Lost grandeur

An American art collector ponders the lost treasures of the ill-fated and ruinous monastery of Poblet

Women Travellers in Catalan Lands

And if the church of Poblet contains only the mutilated reredos and Royal tombs, the other apartments contain even less—stripped, dismantled to the uttermost trifle that was not an integral part of the very walls themselves. Perhaps the greatest loss to Catalonia, for she is still very rich in art, was the magnificent library which the Viceroy of Naples, Don Pedro of Aragon, presented about 1670. The three thousand seven hundred volumes, containing many gems of early engraving, were uniformly bound in red leather, with the Royal arms on each title page.

With this much to guide him, the learned bibliophile, Mossén Jaume Bofarull, canon of Tarragona Cathedral and curator of its Episcopal Museum, is trying to trace the dispersed library and compile for it a posthumous, as it were, catalogue. Collectors throughout Catalonia who possess Don Pedro's volumes have, with few exceptions, cooperated by sending, or permitting to be made, facsimiles of the title pages, but the units that got into English hands, and thence into American, are proving a stumbling-block. [...]

Don Pedro's gift represented only a portion of Poblet's literary hoard. Its own library, formed long before, and its own precious manuscripts and early illuminated books, were in themselves of enormous value. As these bore no special mark of identification they could never be traced even were there no end of ardent Bofarulls available for the task. What were not purloined were carried off to the Archivo Nacional of Madrid where, it is said by the unforgiving Catalans, they still lie unsorted and uncatalogued.

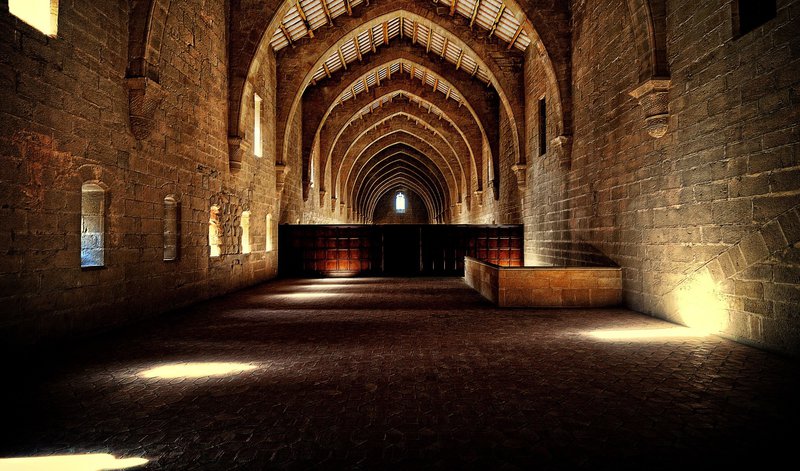

From the stark naked stone library one wanders on through innumerable other apartments equally denuded—refectory, dormitories, store-houses, chapter-house, wine-presses, infirmary, barber shop or calefactorio, bakery etc.; for the Poblet monastery was a veritable town containing within its own precinct all the offices, habitations, and workshops that would make it unnecessary for its inmates to go beyond the walls. [...] The most impressive piece of the great ensemble is, after the church, the novices' dormitory. One hardly likes to summon up the vision of some hundreds of lusty young frailes snoring there in concert with not a screen between for modesty's sake, but that picture intrudes for only a moment; the permanent impression is of the hall itself, a noble vista of twenty bays separated by broad stone arches thrown across and succeeding each other in never-ending line. Surely they once upheld a decorated wooden ceiling like the one in the royal chapel of Santa Agueda in Barcelona, for that was the typical Catalan combination with lateral stone arches. […]

We have said that Don Martin the king never lived to occupy the royal palace overlooking the cloister. With his death (1410) misfortune unremitting settled on his chief realm of Cataluña; for he left no heir, and through the influence of Saint Vincent Ferrer of Valencia, acting for the pope, a Castilian prince, Fernando of Antequera, was nominated to the throne of Aragon. That bleak kingdom, it must be remembered, would not have been worth his or Castile's scheming had it not included the rich coast provinces of Catalonia, Valencia, and the Balearic Isles. These represented the Côte d'Or for the arid inland region. Before the century was out, Fernando I of Aragon's descendant, Fernando II, had married Isabella, heiress of Castile. With the union of the two crowns the latter became the heart of the united kingdom and Catalonia sank into political insignificance. Isabella's passionate love for her own Castile was matched only by her disregard for her husband's domains; yet Catalonia was the goose that laid the golden egg, an ever present help when the royal exchequer was in a bad way. […]

When the time came to leave Poblet we were profoundly sad. The catastrophe had been so irrevocable. But as we walked back a wedding party driving to the station showered us with confetti and roused us out of a painful reverie. Here was careless, happy-go-lucky young Spain caring naught for past-and-gone art, and inviting us to be merry. At the station we went and shook hands with the bride, choosing a moment when the groomsman had left off tickling her with a feather and had turned his playful attentions to a bridesmaid.

Mildred Stapley Byne

The travels of Mildred Stapley Byne (1879-1941) are inextricably connected to the arts of old Spain. Born in Atlantic Highlands (New Jersey). In 1910 she married architect Arthur Byne (1884-1935) and they both travelled to Spain. It was the beginning of a long attachment with the country. Commissioned by the Hispanic Society of America, between 1915 and 1918 the Bynes undertook several photographic journeys across the Peninsula with a view to documenting its rich artistic heritage, often in a decrepit state. They took nearly 3,000 photos, culling a wealth of information that they subsequently used to jointly prepare influential monographs like Rejeria of the Spanish renaissance (1914), Spanish Ironwork (1915), Spanish Architecture of the Sixteenth Century (1917) and Decorated Wooden Ceilings in Spain (1920).Profiting from the collusion between unscrupulous aristocrats, clergy and local officials, through their legal antiquarian business they acquired and shipped to the United States hundreds of antiques, including dismantled monasteries, which were purchased by such moguls as William Randolph Hearst. The selected passage onPoblet from one of her books evinces her manifold artistic passions, which ranged from architecture and decorative arts to manuscripts and books, and regretfully records the irretrievable loss of a rich Catalan tradition here symbolised by Poblet's library, one of its most famed gems.