Avoiding the Sagrada Família

Every year, thousands of young men and women flock to Barcelona just because it's a cool place to live. What destiny awaits them in this city of legend? They usually end up teaching English, though they may never have faced a classroom in their lives.

Ferry, though he's called too often for his liking Ferret, flees his dead-end job (short-order cook) and family in San Diego, California. More than anything, 27 year-old Lester Ferry wants to get over his affair with Svetlana, who was so “voluptuous” and “sensual” that he knew from the start she was going to dump him.

It's 1998 and he picks Barcelona off a map. He's heard of the Olympics and it's near Italy, where Svetlana had dreamt of living with a previous boy-friend. He wants a real job: he imagines himself working on the docks (but they're unionised), as a neighbourhood grocer (but he's got no papers) or as a taxi-driver (“They're the Mafia,” someone remarks). There's nothing wrong with Ferry's imagination, but what can he do to pay for the converted closet where he sleeps in Paz's flat and to keep him in calamari and alcohol? He teaches English.

Let us be clear: there are excellent teachers of English as a Foreign Language, trained professionals with qualifications who prepare their classes and give value for money. This is not a novel about them.

The innocent abroad

I have been green with envy since encountering Home to Barcelona some years ago, for it is the great, comic novel about English teaching I tried and failed to write. In 1980s and '90s Barcelona, the bosses of crummy language schools ripped off the teachers and the teachers defrauded the students. All a potential owner needed to do was rent a flat, buy a few chairs and tables and hustle flyers round the neighbourhood. If you could persuade the students to pay a term in advance before they found out how crap the “teachers” were, even better.

Teachers? No problem. A gaggle would be knocking on the door every September for jobs without contracts or social security. Most teachers know nothing about education, but happen to have been born in a country where English is the main language. I know, because I was one of them. For many years, we organised within Comissions Obreres a section for language school workers. Trade union organisation was an uphill battle. The “Expatriate Manifesto” in Home to Barcelona catches the mood: “We are not morning people. We are not athletic, though rarely are we fat. We have above average intelligence, but are chronic underachievers… We often have a special relationship with alcohol.”

Ferry is easy-going, ingenuous, the innocent abroad. He knows no Spanish or Catalan and hangs out with other “English teachers” in Irish pubs. He starts waking up in strange places, covered in shit, after alcoholic black-outs. He has fled a conventional future and lousy job in California for a life out of control and a lousy job in Barcelona.

Home to Barcelona has countless anecdotes and cameos. Here's one: Ferry meets Martin, a smooth Belgian who gives him advice on how to develop a sex life. Easy, just find a woman reading alone on the beach and start chatting. Ferry tries. He feels too white and podgy to take his clothes off. Sweating, he sits down on the sand next to two oil-glistening topless bathers. “Have you got the time?” he asks, his voice coming out too loud. He realises he's wearing a watch. He looks round at a male bather staring at him and jabs manically at his wrist. “Roto,” he shouts. The young women are already packing up. It's a very funny scene, much funnier in the original than in my summary. It is, too, a poignant, melancholic moment. Ferry is not ill-intentioned; he's even likeable. But he is inept.

If you can't sort out what to do with your life, you can go anywhere and teach. The people you meet are like Kylie (from Sydney, with “dirty, blonde hair”), Clarence (American psychopath) or Gordon (acned Englishman “with a wry smile screwed on to his face”). Then there is Wichitom, the 60 year-old fantasist who's lived a life in teaching, touring the world's cities. Richard Manchester pinpoints many English teachers' attitudes: hating the job, critical of Catalonia, contemptuous of their students, loving to show off newly acquired local knowledge. Several comic riffs deal with the reality of getting through classes with a hangover and no material prepared.

Hello Its English Time!

The author is, of course, much subtler than Ferry, his first-person narrator. The writing is pleasurably vivid, with sharp descriptions of the city's contrasts and tone-perfect dialogue that catches the lost foreigners' inanity, aggression and loneliness. The book appears to ramble through anecdotes, but its structure is tighter than at first appears. Ferry's California family is present in the background throughout and the end of his story (involving inevitably bottles of alcohol in the small hours) packs a powerful punch.

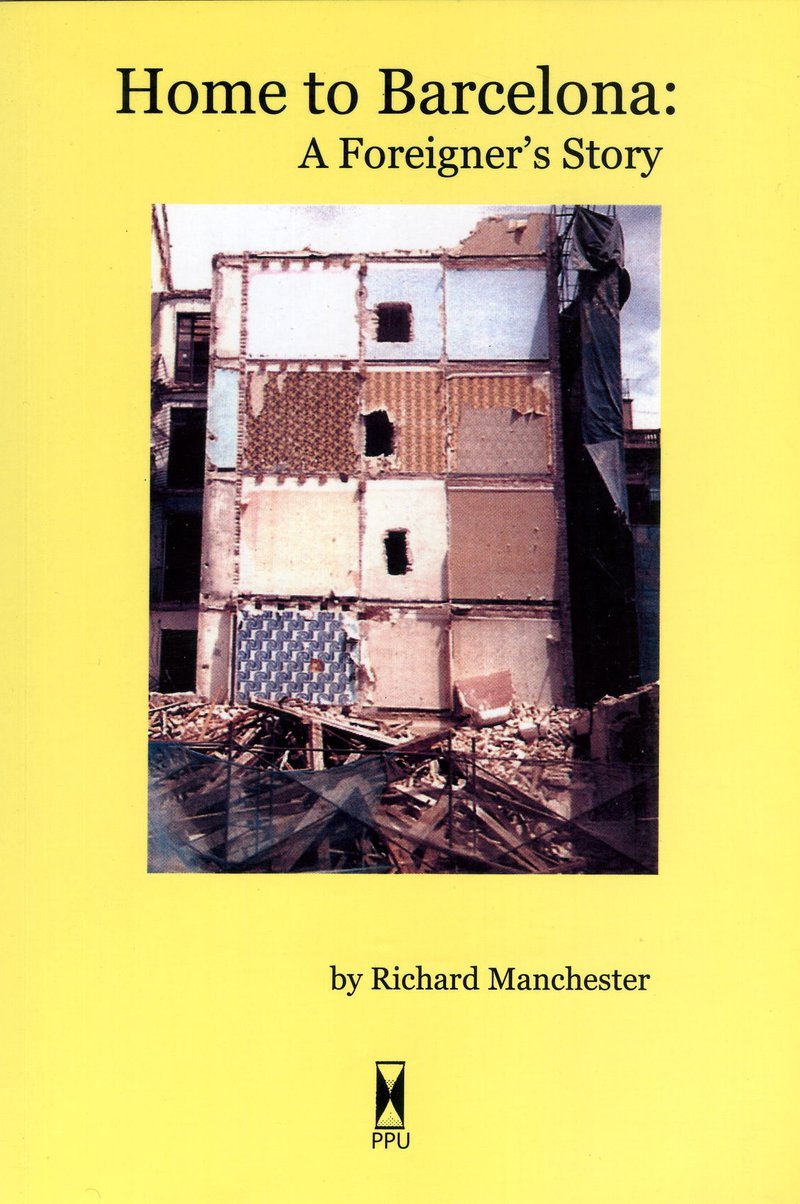

Catalans are satirised, sometimes with terrible clichéd ‘jokes', but his main targets are the ghastly teachers. The humour is often adolescent; the characters, always self-indulgent. His jokes about language are painful and sometimes painfully good. It's a book with added value: drawings and photos are scattered throughout. Surreal cartoons parody the Headstrong books (sound familiar?) used at the Hello Its English Time! (sic) school. Photos of beer lorries, demolition and slums (Ferry's determined to avoid seeing any tourist sites) accompany Ferry's journey to the end of the night.

Did someone say Barcelona was glamorous? Kylie tells Ferry the score: “We're here because of fear, resentment, pathological unhappiness. We say opportunities, education, experience — but everyone is here because something where we were went broken.”

Kylie's grammar's a bit off, but the message is clear. Life's a comedy with a tragic ending, say the philosophers. For Richard Manchester's “teachers”, English teaching in Barcelona is a comedy that ends in sacking, illness or depression. Ferry and his colleagues want to escape their lives and reinvent themselves on the shores of the beautiful Mediterranean. But their lives accompany them.

* Correction: In July's issue, my mind slipped sideways and I announced this title as Homage to Barcelona, which is in fact Colm Tóibín's non-fiction book about his discovery of the city

The Satirist

Richard Manchester spent two years teaching English in Barcelona. While there, he published a satirical review on expatriate life, The Advocate – like Sic, the magazine in his novel. Now he lives and teaches writing and literature in Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

On-line, there is a grainy photo of the author behind a balloon-glass of white wine at the bottom of an extract from Home to Barcelona published in the Barcelona Review in 2002. This is the only other photo and publication by Richard Manchester I have come across.

You can learn as little as I know about him and find out where to buy this inventive and imaginative book by visiting www.richmanchester.com