A revolution through poetry The doubting volunteer

The Spanish Civil War inspired many British writers. Last month's article looked at the heroines of Angela Jackson's novel Warm Earth. This month we return to the war, but to discuss hesitancy rather than heroism, in Stephen Spender's fine but simple poem, Port Bou

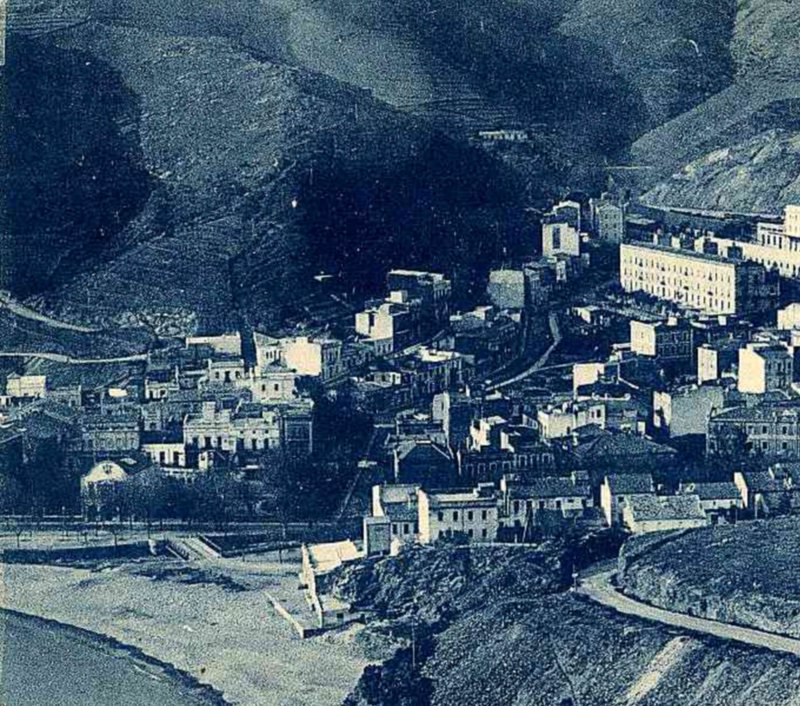

Portbou is a side-entrance into Spain, a forgotten border town of no more than 1,500 people huddled between the mountains and a small bay. Inland, scruffy Mediterranean pines are the only trees clinging to the steep slopes of scrub and shattered, black rock. Portbou is where the jagged end of the Pyrenees drops into the sea. Its beach is shingle and along the coast black cliffs rise straight up from tiny coves. Portbou is no resort. Here the Costa Brava really earns its name: the Rugged Coast.

The village covers the slope from the huge railway station, where decades ago the Paris-Barcelona passengers had to change trains, down to the bay. This ox horn-shaped natural harbour may give the town its name, bou in Catalan meaning ox, though the name may well be due to bou's other meaning: the technique of drag fishing with a wide, open net.

Smiling faces

Stephen Spender spent his first day in Catalonia at Port Bou, in February 1937, when he crossed the border, passing from peace to war. He had come to broadcast from Valencia in English, but despite his new and public membership of the Communist Party he was in private uncertain of what he was up to.

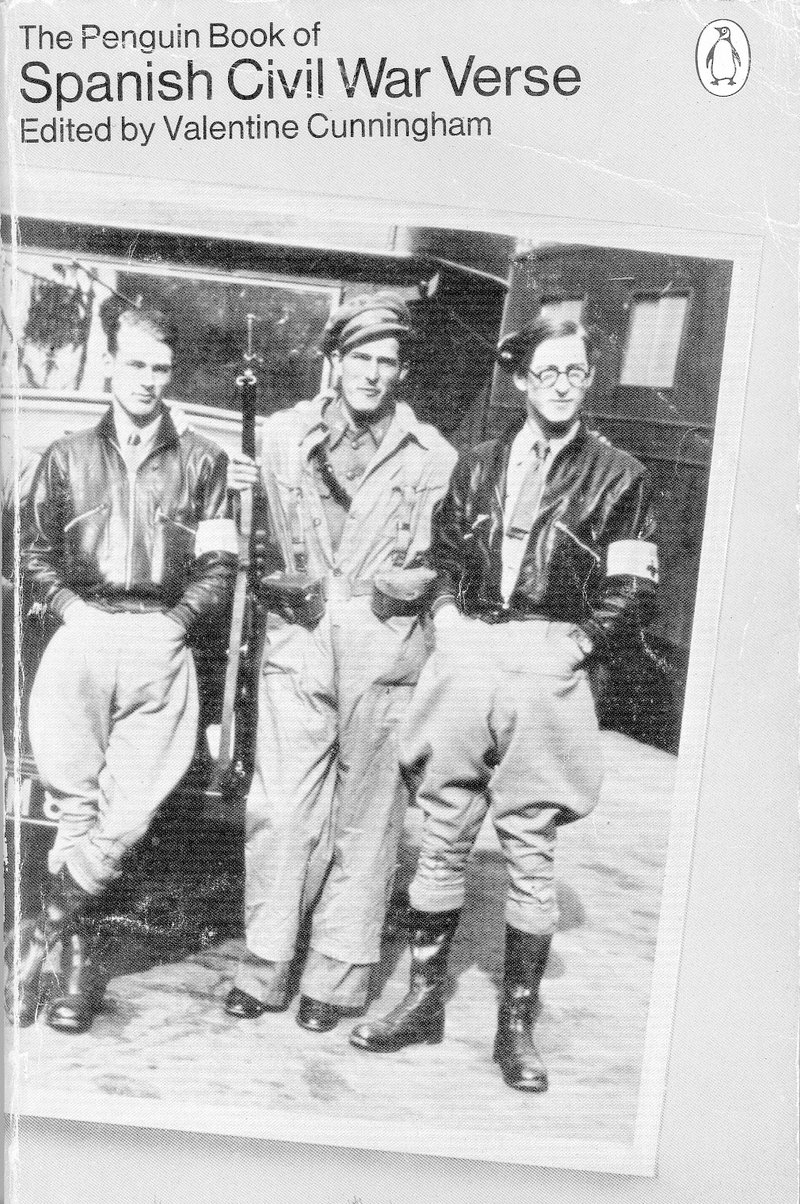

The Penguin Book of Spanish Civil War Verse, Valentine Cunningham's classic 1980 collection of English-language poetry about the 1936-39 war, has a section entitled Unheroic Notes. Here Spender has nine poems, far more than anyone else.

In his autobiographical World within World (1951) Spender recalls how he sat on the parapet above the pebble beach and answered —or failed to answer adequately, which is the theme of his poem— a lorry-load of militiamen, “smiling flag-like faces like one face” and eager for war news. His 48-line poem “Port Bou” describes how:

...the earth-and-rock arms of this small harbour / Embrace but do not encircle the sea / Which, through a gap, vibrates into the ocean, / Where dolphins swim and liners throb.

That is just what Portbou's natural bay looks like (though you'd be hard pushed to spot a liner). In the carefully structured poem, Spender makes the circling bay that does not quite close correspond to his “circling arms” around a newspaper and to his failure to connect with the militiamen who ask him for news, but are unable to read the French paper held out to them or to understand Spender's words.

The image of Spender and the smiling militiamen, still waving as the lorry jerks away, is reminiscent of another famous Civil War encounter. On the very first page of Homage to Catalonia (1938) George Orwell is deeply moved by an Italian militiaman he meets in the POUM's Lenin Barracks in Barcelona. The Italian gripped Orwell warmly by the hand, though neither spoke each other's language. Orwell wrote later, in 1943, of this as one of his two basic memories of the Civil War: “This man's face, which I saw only for a minute or two, remains with me as a sort of visual reminder of what the war was really about. He symbolizes for me the flower of the European working-class, harried by the police of all countries...”

Stitched intestines

These two Englishmen meeting militia on their first day in Catalonia are both honest in their very different ways. Whereas Orwell's powerful, romantic and revolutionary vision is expressed with a decisive handshake, Spender's doubt is reflected by his inability to connect with the militia. Orwell's description of the anarchist revolution of 1936 has associated Catalonia with revolutionary politics to this day, although the sympathies of most visitors are more likely to lie with Spender's ambivalent liberalism.

Indeed, Spender's many Civil War poems are interesting precisely because he was honest enough to express this ambivalence. Despite having just joined the Communist Party, he avoided Stalinist panegyrics about the working class. Spender felt that these poetic calls to arms often lured the idealistic young to their deaths.

Spender's intensely personal poem continues with the militiamen driving out to the Portbou headlands, where the circling arms of the bay nearly meet. They start target practice.

I assure myself the shooting is only for practice / But I am the coward of cowards. The machine-gun stitches / My intestines with a needle, back and forth; / The solitary, spasmodic, white puffs from the carbines / Draw fear in white threads back and forth through my body.

The machine-gun bullets close the circle. The connection made is not a frank handshake, but rather the fear of the lanky Englishman watching from the parapet above the beach. Spender was not a fighter writing about revolution, as Orwell was, or a soldier like Spender's admired Wilfrid Owen, but an observer of his own reactions.

This poem about doubt and cowardice seems brave today. In the middle of a war where a pose of public heroism was demanded, Spender remains in his poetry true to what he called his “divided heart”, giving an anti-heroic response to the Civil War.

Stephen Spender (1909-1995) was one of the best-known British poets of the 1930s, a leading member of a wide movement of writers struggling to create a new revolutionary literature that could contribute to the struggle against Franco's military revolt and the horrors of Nazism. In 1951, he wrote of the 1930s: “We were the Divided Generation of Hamlets who found the world out of joint and failed to set it right.”

He was one of the six contributors to The God that Failed, a 1949 collection of essays by ex-Communist writers criticising the Soviet Union and the Communism they had believed in. The book's very title shows that the six writers started from the false premise that Communist commitment was equivalent to religious belief. Nevertheless, the book became an intellectual weapon in the Cold War. Spender later became editor (1953-1966) of the influential magazine Encounter and always maintained he did not know that it was funded by the CIA.

In 1951, his fascinating autobiographical World within World explained his struggles to become a writer and the political-literary atmosphere of 1930s England. It described both Spender's development toward Communism and his intellectual and emotional life, including his bisexuality, though it only touched on his affairs with men: homosexuality was illegal at the time. In 1941 he married Natasha Litvin and they were together until his death.

In 1972, he co-founded the influential magazine Index on Censorship. Spender lived a long, privileged and influential life as a poet and critic. Long after his early socialism and doubts, he was knighted in 1983.