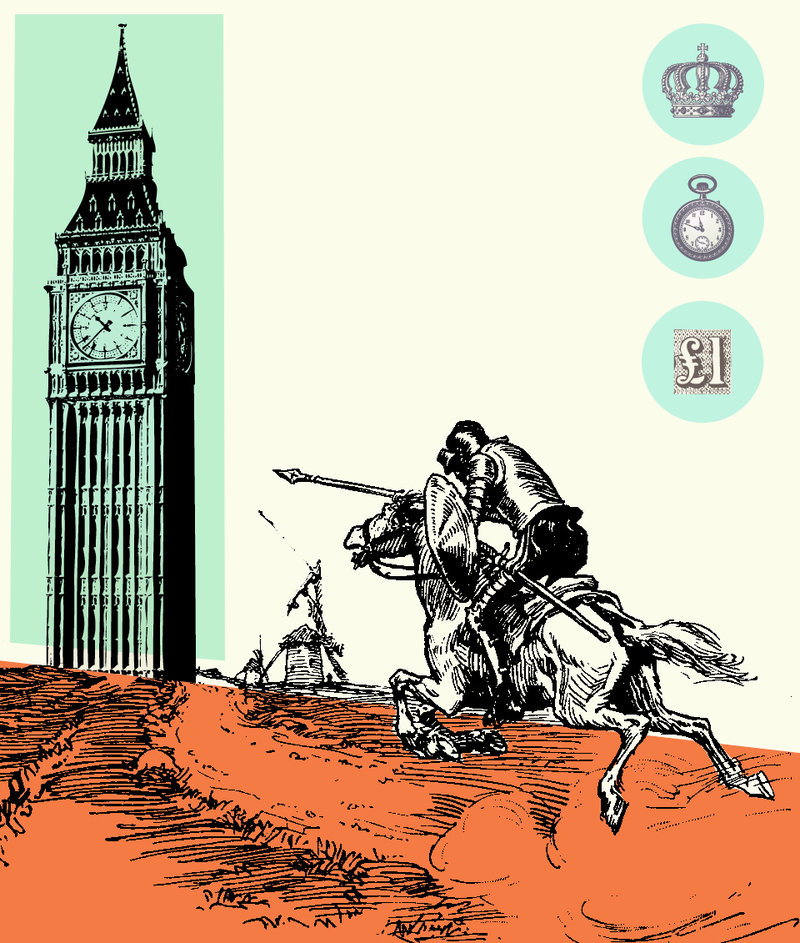

The English Don Quixote

On the 400th anniversary of Cervantes' death, professor Bartolomé analyses his influence on Anglo-Saxon authors

This spring we commemorated four centuries since the deaths of two of the great geniuses of world literature: Cervantes and Shakespeare. If Alexandre Dumas was right when he said: “After God, Shakespeare has created most”, then the Spanish author would come third in the ranking of Anglo-Saxon literary influence (first place would presumably be taken by the King James Bible).

Whatever the case, the Cervantes collection in the British Museum is certainly testimony to the enormous stamp that Don Quixote has left on English literature. The first part of Don Quixote was translated in 1612 and quickly served as inspiration for the lost play Cardenio, performed in 1613, and penned by Shakespeare and John Fletcher, who knew Spanish. Cervantes' great book became rooted in 17th century English literature with constant allusions to the hero and his adventures in the work of some of the era's most important playwrights, such as Ben Johnson, Francis Beaumont and Fletcher. It continued to exert an influence throughout the post civil war period, influencing such works as Samuel Butler's satirical poem Hudibras, with its parody of errant knights, or the theatre piece, the Comical History of Don Quixote, by Thomas Urfey, for which Henry Purcell composed the music for some of its songs.

Various translations continued to keep the interest in Cervantes' work alive until the boom of the novel in the 18th century. In fact, the development of the English novel owes a great deal to Cervantes, as the interpretations of Don Quixote began to see him as something of an Everyman. In the words of Peter Motteaux, whose translation first appeared in 1700, “everyone has something of Don Quixote in his humour, some beloved Dulcinea in his thoughts, which make him go on adventures.”

Meanwhile, the critic Lionel Trilling (The Liberal Imagination) stated, “All prose fiction is a variation on the theme of Don Quixote,” and indeed many English writers of that century would draw on the figure of Don Quixote, from Henry Fielding (Joseph Andrews), Samuel Richards (Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded), Richard Steel and Joseph Addison to Jonathan Swift (A Tale of a Tub), Laurence Sterne (Tristam Shandy) and Tobias Smollett (Humphrey Clinker).

Into modern times

In the 19th century, echoes of Quixote can be traced in the novels The Newcomers by W.M. Thackeray and especially in Charles Dickens' The Pickwick Papers. In this, Dickens' first work of fiction, the Quixote-Panza duo is represented by Don (Samuel) Pickwick and his servant Sancho (Sam) Weller. In fact, the Pickwick Papers has even became known as “the Quixote of the English novel.”

Meanwhile, scholars have also found parallels between the realist structure of Quixote's adventures and those of the archetypal heroes of American novelist Mark Twain (Tom Sawyer, Huckleberry Finn). In both of Twain's works there is Cervantesque symbolism in the journey's the heroes of the books make around rural Missouri and along the Mississippi river, in their adventures, humour and language. Also, the western literary genre of the solitary cowboy and sidekick (developed in the 20th century) harks back to Quixote, such as the classic Shane (1949) by Jack Schaeffer and even the graphic adventures of Lucky Luke.

Cervantes' infiltration of popular culture was led by the growing cinema industry in the US and even finds its way into cartoons, such as Hanna-Barbera's Don Coyote and Sancho Panda, but in the 20th century the literary connection continues. Travels with Charley in Search of America (1961) relates John Steinbeck's adventures travelling America as a 60-year-old, accompanied by his dog Charley, in the van he named Rocinante. Graham Greene also called the Seat 600 Rocinante that appears in his pastiche of Cervantes' work in his novel Monsignor Quixote (1982). This fun book provides a fable of our times, following the travels of a Catholic priest in the company of the Communist former mayor of El Toboso (naturally nicknamed “Sancho”) in post-Franco Spain.

Another example of Cervantes' influence on 20th century literature is the fictional character Ignatius J. Reilly in the Pulitzer-winning novel, A Confederacy of Dunces (1980), by John Kennedy Toole, which was published after his suicide. The book's main character is eccentric and idealistic, driven to a point at which he loses his grip on reality. In his foreword to the book, Walker Percy describes Ignatius as a “slob extraordinary, a mad Oliver Hardy, a fat Don Quixote, a perverse Thomas Aquinas rolled into one.”

Quixote today

Meanwhile, one of the icons of contemporary English literature, author Paul Auster, has openly recognised Quixote as “the novel of novels” and the one that has had the biggest influence on him. In the first part of his New York Trilogy (City of Glass, 1985), there are numerous allusions to Cervantes in this brilliant variation on the classic detective novel.

New translations published in the 20th and 21st centuries have since updated Cervantes for new generations of English readers, including the Spanglish version by Ilan Stavans in 2003 (“In un placete de la Mancha of which nombre no quiero remembrearme, vivía, not so long ago, uno de esos gentlemen,” and so on). Cervantes may have died four centuries ago, but it his literary legacy is still very much alive in Anglo-Saxon literature.