the Lyceum Club (1926). However, these advances would come to an abrupt end following the Civil War and especially during the darkness that spread over forty years of the Franco dictatorship.

The discovery of an old box filled with close-ups of actresses collected over the years by José Romero Sampedro, a regular of the Granada's Coliseo Olympia cinema (where his cousin was projectionist) is almost something out of Cinema Paradiso (1988). It has served as an excuse to gather these photographs of Hollywood actresses, along with newspaper clippings of the time, and publish them in a luxuriously presented book, in both Spanish and English. Published by the Agencia Española de Cooperación, the book was edited by Eugenio Fontaneda Berthet, who in his prologue thanked Romero Sampedro's son for handing over the legacy of his father, which made the project possible. The aim of Mujeres de cine. Ecos de Hollywood en España. 1914-1936, explains Fontaneda, is to present the women in the historical perspective of those “turbulent years”, but also to reflect on the impact that film, and especially the image projected by actresses in the roles of “daring” and “ liberated” women had on the viewer. More than a mere perception of the characters, the cinema was also “ a promoter of development and change of the role of women in Spain during the first third of the twentieth century.” To this end, texts by journalists, historians and experts in illustration accompany the photographs gathered by the collector from Granada.

The filmmaker Isabel Coixet also “happily” contributed a prologue which emphasizes that the book “has the ability to equally seduce lovers of history and lovers of the cinema.” Coixet says that “through the different approaches” taken, “the reader can understand the role of the star system, how it influenced the change of habits of women of the time, and showed cultural currents which dominated over two decades.” Coixet continues: “Somewhere between the fiction Hollywood proposed and the reality that they lived, women were able to conquer small elements of freedom that often had their glory in the eighty minutes that a film took.” The director also emphasised that the book includes “an incisive analysis of films that, for various reasons, had been forgotten, which gives us a glimpse of Hollywood before the Hays Code far less sweet and rosy than we might suppose. “ The Hays Code, in force from 1934 to 1967, is the self-censorship that prevailed in studios, dictating what could be seen on the screen as morally acceptable.

TVE journalist and film buff Moses Rodríguez in one of the texts, recalls that the first woman who appeared in a silent film is the dancer Carmen Dauset. Artistically known as Carmencita, in March 1894 she visited the first film studio of an incipient industry, New Jersey's Black Maria Studio, to perform a dance routine. Thomas Edison filmed the scene, which although only lasting 21 seconds, was used to promote the “kinetoscope”, the forerunner of the modern projector. Rodríguez uses the anecdote to relate the impact of the American cinema on women and in Spanish society in general: “The cinema was very cheap and not all that popular [...] right up until the thirties the theater was still the main source of entertainment and means of propaganda used by trade union and political movements around the country.“ The journalist adds that “at the end of the Primo de Rivera dictatorship (1923-1930), the audience was still not well versed in the cinema.” Films were advertised a week in advance so that the public, mostly women in cities and in some villages, would book tickets, and the programmes advertising the films featured young women dressed in Manila shawls to attract viewers.

The period covered by the book coincides with the most ostentatious display of feminine aesthetics and for this reason advertising for films starring the likes of Gloria Swanson or Joan Crawford put more emphasis on the glamorous clothing and adornment of the actresses rather than the argument of the film. This was the key factor in the popularity of film magazines of the time. In some Spanish newspapers such as La Libertad in 1932, there are sections titled (in English) “Talking Pictures” with aspiring movie stars and photogenic actresses talking about their dreams along with gossip about their love lives. It was an informal style aimed at involving the readers; a reflection of the impact that the star system began to have on the country. But beyond aesthetics and the images, just what influence did the roles the actresses played in the most popular movies have?

The truth be said, the prototypes were even revolutionary for republican Spain: sexually aggressive, as Mae West in I'm No Angel (1933) and Jean Harlow in The redhead (1932). Others were more progressive, yet without flaunting themselves but neither ashamed of themselves, like Norma Shearer in The Divorcee (1930) and A free soul (1931), a very significant title. This model wife was more “human and realistic” seeking a change in their role in society and in relationships with men, with a greater impact “on urban and educated classes.”

The Hays Code was a major setback. It was introduced in 1934, but in the four years beforehand there was a series of films in which the prototypes of the traditional female character developed into a modern heroine, who managed her life freely, ignoring the prevailing male-centred rules. Writer Guillermo Balmori emphasises that the book shows “the truly liberating effect for women” of film in the pre-code period. Women are decision makers, they break taboos, and take control of their destiny without paying a price.”

'Vamps' and 'flappers'

Hollywood projects female stereotypes. There is the wicked woman, the misogynistic vamp, a term that implies that the woman has a vampiric effect on the male, a direct antecedent of the “femme fatale”. In contrast, is the traditional heroine, the wife in the films of DW Griffith, the Mary Pickford styled “American girlfriend.” And there is the flapper seen here as actress Clara Bow, representing women as an “independent hedonist and lover of jazz.”